The following article is the second part of the two-part series “The Story is a Forest.” Part one appeared in Branch Magazine Issue #1.

Narratives with Mass Resonance

In part one, we explored bottom-up, individualized climate communications, and learned this requires quite a bit of resources, like research, the construction of multiple narratives, and people on the ground willing to engage their peers. For this reason, possible top-down approaches, with the potential of ‘more for less,’ become incredibly tantalising. So are there any? As we gather more data on what connects to different identities, values and worldviews, some common themes emerge.

I call these ‘narratives with mass resonance.’ They are:

- Intergenerational responsibility

- Public health

- Prosperity

Intergenerational responsibility

Climate legal action is generally recognized to have started in the United States in the late 1980’s and early 90’s. To date, almost 1,000 climate change-related cases have been filed around the world, covering 25 countries. These cases are especially salient when they involve youth and children, as they represent the class most affected by government action or inaction.

In August 2018, at age 15, Greta Thunberg started spending her school days outside the Swedish parliament to call for stronger action on climate change by holding up a sign reading “School strike for the climate.” By 2019, there were multiple, coordinated city protests happening around the globe involving millions of people, many of whom were students. Her impact on the world stage has been described as the “Greta effect.”

Greta’s main talking point is that climate change will have a disproportionate effect on young people and that their futures are being stolen. This involves the concept of ‘Earth overshoot,’ that is, adults are consuming so excessively they’re using up the Earth’s resources, like freshwater, forests, fish stocks, etc. beyond their ability to regenerate and provide for future generations.

It’s difficult to quantify the effectiveness of the “Greta effect.” Motivating millions upon millions of people to engage in political activism for the environment does spread awareness of climate science, generate a critical mass of public engagement for politicians to see and has undeniably helped normalise climate change as a topic in the public discourse. In June 2019, a YouGov poll in Britain found that public concern about the environment had reached record levels in the UK since Thunberg (and Extinction Rebellion) had ‘pierced the bubble of denial.’

In February 2019, Thunberg shared a stage with the then President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, where he claimed: “In the next financial period from 2021 to ’27, every fourth euro spent within the EU budget will go towards action to mitigate climate change.” Climate change also played a significant role in the European Parliament elections in May 2019 as Green parties recorded their best ever result, increasing their MEP seat numbers from 52 to 72. Many of the gains came from northern European countries where young people had protested during Fridays for Future.

In July 2019, inspired by Thunberg, wealthy philanthropists and investors from the US donated about $600,000 to support Extinction Rebellion and school strike groups to establish the Climate Emergency Fund. Trevor Neilson, one of the philanthropists, said the three founders would be contacting friends among the global mega-rich to donate “a hundred times” more in the weeks and months ahead. Recently, and perhaps, relatedly, Jeff Bezos pledged to create a 10 billion-dollar Earth Fund. However, activists are justifiably skeptical about the mega-rich’s commitment to effectively dismantling the high-carbon economic system they built their wealth upon.

Thunberg can also be credited with accelerating the anti-flying movement by promoting train travel instead. The buzzword associated with this movement is “flight shame.” It’s a phenomenon in which people feel social pressure not to fly because of associated emissions and climate change. For example: Traveling from London to Amsterdam by train instead of plane can cut CO2 emissions by 90%. Sweden reported a 4% drop in domestic air travel for 2019 and an increase in rail. And the number of people flying between German cities fell 12% in November from a year earlier. Meanwhile, Deutsche Bahn has reported record passenger numbers and claims to be the largest user of renewable power in Germany today.

And yet, we’re beginning to see how highly publicized narratives like intergenerational responsibility are less resilient than peer-to-peer communications and are uniquely vulnerable to being co-opted. Recently, a 19-year-old German vlogger dubbed, “the anti-Greta,” Naomi Seibt, was promoted heavily by leading figures on the far right. Her mother, a lawyer, has represented politicians from the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party in court.

Seibt’s been quoted as saying, “Climate change alarmism at its very core is a despicably anti-human ideology.” She’s been employed by the Heartland Institute, a think-tank closely allied with the White House, to make climate denial videos.

Economic, political and social realities help determine which of these influencers will be favoured. People who are insecure, lacking access to education and medicare for example, and who live in societies with greater wealth disparity, like in the US, may be more likely to support strongman figures playing to their defence mechanisms. Whereas those who are secure may be more inclined to support figures advocating for courage, collectivism and action.

Public Health

Climate change is a public health crisis:

- The frequency, intensity, and duration of heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, floods and storms are increasing

- As average temperatures rise, so will heat-related disorders

- Air pollution and relatedly, respiratory illness, can worsen

- High CO2 concentrations are associated with decreased mental performance

- Climate change increases the transmission of certain diseases;

- Creates food insecurity

- Causes mass migration and, most likely, increased violence

- And threatens our mental health and well-being (e.g. eco-anxiety)

As leading health experts have affirmed, the climate crisis is a threat multiplier, particularly for communities suffering from environmental injustice. And, climate change isn’t a future risk, the impacts are occurring now. However, as we explored in part one, fear narratives, like focusing only on climate change’s many adverse health effects such as those listed above, can trigger defence mechanisms. This is why the topic of public health must be handled carefully, and even, cleverly.

We may look to a few historical examples of moments when a public health crisis fuelled by environmental abuse mobilised political action. In 1952, a thick layer of smog settled over London, England. This severe air pollution event was caused by the city’s excessive use of coal and lasted five days. It’s estimated up to 12,000 people died and 100,000 more were made ill.

Environmental legislation since the Great Smog of London, such as the City of London Act 1954 and the Clean Air Acts of 1956 and ’68, introduced measures to address air pollution, like the mandated movement toward smokeless fuels. Financial incentives were offered to households to replace open coal fires with alternatives, such as gas fires. Some talking points used to gather support for such measures were the social and economic costs of air pollution, and that clean air was as important as clean water. This is clever messaging because it normalises clean air by comparing it to clean water, which was already viewed favourably and had been successfully fought for in the previous century.

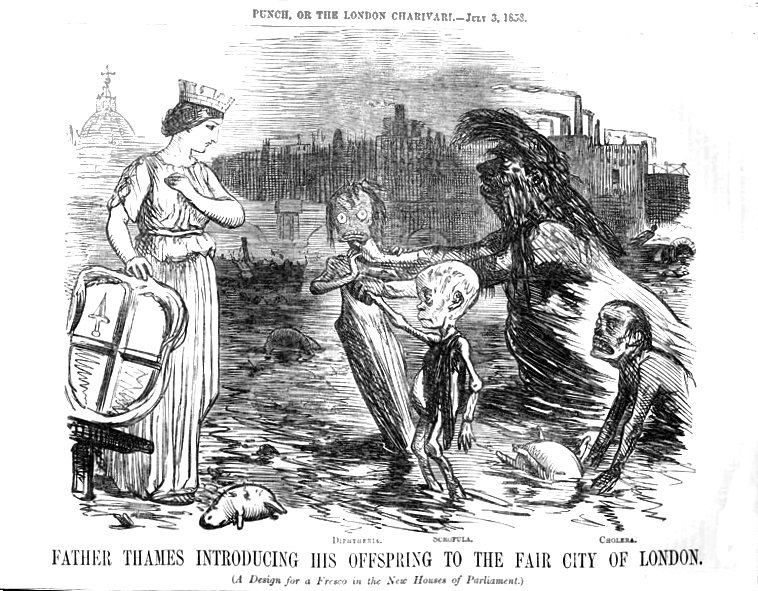

Why had it been fought for? Well, before the Great Smog of 1952, there was the Great Stink of 1858. The Great Stink happened when hot weather brought out the smell of human and industrial waste present on the banks of the River Temes. This waste was also linked to the transmission of cholera.

It’s here we see a great example of environmental action through satire, with many cartoons of the day highlighting the unacceptable state of things and mocking government inaction.

Following the Great Stink of London, government authorities accepted a proposal for an integrated and fully functioning sewer system from the civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette. This marked the beginning of London’s sewage reform.

During the 1970’s and 80’s the ozone hole was identified by scientists, which is linked to an increase in skin cancer. The hole was caused by the use of manufactured chemicals. An international treaty to phase out a number of these chemicals, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, was agreed to on the 26th of August 1987, and entered into force exactly two years later.

With the parties to the Protocol having phased out 98% of their ozone-depleting substances, they saved an estimated two million people from skin cancer every year. It’s speculated the Protocol was so successful because much of the negotiation was held in small, informal groups. This enabled a genuine exchange of views and created trust. The people negotiating the treaty also included scientists, which lent credibility. We must also note that the ozone-damaging chemical industry didn’t have the lobbying power fossil fuel companies have today.

While critics could claim most governments merely philosophize about what an emergency response to climate change could look like after declaring a climate emergency, the coronavirus pandemic propelled countries globally into radical economic, political and social measures, including ‘shutting down the economy,’ that is, closing shops, cafes, restaurants, etc. as well as borders to mitigate the spread of the virus. These measures could certainly be described as anything but business-as-usual — and as reflecting an emergency taken seriously.

While these responses have been imperfect, and there is much to criticise, it’s worth wondering why the pandemic mobilised action in a way climate change hasn’t. As we explored earlier, some reasons are that climate change is relatively slower to show its impacts, and it’s larger in scope and therefore requires a multi-solutions approach representing a heavier cognitive load (i.e. it’s not ‘solved’ by a silver bullet technology like a vaccine). Plus, years of corporate lobbying has spread disinformation and slowed action. Moreover, the coronavirus feels personal. That’s because it’s spread person-to-person and invades the body. Could a greater narrative emphasis on the body — such as the presence of microplastics in our digestive tracts or pollution in our lungs — spur more climate action?

Images of nurses with mask-creased faces — red and bleeding skin — invaded our social networks accompanied by the hashtag #StayHome, invoking wartime propaganda asking people to ‘do their part’ and glorifying sacrifice. We will see the same messaging if the climate crisis worsens. While indeed everyone has a part to play in climate change mitigation and adaptation, it’s essential we counter messages that distract from government accountability and position avoidable suffering as acceptable. Key to this is creating alliances between essential workers — medical professionals, educators, grocery store clerks, etc. — and activists.

Over the years, the ecofascist idea that civilisation is fundamentally in conflict with the environment and Malthusianism, which advocates for population control as a means to avert resource insecurity (leveraged as a racist dog whistle, shifting blame to largely non-white countries experiencing higher birth rates while ignoring the climate impact of high-consuming, largely white countries), have seeped into the public imagination. In addition to this, ‘learned helplessness’—when a person comes to believe they cannot change a situation and therefore stops trying —could result when climate collapse is accepted as possible, if not probable. The coronavirus on the other hand, carries no such baggage.

However, in the instance of COVID-19, we again see how large narratives of courage, collectivism and action can be countered with defence mechanisms, individualism and inaction. Anti-vaxxer conspiracy theorists are criticizing the coronavirus vaccines, linking them to, of all of things, 5G communications networks.

In the US, the epicenter of the anti-vaccination movement is the Children’s Health Defense (CHD). CHD has spread the rumor that the COVID-19 lockdown was being used opportunistically for the installation of 5G masts. It also ran a piece suggesting the pandemic provides cover for a “global agenda” trying to make us all “subjects of a techno-communist global government,” ideas and verbiage redolent of those espoused by ecofascist Ted Kaczynski— also known as the Unibomber— in his manifesto “Industrial Society and its Future.”

Prosperity

Some prosperity narratives focus on how climate action can raise resource efficiency, and stimulate innovation and new investment in infrastructure to improve the economy. However, as we’ve explored, our current economic system, which aims for infinite growth, is a major driver of climate change. It’s therefore necessary we reconceptualise prosperity; prosperity not as an ever-increasing GDP, but as financial stability and meeting — not exceeding — one’s needs. Importantly, this will involve narratives that challenge consumerism and the myth of ‘green growth,’ and relatedly, the concept of decoupling.

Relative decoupling refers to a decline in the ecological intensity per unit of economic output. In this situation, resource impacts decline relative to the GDP, which could itself still be rising. In other words, total material throughput and emissions can continue to rise. Absolute decoupling refers to a situation in which resource impacts decline in absolute terms. Sufficient absolute decoupling remains unproven and, when we’re running out time, we can’t afford to make decisions based on wishful thinking when we know what works now.

Prosperity doesn’t only have material associations, it can also refer to experiences that help us thrive physically, intellectually, emotionally and spiritually. Walking through a forest, access to a community of people we care about, exercise and growing a garden are all experiences with low planetary impact.

“Growthism is anti-intellectual in the sense that it prevents us from thinking about what we actually want the economy — and our society — to achieve. GDP comes to stand in for thought itself.”

– Jason Hickel, Economic anthropologist

One environmental movement that focuses on re-imaging prosperity is Degrowth. Degrowth emphasizes the need to reduce production and consumption in the Global North and advocates for a socially just and regenerative society with well-being as indicator of prosperity instead of GDP. Well-being can include, for example, life expectancy and self-reported life satisfaction and happiness.

The movement relies heavily on economic data to support its claims. For example: Indicators of well-being are higher the more equitable a society is, in other words, people are happier in societies where wealth disparity is small. What we find is well-being isn’t exclusively coupled with GDP growth. Not to mention, climate change (as it’s linked to GDP growth) would certainly negatively impact people’s well-being.

“The real power of GDP growth, as a metric and narrative, is that it’s just enough to convince people that this system is working who would otherwise be quite aware that it’s not.”

– Hickel

28% of all new income from global GDP growth over the past 40 years has gone to the richest 1% (all millionaires). In other words, nearly one third of our labour, resource extraction and CO2 emissions have been done to make rich people richer.

Hickel also makes the point that, in psychology, the capacity for self-restraint in the face of excess is considered to be a mark of maturity, empathy and wisdom. And yet, applying this principle to consumption is considered unthinkable. These degrowth talking points both challenge the economic growth paradigm and offer a new vision of prosperity that centers humans and the environment.

Mutually-Reinforcing Talking Points

Intergenerational responsibility, public health and prosperity narratives can be combined to create a holistic approach to climate storytelling. Since each of these topics benefit from climate change mitigation and adaptation, communications professionals can lead with climate or with a co-benefit. Here are some examples:

- Leading with climate: “We have a responsibility to solve climate change to make sure everyone, especially our children, can lead healthy and prosperous lives”

- Leading with a co-benefit: “We can reduce death, illness — and financial costs — from climate change if we prioritise our children, public health and prosperity”

Ideally, over time, climate action and its co-benefits merge so thoroughly they become one and the same.

Basic Plots

Christopher Booker argues there are only a few basic storylines: Overcoming the monster, rags to riches, the quest, voyage and return, and comedy, tragedy and rebirth. At the core of these examples are stories of various kinds of transformation through confrontation: Social, economic, spatial and personal.

Could fitting the climate issue into these familiar plots help connect it to people? Could the ‘monster’ we need to overcome be climate change? Or perhaps, corrupt elites, like fossil fuel CEOs and colluding governments, who have profited at the planet’s expense — at our expense? How might we tell a rags to riches story that rejects our current conception of prosperity? How about a homecoming story: We build a closer relationship to the environment — in this way, returning to ourselves as part of it?

There are few aesthetic and literary movements associated with positive climate action, like afrofuturism. Another that’s gaining popularity is solarpunk. Solarpunk creators imagine what a sustainable world could look like, and how we can get there. Solarpunk typically features Art Nouveau motifs, heavily greened cityscapes, diversity and community, and of course, solar and wind power. But, solarpunk is still quite niche. There’s much work that needs to be done here.

We’ve just thoroughly explored climate change communications: Its history, the status quo and potential experiments in storytelling. We’ve learned that our ever-evolving understanding of climate science should be at the core of all our communications, and that a good faith, one-on-one conversation is the most resilient but small-scale form of engagement on climate change. And, narratives relating to intergenerational responsibility, public health and a re-imagined concept of prosperity are particularly effective at inspiring large audiences towards action — yet are less resilient, and are especially vulnerable to being co-opted.

These micro and macro climate communications work together, offering an entry point to lasting change: A deeper confrontation with — and transformation of — our relationship to the environment, each other and ourselves. Informed by climate science and ecology, what’s common to all these narratives is a different way of being in the world: A rejection of the idea that our relationship to the environment and to each other is fundamentally extractive and adversarial. The truth is we have the capacity for both selfishness and generosity, and we can make choices about how to be and what will enable us to collectively survive.

Indeed, climate change may be the worst story ever but it’s also not a terribly new one. The first human adaptation known to us is hunting and gathering. As early tribes realised the importance of food security and strength in numbers for their survival, they developed stories to reinforce supporting behaviours. These stories warn of anti-social behaviours, like deception, stinginess, and theft, which could put groups at risk of food stress. This is famously embodied in mythological trickster figures.

As we take a closer look at the environment, its interdependencies, tensions, temporalities, processes, etc. may become more familiar to us. But there’s much we cannot perceive or measure. Once we let go of the idea the environment is totally calculable and therefore controllable , we can also abandon the harmful notion that everything in nature can be assigned monetary value. We can begin to understand the environment as a humble approximation and conservation as an act that is good-in-itself.

Only then can we truly integrate regenerative behaviours into our lives, becoming better stewards, collaborators and observers of the many people and organisms we encounter. We will have ‘written a story’ worth living for.

About the Author

Christine Larivière is a digital communications strategist, manager, and analyst with a data-driven approach who’s working on climate change mitigation and adaptation.