Working with rural communities in Karnataka, India, Decentralising Digital is an ongoing research project seeking to co-create new narratives for decentralised digital futures.

We are exploring how developments in emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things, the voice enabled Internet, machine learning and artificial intelligence might be harnessed to meaningfully support rural communities in India. We imagine that the work presented here can be adapted and used by other communities and stakeholders, in their own work in reimagining different, more sustainable futures for these communities.

We imagined a series of artefacts that might be found in these diverse futures. These artefacts intentionally adopt a visual and material language rooted in the knowledge of the people and the communities we worked with.

These futures mirror those we have seen emerging in India, where different people and communities play a part in engaging with decentralised technology in different ways. This is a future where people are not beholden to technology but choose to use it for their own good. A future where technology supports and complements existing sustainable patterns and behaviours, rather than imposing new ones.

The matter of how much technology we should include in these artefacts was debated thoroughly: we recognised that while some of these artefacts needed to highlight emergent digital technologies, it was also necessary to illustrate their plausibility within the contexts that enabled their adoption and success.

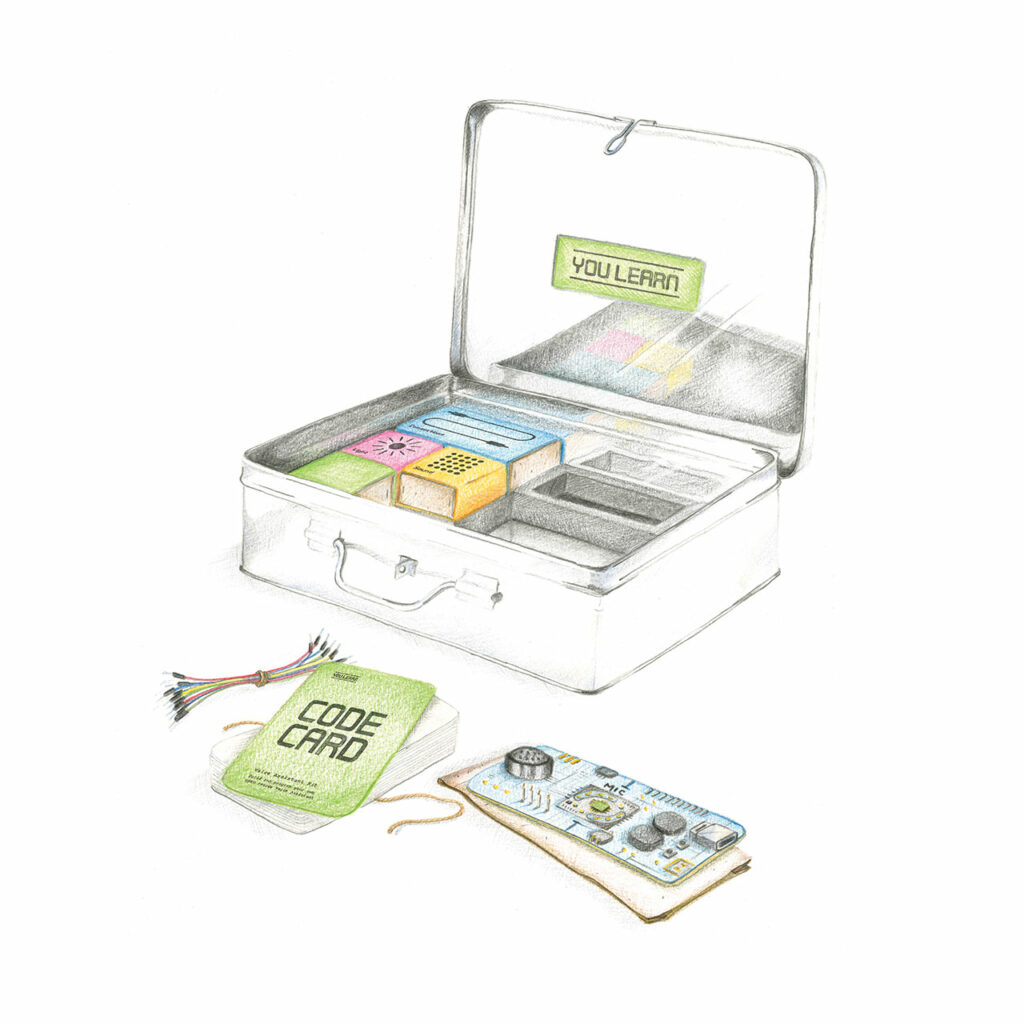

Children’s Coding Kit

Children’s Coding Kit. Stainless steel case containing ‘Your Voice’ developers board, various electronic components, and a deck of coding cards. 2025.

Education builds hope. Hope that can help challenge an overtly globalised society in which the centralisation of technology has stifled local innovation and resulted in the uneven distribution of wealth. That the Soliga people possess such hope was evident in the way they worked with educators and technologists to develop locally-tuned digital products and services for themselves.

In 2025, a Soliga child studying at the Vivekananda Girijana Kalyana Kendra (VGKK) in BR hills signs up to participate in a government inter-school competition. The topic: designing hopeful technology futures for local contexts. A You-Learn coding kit arrives in the school’s mailroom. You-Learn advocates for fairer technology for all and seeks to help people understand and then take control of the algorithms and code that affect their lives. This simple metal box contains the building blocks of many futures. A Class 8 student takes the kit, cradling the box in her arms as she walks home.

Deepa’s parents are hovering over her. Just 12 years old,she is the youngest school lead in this inaugural You-Learn competition. She knows she’s smart. She’s always been that. Her parents watch with expectation and trepidation as she opens the shiny metal box. Inside is the world’s first microcomputer that can be programmed by speech. In Deepa’s hands, it will become the world’s first Soliga voice assistant. Deepa was part of the first group that helped user-test the alpha release nearly two years ago. Working with a young Soliga researcher, Dr. Nagamma C,she and the team tested the technology to see if it could help catalogue and preserve the sounds of the forest. Now, she has two weeks to lead the team that will build a prototype voice assistant, one that will be tested directly by the tribe’s elders. A voice assistant that can be sung to.

Deepa finishes unboxing the microcomputer, plugs it in, and says what she has been waiting two years to say: “Hi Soli, can we get started?” Tiny lights on the circuit board flicker like fireflies in spring as a Soliga voice says *Opening file: Hello BR Hills. Adjusting mic-array to 80cm. Calibrating for female voice. Hello Deepa, what do you want to do?*

Soliga Voice Assistants

Three Soliga Voice Assistants. Turned painted lacquered wood, brass bezel, various electronic components. 2034. Cast bell metal, metal bezel, woven twine, various electronic components. 2045. Perforated dried gourd, brass dial, woven twine, various electronic components. 2030.

The emergence of open Voice AI means that people are free to create their own voice assistants, naming and interacting with them however they like. In time, these AI devices become less like assistants and more like pets; cared for, taught, and nurtured over many years. Their forms are crafted by local artisans and individualised to their users. With their early commitment to teach coding in tribal schools, the Soligas are now at the forefront of new experiments to decentralise technology in Karnataka. The AI device has been taught that Soliga voices are an indivisible part of the forest’s soundscape; that they are as much part of the forest’s sound as the woodpecker’s tap and the wolf’s howl. Languages and sounds are encoded in ways that respect the Soliga culture and lifestyle. Bird calls, the swish of the wind through the leaves, and the humming of bees are all part of the vocabulary of an AI trained for and by Soligas. A voice assistant for the forest.

The group of four Soligas has paused for rest under the Dodda Sampige Mara. A young man and woman are inspecting the markings on a hollowed-out gourd while the other two are resting their backs against the broad tree, the spring sunshine playing on their closed eyes. “No, that’s not how you do it,” says the woman, “give it to me”. She takes the device from the man and holds it confidently, adjusting the dial at its neck while listening attentively to the quiet clicks of the device. “You need to focus the distance first like this, and then…” she stops turning the dial and points the device in the direction of a far-off whistling sound. *Black Drongo food call signifying presence of bees* says the device in a sing-song Soliga voice. “Easy as that – if you’d learnt from Achugegowda, you wouldn’t be needing this anyway” she scolds in a friendly way. “Yes, but you made it – of course it’s easy for you to use, Deepa” the younger man flashes. “Pah, let’s go. We need to bring home that honey, come on you two”.

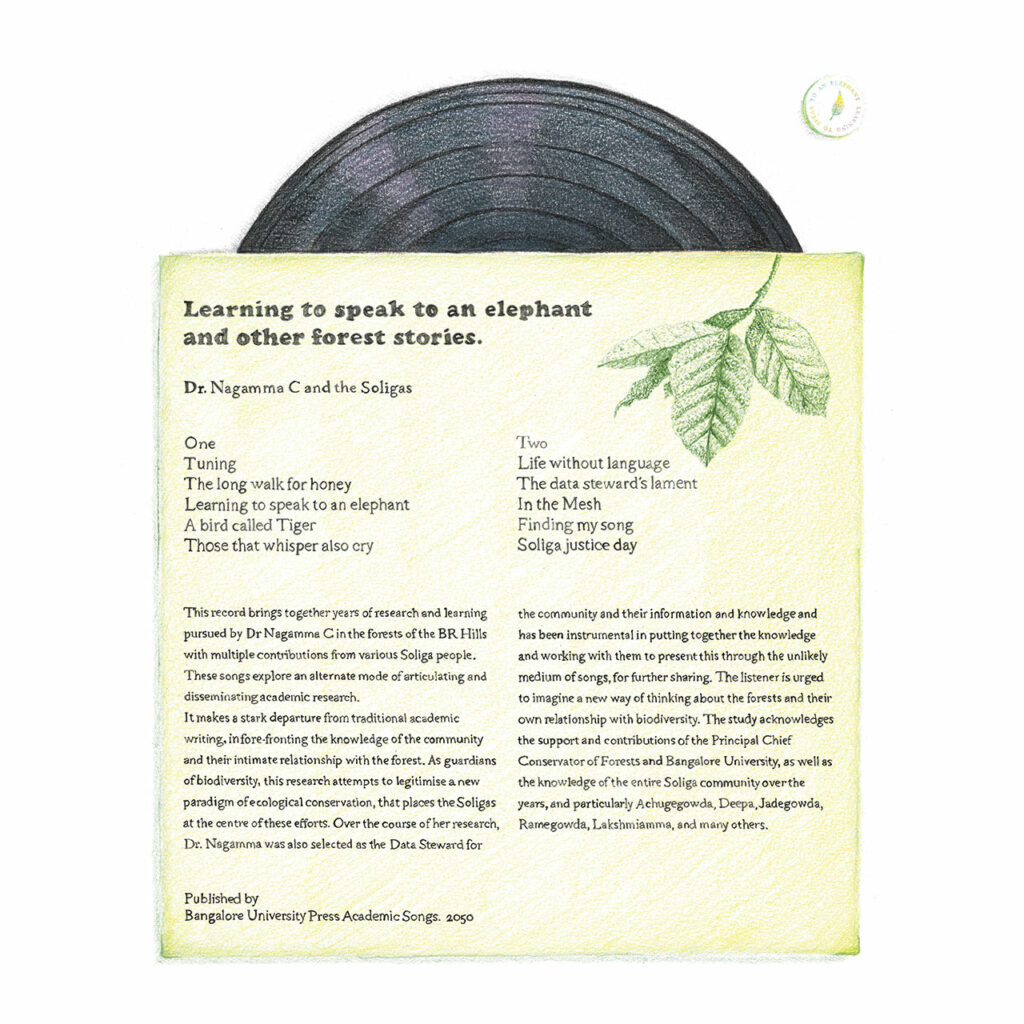

Learning to speak to an elephant and other forest stories

Learning to speak to an elephant and other forest stories. Vinyl record published by Bangalore University Press Academic Songs. 2050. Laser written, nanostructured glass, 5D optical data disc. 2050.

The increasing integration of technology into tribal life creates the need for new approaches and practices, particularly around the governance of the data it records and generates. One such approach is the development of Data Stewards, people elected by the tribe to oversee the data, its collection, its use, and how it is shared.

Backstage, Nagamma is unconsciously playing with the small glass disc in her left hand. It still feels strangely like a toy. She can hear the announcement starting out front. The host of the 25th anniversary Data Handlers conference is introducing heras this year’s keynote speaker. Nagamma hates this bit. “Oh my,” she thinks. “I’ve been doing this for too long”. She wonders if they will have grown tired of the story of her transformation from a Soliga language denier to its champion? Or the part where she reflects on writing papers about the forest in Kannada and English before gaining the confidence to return to and embrace her native tongue and mould it into a language fit for academic discourse? Will her transformation from writer to singer still resonate with this young audience?

On stage, she can hear the host telling the audience how Dr. Nagamma C changed the world’s view on data belonging to the forest; how her initiative of ‘designing for life’ meant the end of data as something remote from the people and place; that data, places, the forest and its life had all to be treated as a ‘single entity’. She hears her describe the early work, and shudders at the idea that she ever had to write papers … that seminal paper on Ways of Seeing should really have been a seminal song.

Despite nerves, she feels her excitement building and allows herself to feel just a little proud. She is holding two discs. In her right hand is her first vinyl record, released by Roopa’s Socio- biodiversity department at Bangalore University. She knows the vinyl is an affectation but she can’t help but be excited by the idea of listening to her songs and field recordings on a turntable, the sounds representing the heart of her people and the forest. In her left hand is a glass disc the size of the now-defunct two- rupee coin. This, she told Roopa, was her life’s work, a 5D optical data-disc that contains everything she has ever recorded in BR Hills. The disc can survive for millions of years.

She waits for the host to stop. She then takes a deep breath and walks to the centre of the stage. She looks out at the audience, smiles widely and opens in her usual way:“I’d like to sing you a story”.

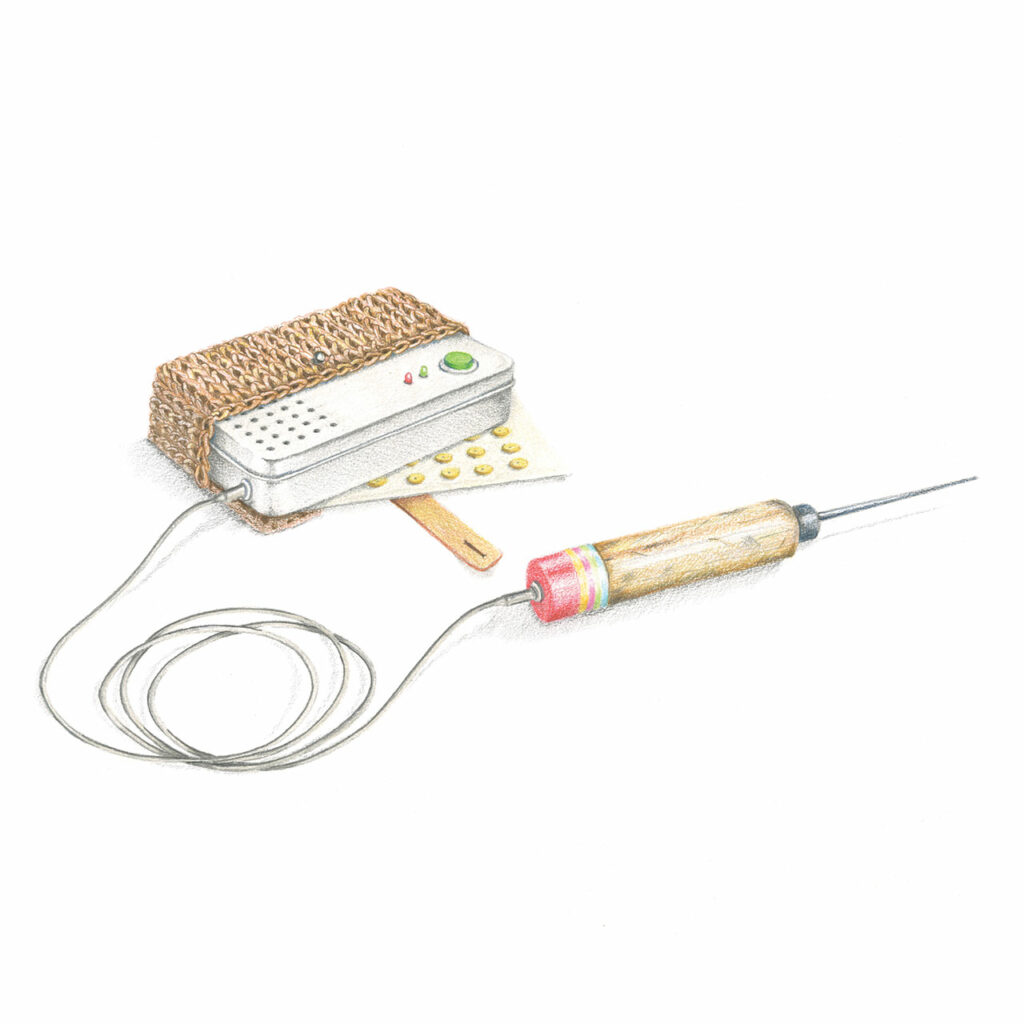

Mesh Hotspot & Instructions

Mesh Hotspot & Instructions. Make Your Own Hotspot instructions by the Meshmaker organisation. 2025. Mesh Hotspot from Gulbarga Colony, Bangalore. Plastic Bottle, wound wire aerial, solar panel, various electronic components. 2038.

Mesh networks offer a different way to access information and services from the Internet. The circuitry, tools, and instructions to add a new mesh hotspot or node to a network in a village are decentralised. The code and protocols for adding a node to the network are open-source and can be shared through text messages, SD cards, or written instructions. Taking these open protocols and hosting them on a piece of hardware is typically completed in rural hack labs. These are then shared with the local community so they can host nodes in their homes, shops, and businesses.

It is in one of these rural hack labs in 2025 that a simple set of instructions is written to help communities set up hotspots for the first time. While the principles underpinning the code and hardware are relatively consistent, the material and skills available to house the technology are different in each village. A vernacular technology is created, with the design and build of each hotspot reflecting its geography and culture.

Dinesh and Vidya are working late, putting the final touches to the first edition of their ‘Make Your Own Hotspot’ guide. Dinesh looks across the table to Vidya.

“What’s troubling you?”

“I’m still figuring out how best to edit this so that there’s focus on the local design aspect”.

“Let me look at it”. Dinesh sits on the opposite side of the table and takes a pencil and notebook out of his shirt pocket. He pulls up his bifocals from around his neck and, brow furrowed, looks at what Vidya’s handed him.

“I think it looks fine, Vidya.” He removes his glasses and continues. “What’s important is for these communities to see that it is enough if the hotspots are compatible; that they don’t need to be alike. As long as they are able to talk to each other, they can take on any form and be made with anything, whether it’s the jondu grass and bamboo we have here at Iruway Farm or reuse the waste plastic of the city!”

Vidya laughs, “Do you think cities will ever want to make mesh hotspots?”

“I don’t know” replies Dinesh, “It would certainly be novel for the cities to learn something from us ‘villagers’, but I’m hopeful, Vidya, I’m hopeful.”

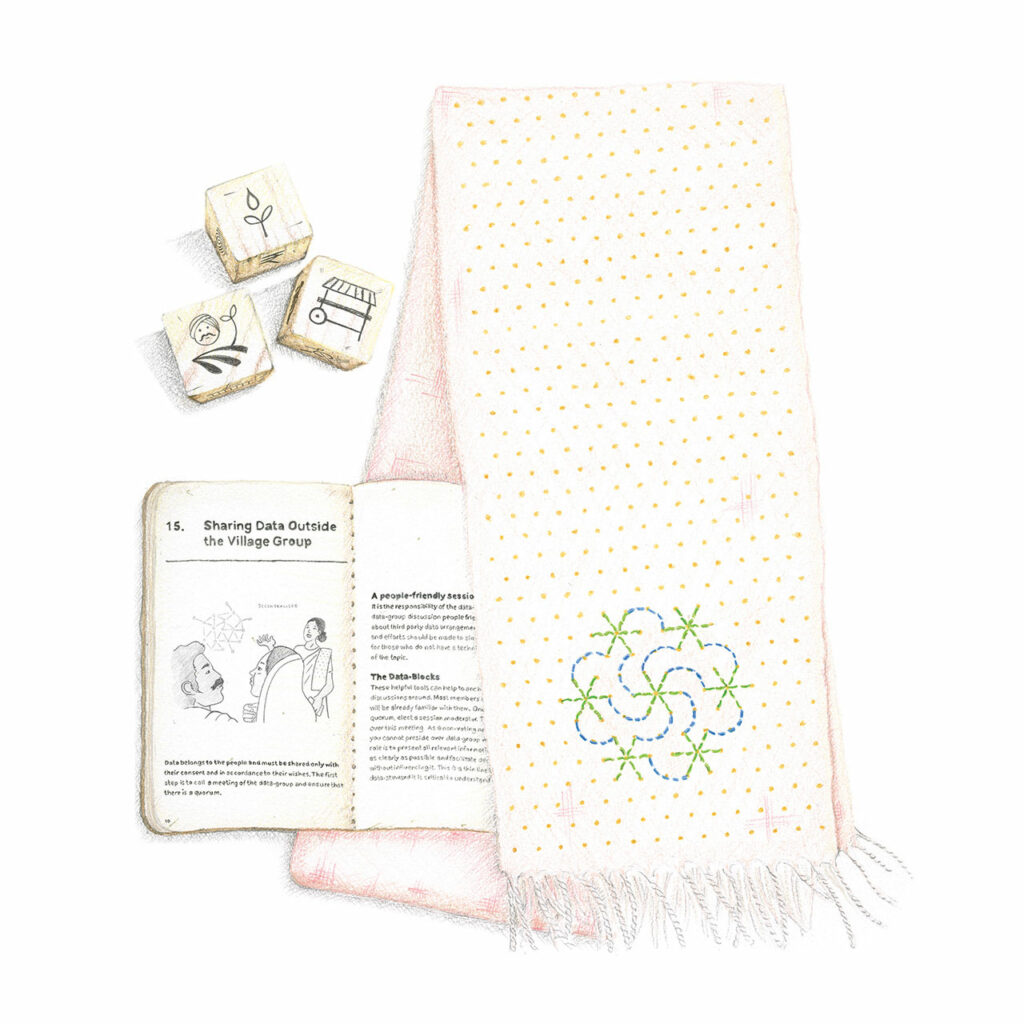

Data Steward Scarf, Handbook & Data Blocks

Data Steward Scarf, Handbook & Data Blocks. Data Steward Scarf. Khadi Cotton, block printed and hand embroidered. 2032. Data Steward Handbook. Softcover booklet. 2032. Three Data Steward Data Blocks. Screen printed, wooden blocks. 2032.

The proliferation of decentralised technologies in rural areas of Karnataka demands a new approach to managing data in ways that are sensitive to and respectful of the local tradition and culture.

Jayalakshmi is sitting on her bed and holding up her just- awarded Data Steward Scarf to her face. It feels so official and important and the fact that it was made locally (using the practices and crafts of her community) makes her doubly happy. Tomorrow she will wear this as she does her first data-walk around Durgadahalli. She is gripping her handbook tightly; its worn edges and scuffed front speak to the many hours she’s spent reading it. Of course she knows every word – she scored 100% in the test last week – but knowing something and understanding something are not the same. She knows everything in the book, but will she know how to explain to Gopi how he can ensure his bee-sound-capturing files are kept anonymous? Will he understand when she explains to him that shouting about how ‘Lakshmi’s honey is the best this side of the forest’ means the data is no longer anonymous?

Maybe she can use the Data Blocks to discuss different approaches to data collection and privacy; who knows, together they might come up with a better approach! She knows the kids at school will have everything right, but will they be able to rate the value of the butterfly counts they have been doing on their way to the school? Will they be able to score it as highly as they should? Will they know that the presence of a swarm of butterflies can, when fed into a You-Learn rain predictor, be used to predict the start of this year’s rainy season? Will they know how to normalise the data they’ve collected given the relatively large size of their school? So much to do in one day. Her first day as Durgadahalli’s Data Steward.

Mesh Bowl and Data Tokens

Mesh Bowl and Data Tokens. Mesh Bowl. Turned, oiled wood, various electronic components. 2045. Five Data Tokens. Turned, lacquered wood, various electronic components. 2045. Mesh Mat. Khadi Cotton with hand embroidered detail. 2045.

As the mesh expanded across India it created a new network; an Internet that could be transmitted from house-to-house and across villages, towns, and cities in a radically decentralised way, each iteration reflecting local needs and benefitting from diverse knowledge. The mesh placed privacy controls in the hands of everyone in a transparent manner with people and households given agency to steward their own data.

As the network grew in Karnataka, a partnership sprang up between the lacquered wood-toy-making village of Channapatna and rural hack labs. They collaborated to make bowls and tokens that people could use to create glanceable interfaces to control the privacy of different types of data on their home’s mesh network.

The ‘Mesh Bowl’ acts as a node within a broader mesh network. It also gives people the ability to control the data that flows from their devices through the Mesh. The five tokens represent five different types of data; Aadhar, Text, Camera, Location, and Sound. A token inside the wooden dish indicates that the data type is private. Moving the token to the fabric mat changes it into a transferable data type. As new forms of data are recognised, new tokens can be added to control them. Beyond Karnataka, different areas are developing their own tokens – often drawing from local craft cultures, privacy customs and behaviours peculiar to the people of the area.

“Tanveer! Stop messing with the mesh… I need photos. Put it back. Give me back my photos.”

“I need privacy. You don’t need the photos”.

“Muuuuum.”

Tanveer lets the brightly coloured token fall into the Mesh bowl just as his mum enters the room.

“Tanveer, the Mesh is for the whole family. Your sister wants to send her friends photos of her project. We can turn photos off when she’s finished”. Tanveer is clearly disgruntled. Last Tuesday, one of the founders of data stewardship, Jayalakshmi K, had come to visit his school and given the best talk he had ever heard. Privacy, she had said, was a basic need in the same manner that water was but it also had to be constantly cared for and managed within homes and villages. He had heard of an update to the Mesh Tokens that would allow one to exclude photos of specific people. He could hardly wait for that update! He could then glue its token into the mesh bowl and protect himself from his sister’s constantly clicking camera. Until then, he would continue to take the Photo token out anytime he could.

Slow Story Food Packaging

FarmLab Seeds. Three packets of heritage seeds for bespoke companion planting. 2035.

The emergence of narrational AI and open source voice assistants connects consumers to farmers in new ways. The prevalence of open source You-Learn kits and the trend towards digital jugaad amongst farmers has made hyperlocal data collection on Karnataka’s small holdings and farms commonplace, but it is the combination of this with Slow-AIs that has really helped farmers.

Vishala of the ‘Buffalo Back Collective’ was instrumental in working with developers to transform this technology into one that worked for busy farmers who wished to to tell their story to their customers– the results of these collaborations were Slow-AIs, that gradually track the growth of crops. Using data from DIY farm tools and with the ability to capture and translate local dialects, these AIs take snapshots and moments from everyday farm life and convert them into stories and insights about crops and the people who grow them.

At food markets across Karnataka, farmers now wrap their produce in on-demand printed paper bags that provide consumers with context and information about their hyperlocal purchases. These Slow-AI stories, combine farmers’ tales, recipes, and advice with data from FarmLab kits such as weather and soil quality.

In his farm, Narasimha sits under the banyan tree that borders the village. The rains have cleared and the air is cool. August is his favourite month. He can see the ragi millets pushing their way through the red soil. They are robust plants that thrive on just the regular monsoon rains. Nowadays, they are also so much tastier than they used to be when he was a child; and though these won’t be ready to harvest until October, Usha is already out on her bicycle with its attached camera-kit, photographing both the still-wet soil and him under the tree! What had she said? … “It’s how we tell our story, Appa”. In a few days, his picture will likely show up on a paper bag full of ragi somewhere in Bangalore.

“Every bag will be unique” she’d said and, apparently, according to Usha, people will collect these packets and see what life – their life – on the farm looks like. Narasimha chuckles to himself – his father would have scoffed at the notion, but Usha’s idea has been working. By telling their stories, they have increased sales and are able to charge a fair price for their hard work … or, rather, Usha’s hard work. They now have regular sales across the city and even visits from city folks. Before the rains started, a group had arrived for a tour in an air-conditioned 4×4; each one clutching paper bags with pictures of Narasimha’s okra crop. They had left with boxes full of tomatoes, end-of-season-mangoes, and peas. City folk here – another thing his father would have laughed at.

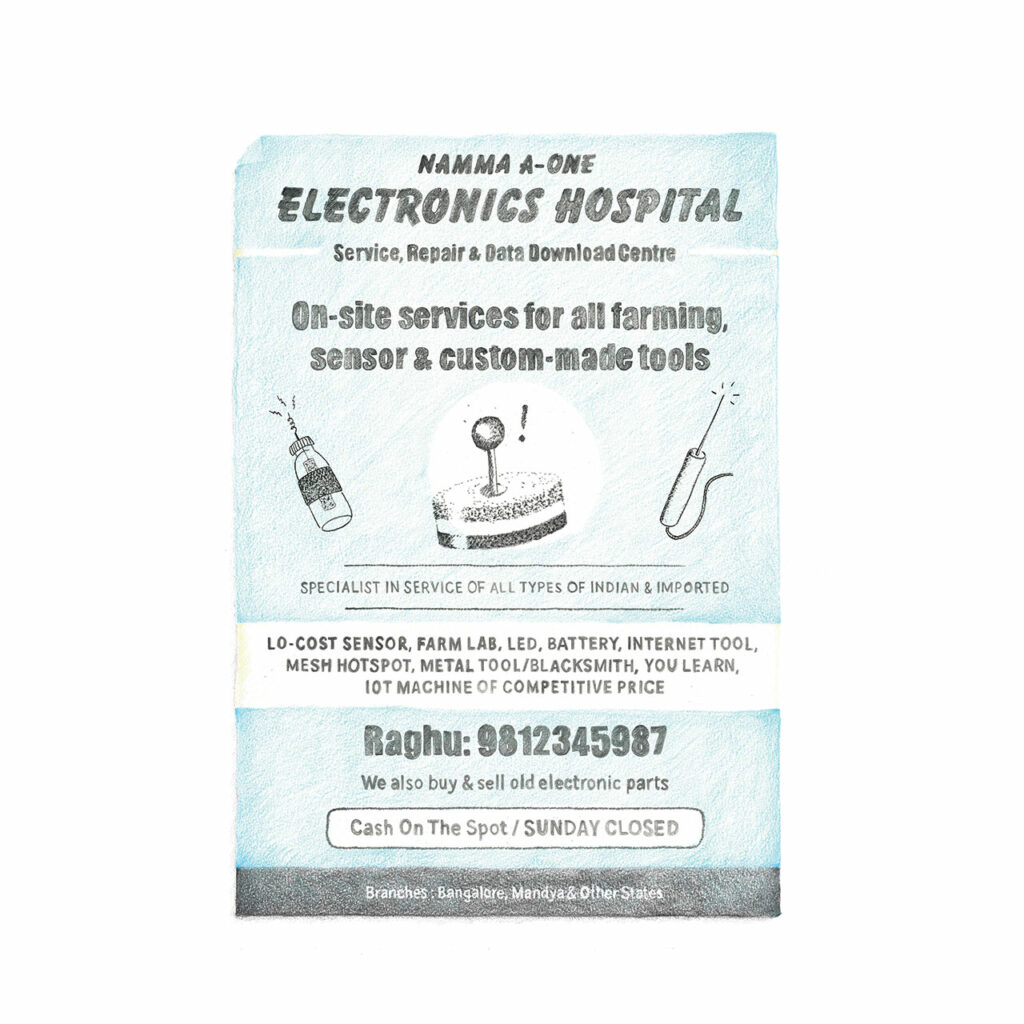

Electronics Hospital Flyer

Electronics Hospital Flyer. Paper advertisement for Namma A-One Electronics Hospital. 2040.

With India enthralled by an emergent digital swadeshi movement, the decolonisation of the Internet, and the decentralisation of networks, we have started to see new kinds of repair shops that embrace what many are calling digital jugaad. ‘Repair, mend, and restart’ is now for people’s Internet-connected devices what it once was for bicycles and farm tools. New regulations control India’s right-to-repair and holds for all domestically-manufactured goods, including the Internet of Things. This, combined with a nationwide training program in creative technology from You- Learn, has led to an explosion of micro-workshops across cities, neighbourhoods, and villages, geared towards repairing and repurposing everything from fitness trackers and voice assistants to GPS seed planters and mesh controllers.

Usha leans her bike against the front of ‘Namma A-One Electronics Hospital’. The hospital is a small three-by-three metre shopfront, housed within a two-story building that runs along the main street. It is part shop, part workshop, part school. The window is packed with boxes, old and new, containing home and farm electronics: pick and mix data tokens from Channapatna, an 8th gen GPS seed planter, a You-Learn water pump adapter, an aged weather-trowel, and a host of regular tools that have been rigged- up to include all sorts of AI-powered sensors. Shalini, who set up and ran the electronics hospital, is as much a part of the DNA of this building as the bits flying through the mesh network. The shop manager now, she is a local legend and regular data offerings are left outside her shop and on the mesh. Usha is here to attend one of Shalini’s You-Learn workshops. This one is about microbial- soil-matter upgrades for farm tools. Usha is happy to take off her heavy backpack and unpack the ten soil sensors she is upgrading for her village. She’d received a message from Shalini a couple of days ago: You-Learn’s neural networks were now ready to resolve a new set of identification metrics for microbial measurement. Managing the upgrade was not beyond Shalini’s capability, but it was complex enough that Shalini was worried about not having the time and resources to upgrade everything individually. Usha had happily agreed to assist; she knew too that looking after her soil sensors was just like looking after her crops. It was something her dad had taught her when he was still alive: if she treated her crops well and gave them the care they needed, she’d be able to look forward to a healthy harvest.

More artefacts

About

These artefacts are part of Decentralising Digital, an ongoing research project seeking to co-create new narratives for decentralised digital futures working with rural communities in Karnataka, India. The research is led by Quicksand, an interdisciplinary design research and innovation consultancy based in India, and in collaboration with local community partners, creatives from across the country and designers from the University of Dundee, UK. The team includes Loraine Clarke, Babitha George, Romit Raj, Jon Rogers, Neha Singh, Martin Skelly and Pete Thomas.