As demand for minerals, water, and land for ‘green’ transitions and technologies increases, we feel it’s necessary to name the inherently extractive systems at work, and highlight the violence in affected territories. At our workshop in Heredia, Costa Rica1, with participants from around the world, we discussed the socio-environmental impacts of digital technologies and their macro-narratives of development in affected territories, in both the Global North and South. The insights gathered here reflect the work of many people sitting and thinking together in a garden.

We understand extractivism as a set of state and private (sometimes transnational) measures to invest public and private resources in the extraction of raw materials which are considered strategic for national economies. Extractivism often increases foreign debt and establishes financial agreements with countries of the Global North and China, which indebt the countries supplying the raw materials. In the context of Latin America, it has been redefined as neoextractivism, shaped by a commodities consensus2 based on the dynamics of large-scale exportation of raw materials.

The term ‘raw materials’ itself should be questioned as it contributes to the neo-extractivism narrative by preparing the ground for the appropriation and transformation of relations, territories and memories into ‘natural resources’ or ‘materials’.

Building on this definition, we want to define additional types of extractivism, which account for the power structures and epistemic violence that reproduce inequalities within different spaces, so that we can move towards decolonial forms of coalition. This is because extractivism is also about historical violence on bodies and territories which extends the understanding of socio-technical violence3. This concept is applied to a more complex web of dispossession that produces dominant world views, livelihoods, and models of existence and subjectivities. We connect this to the Body Territory defense, and disputes over technological and knowledge-producing infrastructures.

Together, in three languages (English, Portuguese, Spanish), we developed a mixed methodology that combines a general structure for extractivism with provocative questions and work tools that connect the body with the defense of territories, in order to bring real-life cases to the discussion. A few questions guided us:

What is the relationship between mega-investments in infrastructure for digital technologies, water use and other forms of territorial appropriation in the Global South?

What are the macro-narratives associated with digital technologies, and the neocolonial and cis-hetero-patriarchal relations that occur in zones of extractivism that are superimposed on territories and lands?

What are the multiple strategies of resistances from the local communities against these extractivism practices and mega-projects?

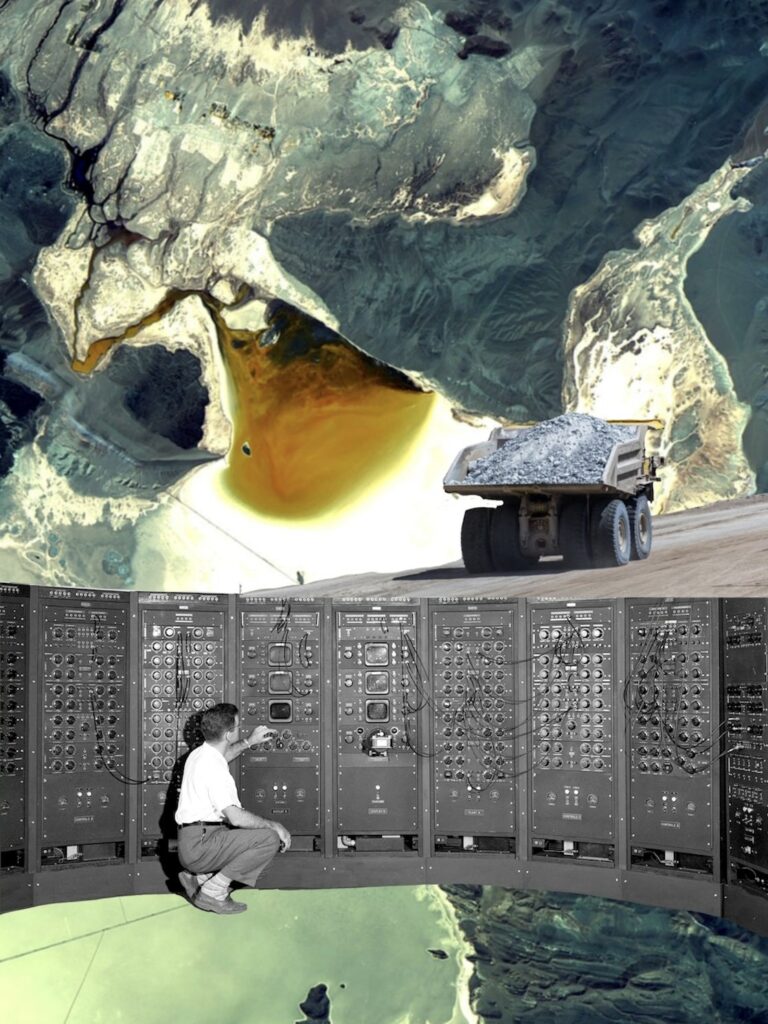

First and foremost, it’s worth noting the existence of different interpretations of the word ‘extractivism’. Some Amazonian communities which have a positive understanding of the term call themselves extractivist communities, or communities that live in extractive reserves. These communities practice a type of organic extractivism based on the sustainable management of the territories. A different type of extractivism, which we call ‘synthetic extractivism’, is focused on the macro-level expropriation of territories through mining, logistics infrastructures, and energy megaprojects (for instance, hydroelectric dams). It includes the extraction of raw materials from territories in the Global South, especially the Pan-Amazon region, which is currently at the center of the climate agenda. Mining is one of the most damaging extractive processes in the plundering of natural resources which constitutes Big Tech’s ‘production chain’. The case of lithium extraction is well-known, but recognizing the interdependence of extractive projects is key to advancing the debate.

In the course of our discussion we identified the following insights:

a) Migration: goods can travel but not people. Refugees cannot cross borders but resources, understood as commodities, can.

b) Technologies impact the continuity of life in multiple ways.

c) Natural resources (e.g. water and energy) are needed by large companies.

d) Legislation is problematic when it is not decided through horizontal decision-making processes.

e) Exploitation of labor and bodies occurs through colonial, cis-hetero-patriarchal hierarchies.

f) Informational black boxes: we do not know how big companies handle information about local communities and territories.

g) Multidimensional transparency which goes beyond narrow forms of transparency controlled and implemented by the corporations themselves.

h) Social-environmental activists who defend territories face different layers of violence and risk. This also goes for journalists, local communication networks and engaged scholars, who face pressure by governments and paramilitaries.

i) Data extractivism exists within colonial systems of oppression. Debate on the subject needs to be expanded within social movements, traditional communities and the collective coalitions that have built paths of territorial defense and land rights for decades.

In view of the somewhat bleak scenarios pertaining to misinformation in different regions, we also identified the need to build more horizontal alliances, or bridges, not only to think of possible future options, but also to begin taking concrete action. We imagined the following bridges:

Bridge 1: Open safe spaces for meeting and exchange between organizations. People welcome in these spaces include, among others, feminists and sex-dissident people, youth, members of the agro-ecological movement, the climate movement, and movements for the democratization of communication in different dimensions. We call these spaces local/territorial caravans since they operate in territories affected by extractivism, where being on the move is an important political strategy in the struggle for life. To amplify understanding of communication processes and documentation, and go beyond individual and isolated perspectives, we must understand territories geopolitically located in the Global South as well as in the Global North, for example, the struggle against coal mining in Germany.

Bridge 2: Organize tactical opportunities, based on the concerns of different communities. Rethink the language used by funders, because funding rules don’t change easily. This includes broadening the scope of digital rights.

Bridge 3: Establish and nurture transnational connections to share new ideas that counter dominant narratives. Talk across geographies, while recognizing efforts from the Global South to build direct criticism of the Global North’s dynamics. Look beyond the cases and experiences that fit into dominant narratives.

Bridge 4: Funding agencies and NGOs in the Global North should reflect on how they manage their collaborative processes so as to bring digital rights closer to the terms of the debate used by the Indigenous populations, as well as other communities affected in different dimensions.

Bridge 5: Fund decentralized infrastructures that allow the participation of local organizations in the decisions about cultural and economic alternatives for their own territories and lands.

Bridge 6: Building coalitions and alliances on the basis of recognition and respect to develop paths that support historical movements which build in collective ways and use horizontal forms of cooperation. Do this in favor of combining people from different territories in operationally-centralized forms of project. Develop cross-border and shared collaborations in place of isolated formats, for example, actions that self-organize and build together.

In conclusion, the perspectives developed here should be present within the global agenda so that alternatives can be developed and discussed. Debate on structural transformation should also be raised, so that sociobiological information pertaining to ancestral territories can remain under the guardianship of the peoples who have managed these lands for thousands of years.

Kuirme Collective is composed by Rub(én) Solís Mecalco, Aymara Llanque, and Camila Nobrega, three of us with an academic and activist mixed background between Latin-America and Europe, focusing on multiple layers of extractivisms from feminist and territorial perspectives. Bringing our trajectories together, we want to build critical lenses on green capitalism, fostering imaginaries and actions from rural and urban Abya Yala (Latin America), contributing to dialogues between the territories we inhabit, both in Latin America and Europe. In our last project, the Kuirme Collective was interested in the co-creation of common responses on the following key issues: a) extractivisms in digital and non-digital contexts b) exploitation of the commons for digital development and its consequences on climate; c) prospects for forest conservation with carbon settings versus prospects for reparations and historical repayment of climate debt.

Footnotes

- Acknowledgements to Marie-Therese Png who participated as a facilitator during the workshop in Heredia, Costa Rica. ↩︎

- Svampa, Maristella. 2019. Neo-extractivism in Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- Ricaurte, P. (2022). Descolonizar y despatriarcalizar las tecnologías. La razón extractiva. México. Centro de Cultura Digital, p.14. ↩︎