As websites grow larger and add new features – such as AI-powered assistive agents, rich media, and complex scripts – the carbon footprint of web browsing is increasing steadily. Where the world’s first websites were plain HTML, with a total page weight in the scale of kilobytes, modern pages often exceed several megabytes. As the internet has expanded, the energy used in sustaining its networking and computational needs has also grown. The environmental cost of this upwards trend cannot be understated: The internet accounts for 3.7% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and some predict that percentage to increase to 14% by 2030.

Yet, website developers do not have to be powerless bystanders in this process – organizations such as the Green Web Foundation and Wholegrain Digital have created guidelines creators can follow to reduce the carbon footprint of their sites.

Aesthetic trade-offs vs. user experience

Among Wholegrain Digital’s recommendations for a greener internet are ones that would alter the aesthetics, and thus the user experience, of a website. These aesthetic changes include: ‘reduce images’, ‘reduce video’, and ‘choose fonts carefully’. Implementing these changes involves reducing the resolution of media, converting videos/images to grayscale, disabling autoplay, removing font files, and more.

These tweaks are difficult to realize without understanding their impact on the user experience (UX). If a website’s aesthetics are damaged by sustainable design alterations, what motivates developers to implement them?

To bridge this gap, we may need a new UX design metric that factors in how users feel interacting with a website, alongside its usability and entertainment value. Just as the true cost of driving a car extends beyond time and money, the total impact of visiting a website stretches beyond the immediate reward of entertainment.

User study: Balancing emissions and aesthetics

To understand the tradeoff between traditional UX and carbon reductions, we designed a user study to answer two primary questions:

- How does a user’s preferences in website design change (if at all) if they know relevant emissions information?

- Which specific changes do users tolerate best when given the opportunity to design a greener internet?

We conducted the study using Harvey Mudd’s media-rich website – Harvey Mudd is a small liberal arts college focused on providing a humanities-centric STEM education. Their site features a large autoplaying video, news blurbs, and graphics displaying the college’s relevant statistics and awards. The website earned a poor score of F under the Sustainable Web Design Model’s rating system, giving us plenty of room to improve its carbon footprint.

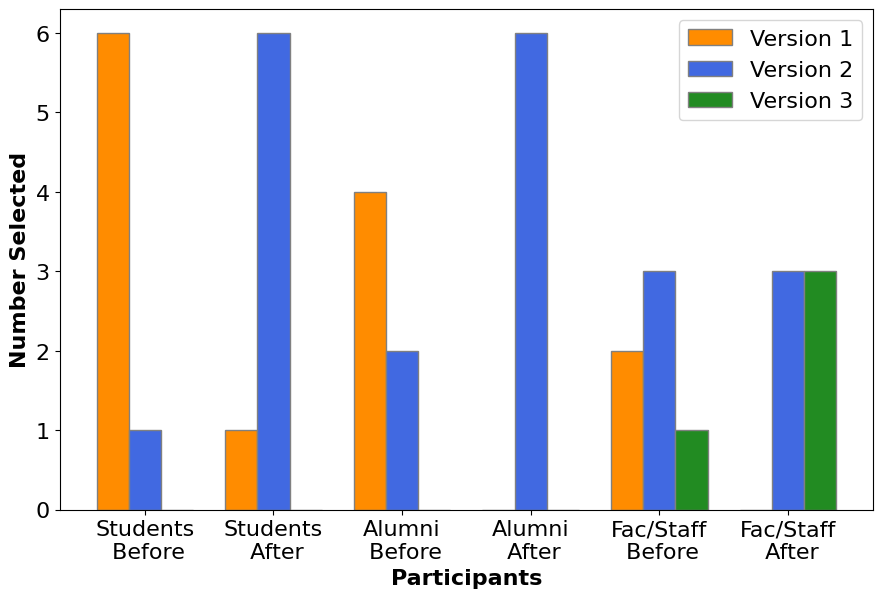

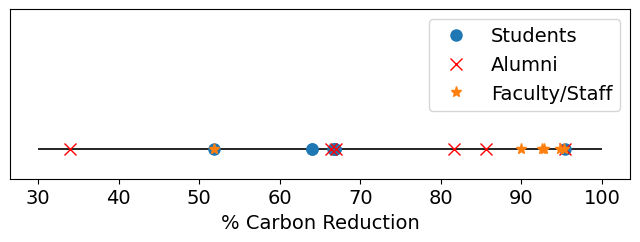

While choosing participants to interview, we aimed to capture groups that have different relationships with the website: 7 current students, 6 faculty/staff, and 6 alumni (all of whom graduated within the last 10 years). Our study was granted Internal Review Board (IRB) exemption status by Harvey Mudd’s review board.

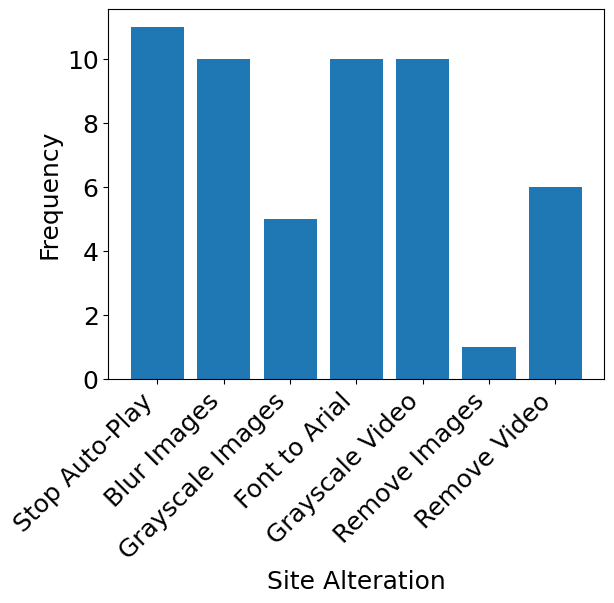

The study had two main components, designed to answer our two core questions. In phase 1, users choose between three variants of the website (the original, a moderately stripped, and a bare-bones version), both before and after learning about each version’s emissions. In phase 2, users customized the site – for example, disabling auto-play, blurring images, and altering the font – and watched the resulting emissions drop in real-time.

After some trial and error, we designed our study around two Chrome Extensions that simulate green website alterations. The extensions interact with the website’s existing code, blocking/injecting altered images, videos, and fonts in response to the user’s selected settings. Using CO2.js (and the Sustainable Web Design version 3 estimation model), along with the Chrome DevTools and some crafty Python scripting, we calculated the carbon reductions corresponding to each website alteration (see table below).

| Alteration | Website Size (MB) | Emissions (gCO2e) |

| Control | 77.02 | 27.89 |

| Delete Video | 5.7 | 2.06 |

| Delete Images | 74.02 | 26.80 |

| Disable Autoplay | 39.26 | 14.21 |

| Blur Images | 75 | 27.145 |

| Gray Images | 75.38 | 27.289 |

| Gray Video | 49.3 | 17.85 |

| Front to Arial | 76.9 | 27.838 |

Key findings

Our study’s initial results are very promising, though future iterations of our work must have a larger scope and scale to yield truly convincing results.

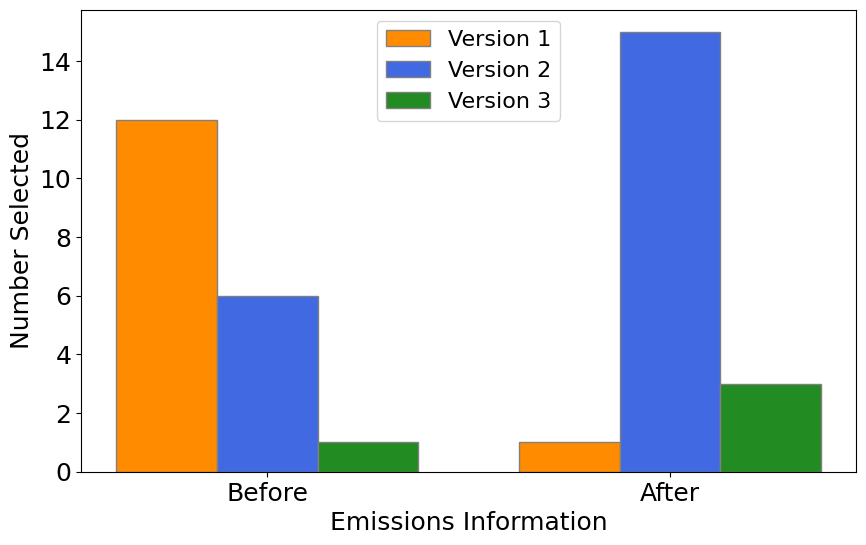

Before knowing emissions information, version 1 (the original website) was the most preferred amongst participants (63.2%), followed by version 2 (31.6%) and version 3 (5.3%). After participants were given emissions information, there was a noticeable change in the desirability of version 2 (78.9%) over version 1 (5.3%). In fact, version 3 (a stripped down website) was considered more desirable than version 1, with 15.8% of participants preferring it over the other versions. This demonstrates that participants displayed a clear desire to incorporate environmental concerns in their web browsing decisions.

The results in part 2 of our study reinforce the observation that users consider the environment to be an important part of their web-browsing experience. When given the opportunity to build a custom green website, participants tended to aim for a significant decrease in emissions, even at the cost of usability. For all 19 participants, the median reduction in emissions after customizing the page was 67%. The figures below show the distribution of changes individuals made. Clearly, there is a wide variety of aesthetic changes different users are open to. But, users seem to be unified by the desire for an environmentally friendly website.

Toward personalized sustainable experiences

In seeing individuals’ willingness to include carbon emissions in their UX while noting the lack of agreement on what specifically should be changed, we found a need for a customizable, individualized green-website service.

By asking visitors about their aesthetic preferences and carbon goals, websites could dynamically tune media resolution, feature sets, and styles to match each user’s individual needs. We are excited to see how future work in this area will be individualized and improved upon.

Grace Everts is a rising senior at Harvey Mudd College studying computer science. She is interested in the intersection between biology, climate, and computation.