The Demonstrator is a publication emerging from the ongoing Designing Regenerative Technologies project run by Dutch public research institute Waag Futurelab. Part of the project’s agenda is dedicated to exploring and amplifying regenerative practices among artists and creative technologists. The Demonstrator shows ways in which computational creativity can meet ecological consciousness, highlighting alternative pathways for making and thinking with technology.

The publication features artists, designers, and researchers who challenge dominant narratives of computational progress. Rather than prioritizing efficiency or scale, these contributors use digital tools to cultivate care, slowness, and life more attuned to our actual needs.

A central thread in The Demonstrator is the exploration and application of permacomputing – a radically (slightly) more sustainable approach to computation. Drawing inspiration from permaculture, permacomputing invites us to think about computation as something that can be practiced through conserving energy, embracing decay and reuse, valuing simplicity, and fostering long-term ecological strategies.

We assembled a diverse set of artists’ profiles whose work illustrates one or more principles of permacomputing and regeneration. They also share their hopes, fears, and experience of venturing into this field. More than a catalogue, The Demonstrator is an invitation to imagine innovative and most of all sustainable modes of techno-cultural production. It challenges extractive paradigms and instead offers practices rooted in mutualism, resilience, and creative resistance.

Why focus on creatives?

There is no clear, singular path that would take us to a future where our design and use of technology do not cause harm. Until now much research and scientific work is devoted to achieving sustainability. But we must ask: What exactly are we trying to sustain? Many sustainability efforts fail to reckon with the resources already depleted and the damage already done.

To rethink harmful practices and redesign patterns that got us here, we need new imaginaries, provocative ideas, and practices that encourage us to experiment. That’s why this publication turns to pioneering designers, makers, writers, hackers, and artists who approach technology on their own terms, with a deep awareness of its consequences on the environment.

What does it mean to be an artist engaging with topics of permacomputing and regenerativity?

In our conversations with the artists, some key themes have emerged. Deciding to take up principles of sustainability, regeneration, or permacomputing as a focus of their work often means that creatives find themselves invigorated by the new uncharted territories, but simultaneously face a lot of uncertainties and precarity that obstruct their practice.

So, what does it mean to step into this field?

To roleplay as a scientist

Since we currently cannot achieve full regenerativity in our relationship to technology, this means we have to become comfortable with experimentation. There has been a lot of knowledge about sustainable practices developed in the last few years, but this knowledge is often gatekept at universities or in the hands of specialists – this does not have to be the case!

The artists of The Demonstrator all have adopted an approach in which they dive into unfamiliar skills and genres with the simple belief that their curiosity will carry them forward in their experiments. This means starting small, taking time, and continuing to engage with a problem even if you haven’t mastered the required skills (just) yet.

To take time

The current digital landscape offers little opportunity to slow down and cultivate a computational culture that fosters deep engagement and ecological relationality. Artists in this series of interviews voiced the need for frameworks that would make it easier to allow for the flourishing of a culture where we are not merely passive adopters of technologies but thoughtful participants.

Slowing down means resisting the notion of going fast and breaking things, but rather looking back and reassessing what can be fixed. Artists within the permacomputing practice try to take more time and energy to immerse, test, and apply approaches that would make this possible.

To find community

To step into the relatively nascent field of permacomputing and regeneration can also mean that, as an artist, you might initially find yourself overwhelmed with unknowns and unsure where to start. Each artist we talked to in this interview series stressed how important it was for them to find and engage with communities where knowledge and skills already exist.

Some found out about working with soil directly from farmers, some of them picked up soldering skills from hacker meetups, and others found their support communities online. These various communities helped bridge gaps in knowledge and offered encouragement at moments when more conventional, fast-paced modes of working felt easier or more widely accepted.

It’s through these communities of practice (such as those forming around permacomputing) that artists find the support they need to keep exploring. They don’t just gain practical skills but they also find companionship in pushing back against extractive norms, and inspiration to imagine new ways of making, thinking, and being.

To be conflicted

Artists interviewed for this series have also been honest when describing their journey – due to institutional standards that impose extractivist practices on makers, it’s often impossible to freely embrace regenerativity and permacomputing principles. Open calls and design briefs tend to come with demands that directly contradict the ethos of regeneration, forcing artists to navigate constant trade-offs between staying true to their values and meeting professional expectations.

This could mean institutions requiring high-resolution files, unsustainable materials, or proprietary software that reinforces dependency on Big Tech, with disregard for what that means for the planet.

Artists are also concerned that, without proper financial backing, their experimental work will not be appreciated enough for them to continue to support their own practice.

The Demonstrator: Discover the artists of permacomputing

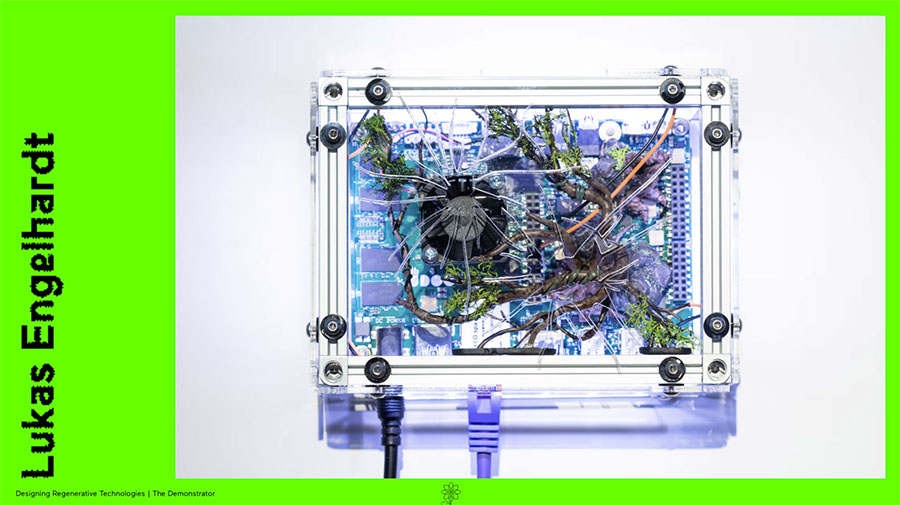

We now invite you to explore The Demonstrator, a collection of artworks and quotes by eight imaginative artists: Lukas Engelhardt, Sunjoo Lee (also see her article on The Gardening Electricity Handbook in this issue of Branch), Leanne Wijnsma, Rein van der Woerd, Anna Andrejew, Leo Scarin, Joost Rekveld, and Brendan Howell.

This mix of ideas, hacks, and hopeful experiments is here to spark your imagination on what ecologically-conscious approaches you could implement in your daily practice.

Designing-Regenerative-Technologies-Demonstrator-06-artist-only_compressedOla Bonati is a concept developer at Waag Futurelab. Her work explores alternatives to tech dystopia, seeking kinder, more sustainable practices for both people and the planet. Ola currently researches the relation between ecology and technology in Waag’s project Designing Regenerative Technologies. Since joining the permacomputing community in 2021, she has been actively engaged in workshops and talks, introducing creative professionals and the public to the concept of regenerativity. Ola frequently turns to writing (ranting) about technology but remains hopeful and playful by creating critical new media pieces and interactive interventions.

Judith Veenkamp leads the Urban Ecology Lab and the Life programme at Waag Futurelab. Judith has an interest in the role of technology in power dynamics. The research focuses on how technology can add value to society and be grounded in principles of regeneration, rather than extract from society and the planet.

About Waag Futurelab

Waag Futurelab reinforces critical reflection on technology, develops technological and social design skills, and encourages social innovation. Waag works in a trans-disciplinary team of designers, artists, and scientists, utilizing public research methods in the realms of technology and society. This is how Waag enables as many people as possible to design an open, fair, and inclusive future.

For more on permacomputing and Ola’s research, also see Alistair Alexander’s article in issue 8 of Branch: Care for life, care for the chips: the future is re-used, recycled and permacomputing.