(Source: Sunjoo Lee).

My concern about the climate crisis – and the hidden cost of our electronics – led me to rethink how I create art. I started teaching myself how to incorporate regenerative energy sources, like solar panels, into my artworks and searched for technologies that support life rather than harm it and that encourage processes which nurture both culture and ecology.

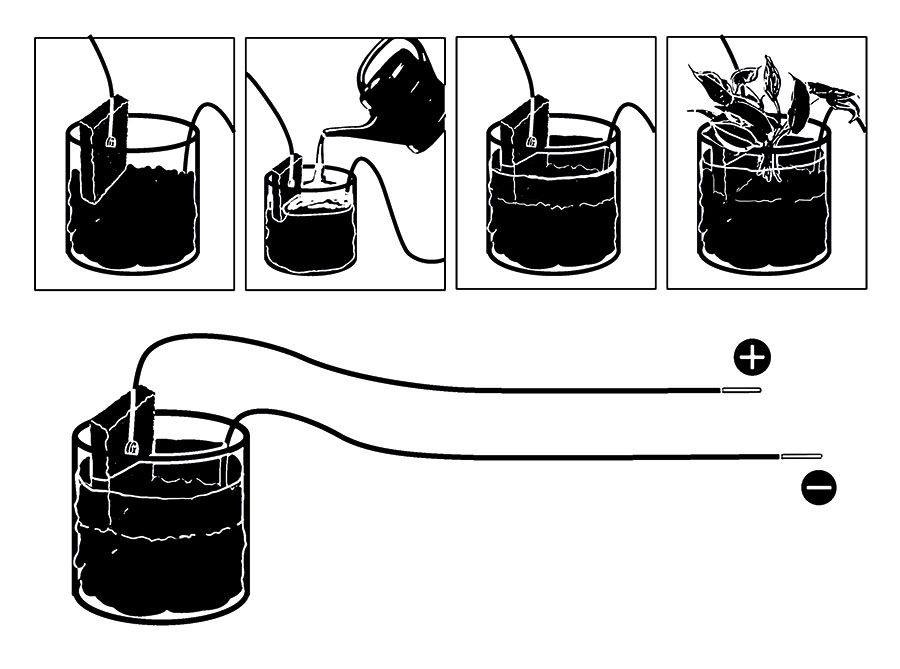

Soon, microbial fuel cells (MFCs) became the focus of my attention. They offer a novel possibility: an electricity generator that is, in itself, a biological ecosystem. MFCs harvest electricity from bacteria living in wet soil. By placing a conductive, non-corrosive sponge into a container of wetland mud, we cultivate electrogenic bacteria – such as Geobacter and Shewanella – that decompose organic matter in the soil as they metabolize. During this process they emit protons, gas, and electrons.

Introducing plants and insects into the mud cells creates a symbiotic relationship that helps sustain these bacteria. The plants give excess nutrients to the soil that bacteria can metabolize, opening up the possibility for gardens to generate electricity as a by-product of a thriving ecosystem. This marked the beginning of my research. The garden became a tool and a space for reflection in my ongoing effort to unlearn and relearn electricity. It eventually led me to broader questions about production, consumption, and sustainability.

An electric garden

In Utrecht’s Het Hof van Cartesius neighborhood, I built a 2 x 5 m garden that produces electricity, with the support from local residents and Creative Coding Utrecht. It’s known as the Electric Garden.

The garden consists of containers filled with wetland mud mixed with garden soil and fine sand from the area. Each cell contains two electrodes made from conductive sponge. After a few days, the electrogenic bacteria began to multiply and produce electricity. The process is similar to fermentation, which is about providing the right conditions for certain organisms to thrive. The bacteria adopt the sponge as their new home, and today the garden hosts a variety of perennial plant species, ranging from wetland to land plants, and insects such as worms, flies, bees, mosquitoes, ants, and spiders.

Microbial fuel cells have a lot of potential. Philosophically, they invite us to foster a different understanding of electricity, one that is more relational. Here, electricity is not just a tool or a product. It’s a part of the wild, undomesticated forces that exist in every corner of the material world. Bacterial metabolism and chemical reactions between liquids, minerals, and metals all involve the exchange of electrons. Taking care of the mud cells, whether in fermentation jars or as a garden, nurtures more than just electricity. It also cultivates vitality, curiosity, and a sense of connection to other species. It facilitates regenerative cycles of life, in sharp contrast to extractive systems that lack reciprocity.

Practical applications and future directions

Technically, the mud cells can be used for many applications, as long as we stay creative. Multiple cells can be wired in series or parallel to increase voltage or current. When connected to energy harvesting circuits, the system can power small electronic devices such as Arduinos, crystal radio transmitters, long-range transceivers, motors, clocks, LEDs, and buzzers.

It always takes a little while before the electronics can be powered up, as the energy needs time to accumulate. The electricity is small and uneven. It fluctuates depending on the time of day, the season, and the level of bacterial activity. This forces us to think carefully about how to use the energy and what we use it for. When energy is precious and limited, what choices do we make? How can we scale down our electronics instead of scaling up? What does degrowth look like?

I’ve seen the potential in this research as a relational and cultural practice: More and more people are building their own Electric Gardens. They started from the knowledge I shared through workshops and adapted my designs through their own experiments. The garden is spreading. I hope their journeys are just as inspiring as mine has been. I imagine cultures forming around the fermentation of electricity. What would they look like, and how would they treat and value energy?

Sharing the knowledge: the Gardening Electricity Handbook

To support this emerging movement, I’ve created the Gardening Electricity Handbook, a step-by-step manual for creating electricity-generating mud cells that involve electrogenic bacteria. Clear illustrations guide readers through the build, so that anyone can start their own Electric Garden. More manuals will follow, covering the circuits that can be used together with the mud cells.

Gardening-Electricity-Handbook-minI invite you to join this collaborative knowledge exchange and help grow the Electric Garden network.

Learn more about the Electric Garden on Sunjoo Lee’s personal website and the site of ongoing research project Tree-001. Electric Garden is generously supported by the Creative Industries Fund NL and Creative Coding Utrecht.

Sunjoo Lee is an interdisciplinary artist whose work bridges art, technology, and ecology. Based in both the Netherlands and South Korea, she’s fascinated by diverging the use of electronics and digital tools beyond human interest. Her practice often explores topics such as more-than-human philosophy, emergent systems, biomimicry, permacomputing, and future forms of symbiosis.

Sunjoo regularly collaborates with biologists, ecologists, and engineers to develop artistic research and create multimedia installations that celebrate the hybrid partnership of the biosphere and technosphere. She co-founded the research collective Getbol Lab and is currently an artist-in-residence at Creative Coding Utrecht.