In 2025, the urgency of the climate crisis and ecological devastation is well documented. While political and industrial leaders are eager to present new technologies as a way to engineer our way out of these crises, the resulting narrow sustainability efforts at best fall short of their promise and at worst intensify the extractive and exploitative models on which our economies are based. This begs the question: How can we move from this extractive model to one that is sustainable and equitable?

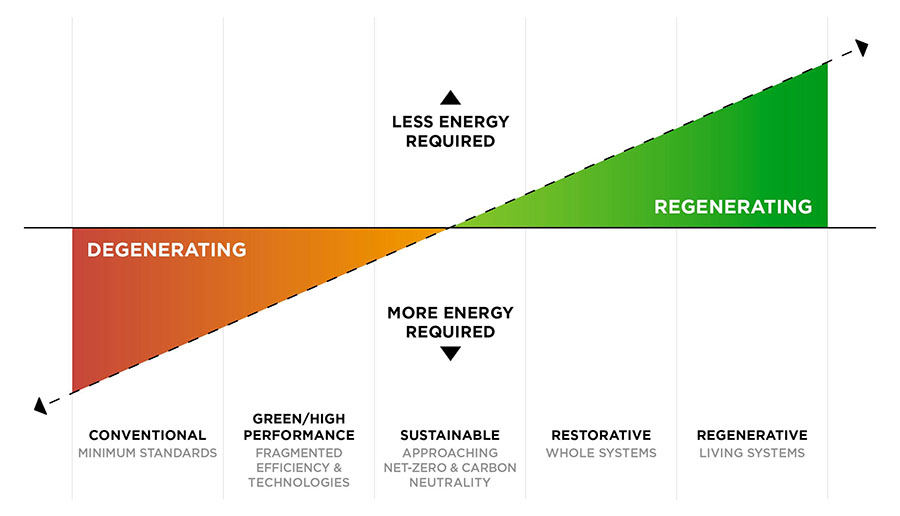

In his 2007 article “Shifting from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration”, architect Bill Reed offers a framework to move beyond maintaining the economic status quo by drawing attention to design practices aimed at restoring ecosystems and transforming underlying power structures to have more equitable outcomes. He argues that contemporary sustainability efforts are directed at “doing things better” rather than “doing better things”.

Doing better things, Reed argues, requires regenerative design: a place-based approach that engages with all stakeholders – human and more-than-human (i.e. nature) – to build equitable and healthy relationships. In a regenerative design, people and the planet are no longer seen as a resource for extraction but as an interconnected system in which every organism equally participates. These regenerative practices, or what others describe as being in good relation with the Land, are already applied on a small scale.

Restorative and regenerative infrastructures

In 2023, the critical infrastructure lab held a co-design workshop in Montenegro, and in the environment session, we asked participants to identify their favorite technology of nature. People looked around the building and brought back leaves to symbolize photosynthesis, branches and mosses to represent networks of trees, lichen, mosses, fungus, and worms to foreground composting processes.

This reminded me of the many ways technologies mimic natural processes – from renewable energy sources, like solar power, to the internet that mimics rhizomatic fungi and tree root networks. However, our technologies and infrastructures stop at the extractive and do not restore or regenerate what they have uprooted socially and environmentally.

Can we imagine alternative infrastructural practices that restore and regenerate? Not to offer one quick fix but to challenge our understanding of what infrastructures are and whose interest they serve to open up space to rethink the problem and the solutions at the right scale. Only by shifting our worldviews away from capital accumulation, optimization, and growth towards good relations with the Land can we create alternative futures that prioritize people and planet over profit and capital.

Breaking free from the mindset of the oppressed

To me, the words ‘extraction’ and ‘exploitation’ have become so normalized in relation to technology and infrastructures that these practices have lost their impact and true meaning. In a discussion on internet governance at the Green Screen coalition event, Indigenous activist Alana Manchineri asked if we could explain the word ‘extractivism’. After a few attempts, she looked at us and said “we just call this stealing”.

It was at that moment that I realized that in Western Europe and North America, we have lost the basic understanding of what it means to be in good relations with the Land. We have accepted that states and markets colonize our territories, homes, bodies, and minds for a sense of political and economic security. The first step in imagining alternative computational infrastructures, therefore, starts with breaking free from the mindset of the oppressed and seeing what is hidden, excluded, and missing from the debate.

Infrastructure that decomposes

Infrastructures are associated with the notion of permanence and durability, and the idea that they can only be designed and governed by experts. A highway collapse can have serious consequences to human life, and an electricity or internet outage is often quantified to its perceived economic damage.

However, at the 4S conference in Mexico in 2022, Miki Namba argued that infrastructures can also be soft and in good relation with the Land. In Laos, during monsoon season, bridges are regularly washed away and the choice of materials – bamboo vs concrete and steel – impacts the autonomy of local communities and the health of the Land. Where bridges are constructed from bamboo, the washed-away remains decompose in nature. New bamboo structures are easily rebuilt by local communities, allowing them – if needed – to change their location and reduce dependence on a central authority to come and fix giants of steel or concrete.

This simple bamboo structure challenges the notion of permanence in infrastructures, offering new avenues of agency in determining how our infrastructures are shaped and in turn shape society and providing avenues to imagine an end-of-life that does not disrupt but gives back to the Land.

Making choices

In an ongoing research project, we asked different stakeholders to design data centers in scarcity, i.e. what needs to be included in an infrastructure policy that focuses on limits, reduction, and redistribution instead of growth and capital.

We have found that designing in scarcity, rather than growth and abundance, allows people to explore demands and practices that would otherwise remain unimaginable in the contemporary infrastructure debate. It becomes about governance.

Where sustainability demands are directed at the state as a power holder, oppose the current focus on efficiency gains by the market, object to the neoliberal political calculus governing AI infrastructures, and demand public interest solutions. Specific demands center on drawing red lines on what type of data storage and computing is undesirable, prioritizing the allocation of existing and future infrastructural resources to public interest use, requiring large-scale computing and infrastructural projects to have an end-of-life plan, and developing an industrial policy that stimulates infrastructural practices that give back to the infrastructural ecosystem and technical community.

Redesign to be in good relation with the land

A restorative approach to computational infrastructures demands a redesign that concentrates on the keep-it-in-the-ground principle. To keep critical raw materials in the ground, we need to reduce the total volume of hardware used to power our infrastructures, extend the end-of-life of servers, sea cables, routers, and switches, and change server design.

For the latter, I will draw inspiration from Plantin and Marquet’s research, which found that recent design changes to servers and the architecture of data centers were fueled by the inability to significantly scale up computational power in a location due to the physical limits of cooling techniques.

Facebook, through the Open Compute Project, pushed for changes in data center hardware (components, cables, racks, etc.) that made servers wider and heavier, which required adjustments to the floor and floor plan of data centers.

If we can radically change the hardware and physical environments that run our infrastructures to allow for more computing in one location, we could also radically redesign our hardware to allow for reuse and 100% recycling. This shift away from profit and capital towards infrastructures that are in good relation with the Land will not emerge from the market unless ecological considerations are imposed on the technology industry, and state subsidies support research and development into reusable and recyclable hardware.

Organic computing

A regenerative approach to computational infrastructures is about closing the loop from extraction to regeneration, figuring out ways in which our ‘hard infrastructures’ give back to the Land.

In the co-design workshop in Montenegro mentioned above, Maxigas commented that hardware design is historically determined: The silicon chip, a critical part of almost every modern electronic device, became the default way to process, store, and receive information. States and companies have invested and continue to invest billions in this semiconductor technology, and silicon chips have become the center stage of the geopolitical struggle over power.

In this billion-dollar race to the bottom, silicon chips are highly polluting due to the chemicals, toxins, and carcinogenic substances needed for their production, which has foreclosed other ways to assemble computers and servers. If states, as seed investors of technology, would invest in alternative approaches to computing, and think of post-silicon computing or compostable technologies, we might be able to move away from extraction towards regeneration.

Post-silicon computing would require finding other, non-polluting materials to process, store, and receive information. Branch has previously featured the Data Garden art project, which proposes “a carbon-negative data infrastructure that promotes unification between people, living systems and technology” (Clarke et al., 2021) by encoding information into DNA. And this 9th edition of Branch features the Electric Garden by Sunjoo Lee, who works with regenerative energy sources in her search for technologies that support life rather than harm it.

A pathway forward

These are just a few examples of how our computing infrastructures can be in good relations with the Land. These approaches go beyond the status quo and open up avenues to imagine and speculate about what can be – an important first step to get us to non-extractive and equitable infrastructural practices.

There is no silver bullet; we need to decolonize our minds, design compostable hardware, give agency back to the people, and choose the wellbeing of people and health of our planet over the accumulation of capital and power in the hands of a few.

* A longer version of this article is expected to be part of an edited volume entitled “Planear la salida: horizontes ecosocialistas en el capitaloceno”, published by Verso Libros.

Fieke Jansen is a co-principal investigator of the critical infrastructure lab and a postdoc researcher at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests are to understand power and conflict around the environmental impact of expanding infrastructures. She is also the co-lead of the Green Screen Climate Justice and Digital Rights coalition.