A story exists in the world about a giant tortoise that was collected in South Africa by crew members on the ship of the explorer Captain James Cook and gifted to the King of Tonga. They were named Tu’i Malila and when they died they were sent to the Auckland Museum to be preserved. The Reuters report on the death of Tu’i Malila was included as an epigraph for Phillip K. Dick’s influential novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep.

It reads:

A turtle which explorer Captain Cook gave to the King of Tonga in 1777 died yesterday. It was nearly 200 years old. The animal, called Tu’imalila, died at the Royal Palace Ground in the Tongan capital of Nuku, Alofa. The people of Tonga regarded the animal as a chief and special keepers were appointed to look after it. It was blinded in a bush fire a few years ago. Tonga radio said Tu’imalila’s carcass would be sent to the Auckland Museum in New Zealand.

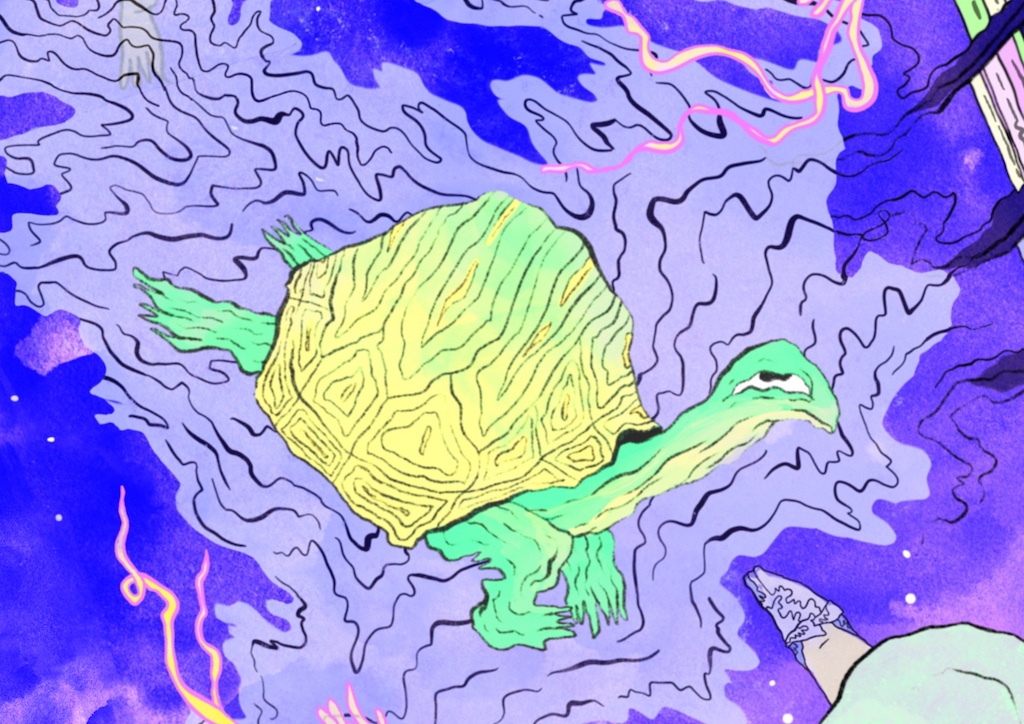

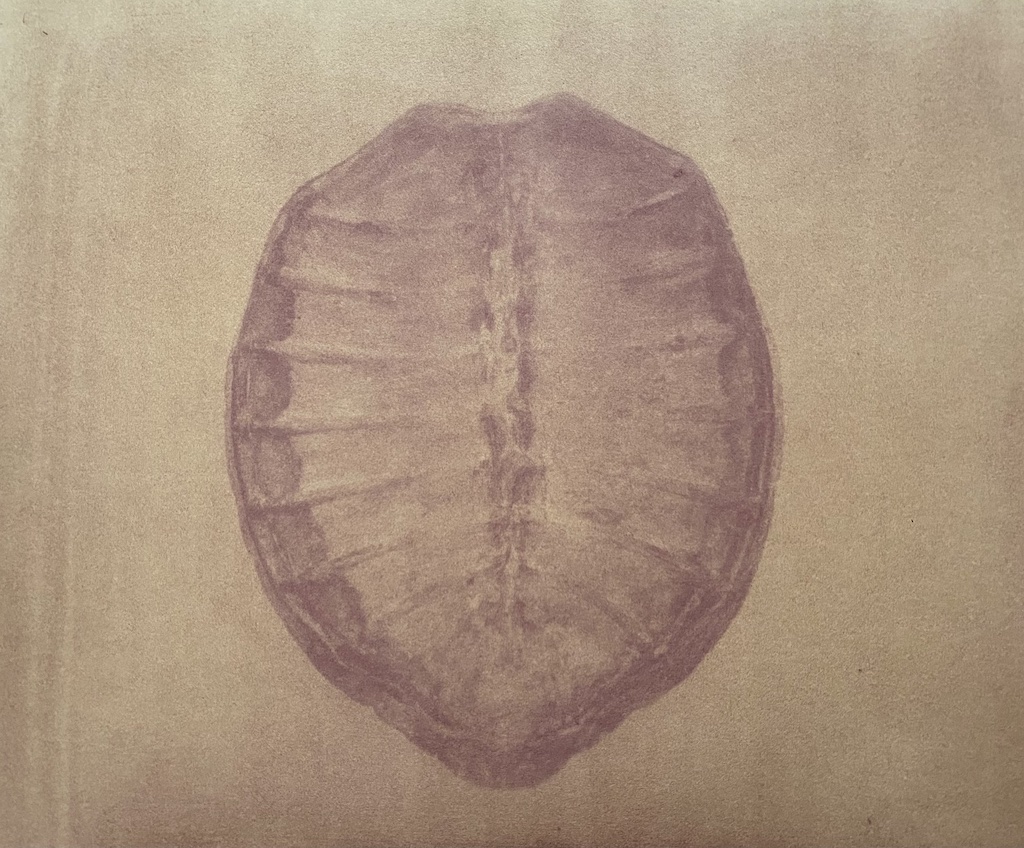

We view the story of Tu’i Malila as an inspiration for Dick’s speculative vision of a world mourning mass extinction, hunting rogue androids, and pondering what it means to be a human being. However, curators at the Auckland Museum — professionals impossibly tasked with preserving human and non-human memory in an always entropic world — would later complicate the narrative with an alternative reading of the story: Tu’i Malila was classified as a Madagascan Radiated Tortoise, with characteristic brownish-yellow lines radiating from the center of each of the shields of their carapace. They presented as biologically female and over their lifetime their shell protected them: the curators noted dents from a horse kick, markings from the wheel of a cart and a split from a fire which also blinded Tu’i Malila. Rather than a gift to the King by Cook, it is more likely that the tortoise was captured and carried on ship as fresh meat, sustenance powering the violence of colonial expansion, and gifted by crew to Tongans.1 Tu’i Malila still stands as a symbol of colonial interaction that was also revered for its unusual life span, then the longest living tortoise recorded by human beings.

This story, its literary influence, and its curatorial dismantlings, intersect with our ongoing project Fugitives, in which we use research-creation practice to highlight the generative force of entropy in museums and archives in which things are always breaking down and becoming something new.2 Dick, too, was concerned with an analogous force he called kipple, “…a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.”3 We are attuned to the fleeting nature of all things in tension with the human-institutional impulse to document and preserve — that is, to live and to be remembered. This orientation brings a melancholy tenderness to our practice, in which we honor the nowness of our collaborations, our personal and family experiences, our more-than-human relations, and their deep entanglements in our creative work and writing across art and anthropology. For the literary critic N. Katherine Hayles, Dick’s androids make visible “the unstable boundaries between self and world.”4 Boundaries are made unstable by the force of entropy and our fugitive worlding relationalities.

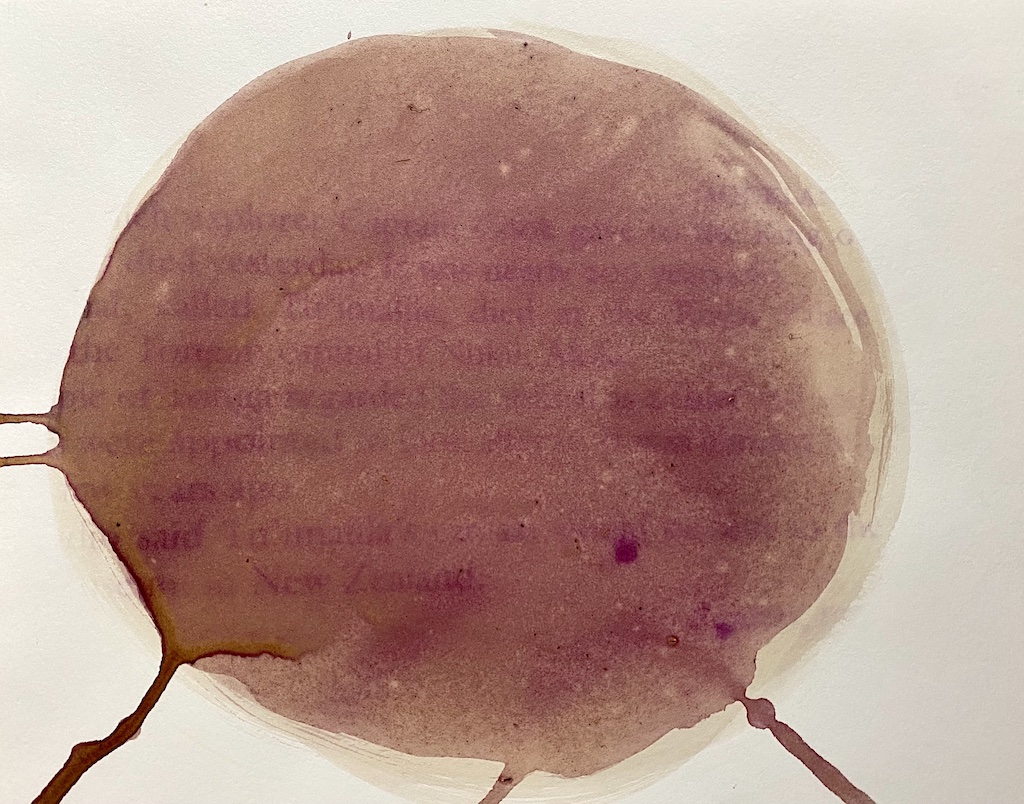

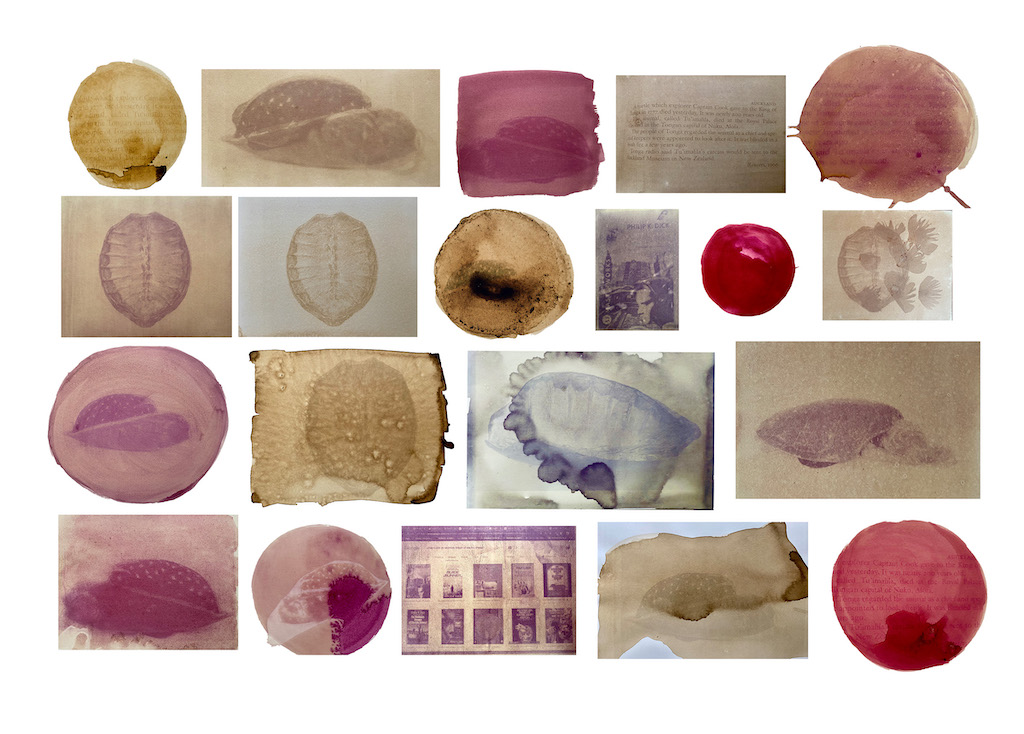

Compelled to respond to these interwoven stories, we created a series of anthotype prints, titled “Fugitive Memory: for Tu’i Malila.” An emulsion made with stinging nettle and rose petals (plants connected to our own childhood memories in British Columbia and Alberta) and processed outside in the summer sun reorients the images in greenish-brown and magenta hues which we then photographed digitally to accompany this essay. The tortoise shell in the images is a family heirloom that Trudi’s grandfather, a Scottish settler to Nova Scotia and ship’s engineer, collected in the course of his travels. In the now, this tortoise being raises questions about the reshaping violence of colonial encounters and a call to responsibility. Trudi remembers the shell as a child, hiding underneath it, rocking in it, curling into the shape of the absent body. Drawing the thread of her memory through our interest in Dick’s epigraph, we borrowed the shell to photograph. Kate’s daughter, at that time seven years old, was invited to recreate Trudi’s childhood memory. Her toes peek out from under the shell, her long hair and unicorn-print dress spilling out, her small body protected by the carapace.

Anthotypes are a plant-based photography made with plant extractions: leaves, stems, berries and flowering heads. The photographic process is known as fugitive, as the images fade faster than other processes, becoming anarchival. Anthotypes are an appealing medium in our practice because they connect us to an everywhere sense of impermanence, to growing and gathering and processing with plants, and to a longer history of photography and human relationships with images and image-making. They are a slow and unpredictable practice, allowing for an intimate sensory exploration of timescales, bodies and memories.

We are fascinated by the longevity of a tortoise who exceeds all human lifespans. What did they see in their long life, what memories did they keep beyond the marks of the world on their shell-archive that curators could observe? In Dick’s novel, most animals have long since become extinct, androids fight for longevity, and the bounty hunter Deckard’s belief in his humanity is measured through memories represented by photographs. The story of Tu’i Malila that influenced Dick’s novel is itself revealed as an unreliable narrative, transformed by science, but perpetuated through his art. Trudi’s memory of a tortoise shell, the curious intimacy of being with it, lives on in the more recent experience of Kate’s daughter as she folded herself into the shape of that same creature; memorialized, for a time, in these fugitive images for the rest of us.

What is it to be alive? For us, today: to remember a giant tortoise, to make art with a dear friend, to weep for the burning planet, to hold your child in your arms who will never, ever be this small again.

Further Reading

Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. New York: Doubleday, 1968.

Hayles, N. K. How We Became Posthuman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Hennessy, Kate, and Trudi Lynn Smith. “Fugitives: Anarchival Materiality in Archives.” PUBLIC 57. Archive/Counter-Archives (2018): 128–44.

Robb, J, and E.G. Turbott. Tu’i Malila, “Cook’s Tortoise.” Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum, 8 (December 17th, 1971): 229–33, 1971.

Slevin, Joseph R. “An Account of the Reptiles Inhabiting the Galápagos Islands.” New York Zoological Society / Bulletin – New York Zoological Society (January/February, 1935), 2–24, 1935.

Smith, Trudi Lynn, and Kate Hennessy. “Anarchival Materiality in Film Archives: Toward an Anthropology of the Multimodal.” Visual Anthropology Review 36, no. 1 (2020): 113–36.

Kate Hennessy is Associate Professor specializing in Media at Simon Fraser University’s School of Interactive Arts and Technology (Canada). As director of the Making Culture Lab, her work uses collaborative, feminist, and decolonial methodologies to explore the impacts of new memory infrastructures and cultural practices of media, museums, and archives.

Trudi Lynn Smith has a PhD in studio art and anthropology and specializes in research-creation. She is Adjunct Associate Professor in the school of Environmental Studies at University of Victoria, Canada, and is a clinical counselor. Her work embraces expressions of belonging, impermanence and change in communities of art, archives, ecology and collections.

- Robb, J, and E.G. Turbott. Tu’i Malila, “Cook’s Tortoise.” Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum, 8 (December 17th, 1971): 229–33, 1971.; Slevin, Joseph R. “An Account of the Reptiles Inhabiting the Galápagos Islands.” New York Zoological Society / Bulletin – New York Zoological Society (January/February, 1935), 2–24, 1935. ↩︎

- Hennessy, Kate, and Trudi Lynn Smith. “Fugitives: Anarchival Materiality in Archives.” PUBLIC 57. Archive/Counter-Archives (2018): 128–44.; Smith, Trudi Lynn, and Kate Hennessy. “Anarchival Materiality in Film Archives: Toward an Anthropology of the Multimodal.” Visual Anthropology Review 36, no. 1 (March 2020): 113–36. ↩︎

- Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. New York: Doubleday, 1968, 66. ↩︎

- Hayles, N. K. How We Became Posthuman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999, 160. ↩︎