It’s 2043, and across the planet, we are celebrating what sustainable and equitable digital infrastructure movements have accomplished. There have been revolts. There’s been cross-movement solidarity. Hope has been sustained over time. Ancestral knowledge has traveled across time, back and forth, infusing movements along its path. We’ve listened to the rhythms of nature. We are not yet enjoying the fulfillment of just futures, but we are much closer now – and we are celebrating.

To get here, we worked hard: listening to each other, building trust among ourselves. We had to collectively imagine the many branching paths we would be building towards. One of those collective imaginings happened 20 years ago, in one of the most biodiverse places on the planet, Costa Rica. The second Green Screen Coalition gathering brought together environmental justice and feminist activists, researchers, funders, technologists, communicators and community organizers for conversation and coalition-building at the intersection of digital rights and climate justice.

We, Janna and Paola, facilitated one of the gathering’s two day-long conversations. Our group reflected on what it would mean to re-design digital infrastructures from a sustainable and equitable perspective. We celebrated initiatives that were already preparing the ground for these desired futures. And we dreamt up collective visions of what our shared infrastructures could look like and the paths that could lead us there.

Let’s take a look back now.

It’s 2023

As we follow the branching paths of the garden, we notice a line of ants carrying bits and pieces of leaves. We get up close to admire their cooperative endeavors which sustain their community. We see how, along their path, they stop to help others who are carrying more than they can bear. Or how, when facing an obstacle, they create an alternate path and guide each other along. Like the ants, we now find ourselves at an impasse. In light of environmental breakdown and the climate emergency, we want to move from extractive, data hungry infrastructures to sustainable, regenerative, just ones. What can these new pathways look like, and how do we build them?

We came to this gathering inspired by radical optimism and diverse work within climate fiction that navigates towards hopeful futures while centering justice for those affected most by climate change and bearing the least responsibility for it. We came, seeking paths rooted in care and protection, to dance to the revolution.

For us, collectively figuring out how we want to live under radically altered climatic conditions means to firmly reject eco-fascist arguments that reinforce existing oppressions and falsely frame climate change in terms of scarcity.

Instead of doom and despair, we came to center conversations about solidarity, the redistribution of opportunities and resources from the few to the many, and to protect ‘joy and hope [as] the ultimate resistance to domination’. We came to examine the collective actions we need to reconnect and transform technologies, from a situated, decolonial, feminist perspective, towards justice and blooming, thriving communities.

Digital infrastructure isn’t just machines, it’s organic. More than just hardware and software, it’s community.

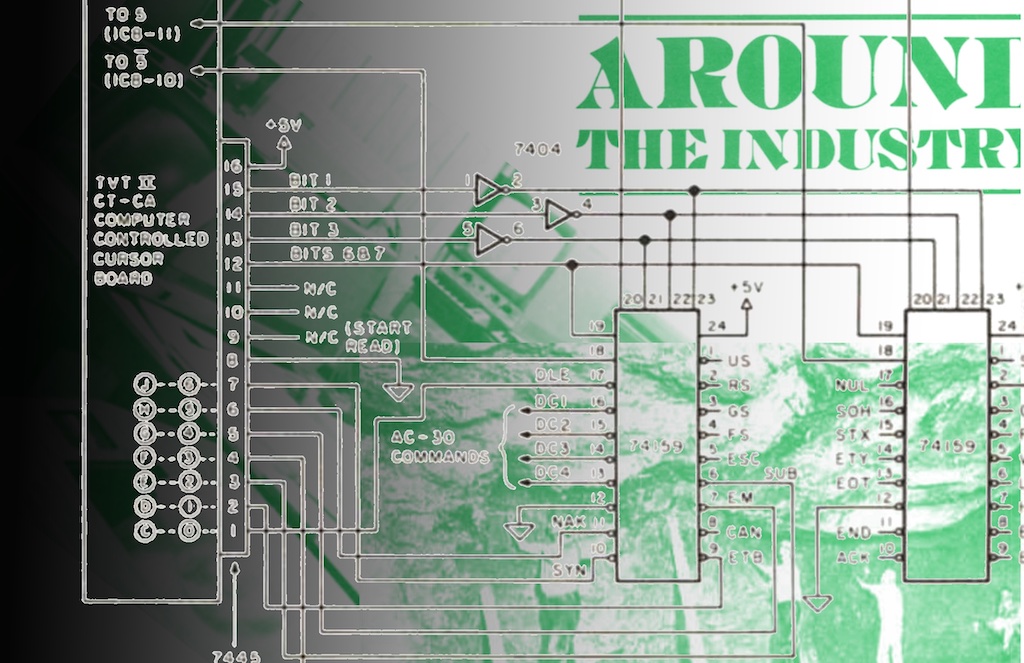

We arrived with a definition of digital infrastructure as the technologies and systems that form the backbone of internet access, and connect communities and applications. However, we were aware this was a porous and leaky definition. Today, digital infrastructures are ubiquitous. Hardly any social or commercial space is not shaped or affected by them in some way. This includes older infrastructures like energy grids and water supply systems.

While digital infrastructures can facilitate access to information, long-distance communication, organising movements, counter-mapping and monitoring by land and human rights defenders, they can also enable the coordination and execution of extractive activities ranging from financial speculation to mining and fossil fuel extraction. In either case, digital infrastructures provide the grounds on which people operate.

As we talked and listened to each other, we saw that, to build just futures, we would need to expand our definition beyond computing hardware, cables, and other physical objects, to the people who are designing, maintaining and inhabiting these infrastructures. This meant enfolding social and ecological relations – that is to say, the complex and intricate webs that create, sustain, and shape the worlds we inhabit.

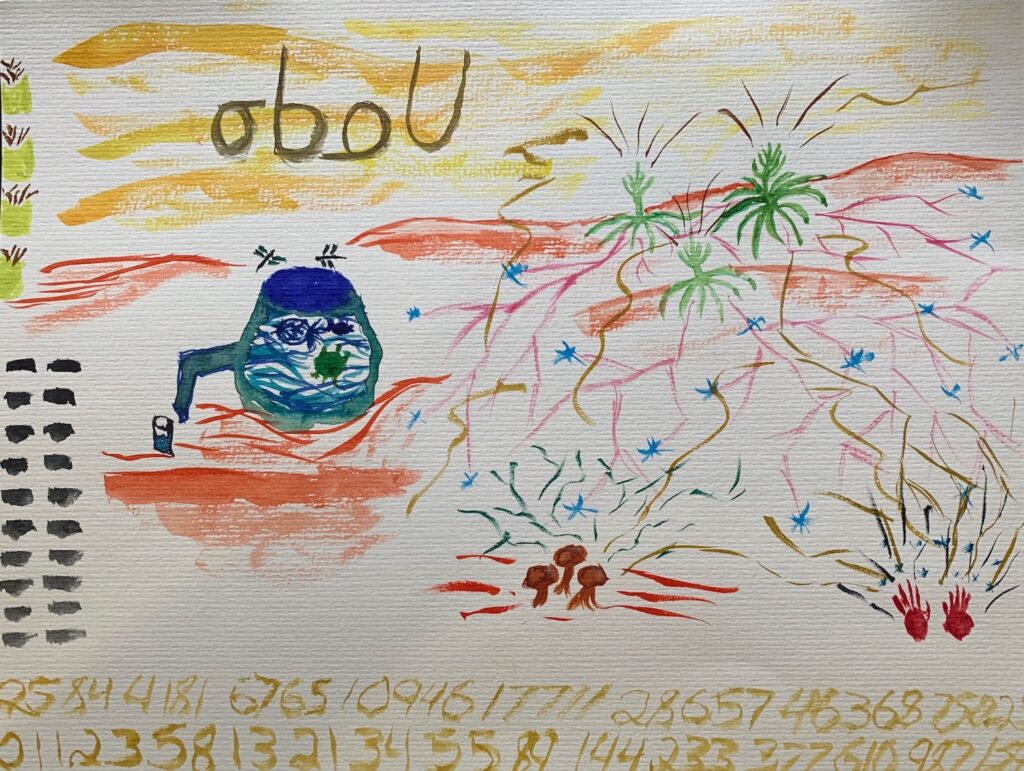

The image of diverse ancestral trees, grounded in different territories, whose intertwined roots are the infrastructure that sustains and influences the canopy (and vice versa), came to stand for individual infrastructures, and their collective interconnectedness. From this image emerged visions of a forest, a landscape composed of a patchwork of old and new, low-tech, lo-TEK and open-source digital infrastructures maintained as a shared responsibility with care and cariño (kindness). The forest is sustained to support resistance, heal and repair communities, affording both connection and disconnection. It is networked through feminist, border-less ties.

A forest centered in equity and sustainability

While widely used, ‘equity’ and ‘sustainability’ are not always clearly defined, and sometimes even hollowed out. For instance, ‘sustainability’ is often used by corporations and governments to greenwash their practices and products, while concealing the exploitation of labor and land to benefit capital. Drawing on the principles of future-making outlined above, the group’s conversations brought invisibilized labour and invisibilized harms within digital infrastructures to the forefront, and recognized how intricately-connected infrastructures are to the land and the relationships that nurture and maintain them, especially on a small-scale, local level.

One of the main points related to how we can rethink and rebuild connectivity beyond the extractive, privatized ‘Big Tech’ infrastructures that dominate our current moment. Power and resources were key to the conversation. Who owns, controls, and profits off digital infrastructures, and how might this power be reclaimed, distributed and integrated into local economies instead of benefitting CEOs and shareholders primarily in the Global North? How are financing mechanisms and organizational capacity for digital infrastructures shaped by global intellectual property law regimes and copyright? And how can these legal structures be challenged or suspended, especially in emergencies?

Our conversations showed that, in order to get to the futures we want, the communities that hold and sustain digital infrastructures need to be able to maintain them, and be acknowledged in co-responsibility for their labor. Crucially, they also need to be able to change these infrastructures or phase them out, have them die and become compost. This is easier when some of these infrastructures are based on natural materials, such as bamboo antennas, which also advantage community maintenance.

For there to be balance, transparency and equity should be at the center when defining who decides where infrastructures are (co-)located, how accessible they are, and their designed lifecycle.

It is difficult for smaller communities or worker cooperatives to own and run large physical infrastructures, like undersea cables or data centers. But grassroots groups can create, access and use free and open source software and set up peer-to-peer networks. This requires maintenance, necessitating the building of specialized capacities for these ‘homemade’, volunteer-run infrastructures, and the navigation of risks such as burnout and fundraising.

Tending trees, futures blossoming with hope

Today we celebrate initiatives around the globe that are seeding these desired landscapes and bringing them to life. Among the organizations and projects that inspire us are networks such as Rede Mocambos which organizes quilombola, indigenous, artist and artisan communities, the movement behind community data centers, indigenous-led streaming platform Nhandeflix, self-hosted and community-maintained mesh networks such as NYC Mesh and Freifunk Berlin, radio stations such as Noís Radio in Cali/Colombia, Sursiendo, the Alianza Mesoamericana de Pueblos y Bosques, the ‘Decolonizing Digital Rights’ initiative of European Digital Rights (EDRi) and the Digital Freedom Fund, the Numun Fund, The Engine Room’s support to organisations in justice-based technologies and data decisions, the Solar Media Collective, Rhizomatica, the Patio co-op network, the Local Networks (LocNet) initiative, participatory mapping tool Mapeo, the Design Justice Network, the project for internet services Tiwa (Instituto Nupef), the Traversal Network of Feminist Servers, and many others.

Capsules of our futures

It’s 2043. We honor the struggles and drive of the people who came before us, and those who will come after. We will tend the flame until we create the fire. Here you will find stories of built, created, disrupted and transformed digital infrastructures. Learn about our once speculative, now real, desired futures through them.

Capsule by Nathaly Espitia Díaz, Laura Aristizabal, Andrew Davis

Capsule by Andreea Belu, Jen Liu, Hanan Elmasu

Capsule by Jader Gama, Maya Richman, Rachel Smith

Paola Mosso is a cyber-feminist Latina activist and creative thinker, Co-Deputy Director of The Engine Room, where she grows the efforts on local support, community building and digital resilience of social justice movements. She works closely with feminist activists and technologists, and contributes to collective care practitioners and cyber-feminist communities. She enjoys playing with her dogs and collecting zines from local artists.

Janna Frenzel is a researcher, writer and communication strategist living in Tio’tia:ke/Montreal. Her research focuses on the environmental and social impacts of computing, and the role of extraction in the digital economy. Janna is passionate about vision building for more inclusive and just climate and technology futures. She also enjoys woodworking and making music.