Our glossy high definition screens glow brightly with coloured icons, buttons calling us to take action and tiled walls of vibrant photographs that look too good to be true. And yet despite the “perfection” presented to us online, there is something missing. There is a lifelessness to the modern web that seems inversely proportional to its refinement.

In contrast, the Japanese philosophy of Wabi Sabi is derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence, or ‘Sanbōin’, representing impermanence, suffering and the absence of self-nature. Wabi Sabi encourages us to accept and appreciate the imperfect and the transient nature of earthly things, finding beauty embedded into objects by the forces of nature.

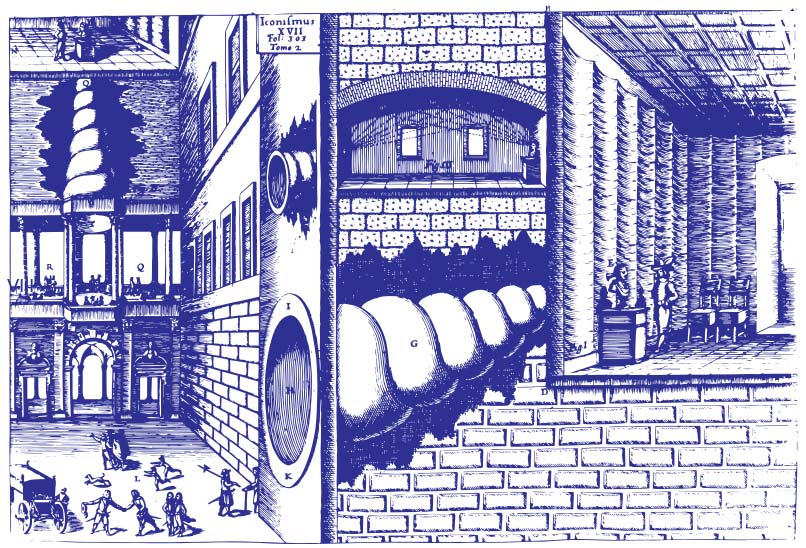

Many of the most beautiful things in life are those that carry their imperfections gracefully and tell us a story of where they have been, from the wrinkled hands of a grandparent, to the weathered walls of a building, to the subtle imperfections of a handmade mug or the patina worn into a piece of furniture that has been passed down for generations. These imperfections are infinitely complex, subtle and beautiful, yet impossible to replicate. It is the beauty of nature embedded into the fabric of our physical world.

There are a number of reasons why we humans find Wabi Sabi so special. We spend our lives running away from failure, decay and impurity, seeking freedom in the attainment of perfection. Yet, in one of life’s many paradoxes, when we finally achieve “perfection”, we find it to be flawed. Something deep down within us knows that everything is imperfect, and when we can’t see it, it’s as though something is being hidden from us beneath an artificial veneer. While we may be intoxicated by apparent perfection, we simultaneously fear that it may be too good to be true.

So-called perfection also plays on our subconscious by eliminating the motivation to improve. The challenges of life are illuminated by the constant pursuit of improvement, as we strive to evolve ourselves and the world around us toward a better future. While we strive for perfection, the joy of its attainment is often followed by a vast emptiness and loss of purpose. Wabi Sabi’s beauty rests in its ability to dance close to perfection, but not too close or for too long.

Furthermore, our natural world is infinitely rich and diverse with sounds, textures, smells and the constantly changing dance of light across the landscape. When we’re in a natural environment, all of our senses are deeply stimulated with so much variety and detail that it could never be artificially replicated. Our mass produced goods and digital worlds may be glossy, but cannot come close to the depth of sensory stimulation provided by the natural world. Just as refined foods give us a quick high but leave us lacking the nourishment of the whole, so too does the digital world lack the wholesome stimulation that our bodies and minds crave. Likewise, when we walk around a museum, the perfectly smooth and flat marble floors should be easy to walk on, but in fact, are exhausting due to their lack of variation. The modern world of digital appears easy on our minds, yet is exhaustingly uniform and repetitive.

And then there is the final reason, which is that Wabi Sabi tells a story, through the textures and imperfections that build up over time in physical objects. We see the history of where they have been and the lives that they have touched. There is a subtlety to the ability of natural materials to tell stories that warm our hearts and spark our imaginations. Our digital worlds, on the other hand, behave in a binary manner, jumping from perfect to broken in a flash without any narrative of their journey.

It’s clear to me that as humans, we need an environment that holds these magic qualities of Wabi Sabi and yet the digital world that we spend an increasing proportion of our lives inhabiting, seems inherently free of it. Could it be possible to create a web that is more fulfilling, healthy and natural if we embraced the beauty of imperfection and impermanence in our digital worlds, in a Wabi Sabi Web?

Let us imagine some ways that we could potentially bring some of the wonder of Wabi Sabi into our digital world.

Scratching the surface

- Embrace texture – In contrast to some of the early web, it’s become the norm of websites and digital services to have mostly plain block colours, free of texture. While we must be considerate of accessibility, the possibility of infusing our digital worlds with subtle textures that follow non-linear patterns (as oppose to repeating tiles) could be an exciting creative challenge for designers and developers alike.

- Remove the polish – Much of the imagery we see online today, particularly through social channels, has been framed and filtered to remove imperfections and create a standardised aesthetic. We could be more confident with our photographic styles, embracing the Wabi Sabi qualities of our subjects and emphasising, rather than hiding, the imperfections in the photography and video that we bring to the screen.

- Break the grid – In contrast to the early days of the web that were scrappy and imbued with individual creativity and its inherent imperfections, modern digital design tends to follow standardised grid layouts. This is often motivated by a desire to create simple user experiences while also making lives easier for developers, but it can also eliminate variety and contribute to the monotony of the digital world. By using grids and design patterns as suggestions rather than rules, we can explore opportunities to create more organic and unique experiences that are just as easy to use but more beautiful, more interesting and more stimulating.

- Create some patina – Unlike the physical world where objects weather over time, the digital world is always the same (unless it’s broken). This might seem like an inherent limitation of the digital medium, but perhaps it isn’t. We could explore possibilities to add patina to our digital designs that build up as people interact with our experiences, or elements that weather with time, such as images discolouring based on the amount of time they have been online. We must be careful not to get carried away with gimmicks that consume a lot of energy or slow down people’s devices, but there are no doubt many creative opportunities to enrich our digital world.

Being human

- Use our hands – While the surfaces on which we view digital services are inherently flat, square and smooth, the content that we display on them need not be. Instead of relying entirely on computer drawn graphics, we can create more artwork by hand using traditional techniques. We will inevitably lose some of the magic in the process of digitisation, but by starting in an analogue form we can bring more of the magic onto the screen. We could even create more organic fonts based on the handwriting of real people.

- Be more honest – It’s not just the visual aesthetic of the digital world that is artificially glossy, but the content too. By putting our true personalities into content, including our rough edges and honest mistakes, we can create content that feels more natural, enriching and rewarding. It takes confidence to create truly honest content, but in a digital world increasingly dominated by the voice of AI, there is even greater opportunity to let our human voices shine. We can also increase opportunities for people to make contact with a real human, whether it’s using humans instead of bots for live chat, making it easy for people to phone us or encouraging the arrangement of in person appointments. Our digital services could be the enablers of increased human interaction instead of being the barriers.

- Let people explore – Modern user experience design includes concepts like planned user journeys and “funnels” to guide people to a destination, and while these can be useful techniques, they limit the creative scope of the visitor to follow their own path of exploration. What would happen if we also designed experiences with the aim of encouraging exploration and variety in the way we navigate and digest content online? Furthermore, instead of using algorithms to personalise content, we could explore opportunities for people to customise and curate their own experiences to truly suit their needs.

- Leave the screen behind – Augmented reality experiences attempt to blend the real world with the digital world, but push the users attention into the device, downgrading real world experiences. We could try to flip this concept on its head, designing digital experiences that encourage people to leave the screen and tune back into the world around them, whether it’s by asking them to close their eyes for a short meditation or get up from their seat to find the real plant that they are learning about online.

Passing time

- Vary the pace – While breaking the grid can help us to create variation in space, we could also explore variation in the fourth dimension – time. It’s generally assumed that speed is inherently good in the digital world, but mindful variation of pace can create richer and more fulfilling experiences. This could be achieved by giving the user opportunities to vary the pace to follow their own ebb and flow, or by consciously designing elements that encourage people to vary their pace as they move through an experience.

- Embrace endings – The digital world is all about exciting beginnings, from hitting send to a message, publishing a new piece of content or launching a new website or app. But what about the endings? We should think about the full life cycle of digital content and services, embracing their impermanence so that they gracefully fade away when no longer needed. Consider scheduling content to stay live only while it is relevant, clearing out old data that is no longer needed, or decommissioning digital services that would otherwise have stayed online indefinitely. Embracing impermanence can help us declutter the web and reduce its environmental impact too.

- Reveal history – The binary nature of the digital world tends to appear to us as if things were always there in their current form, in contrast to the changing dynamics of nature whose history is written into the materials themselves, showing the wear and discolouration of their interactions with humans, animals and the elements. We could bring more of this into the digital world by revealing more of the meta data and version history of our services in a way that is engaging and accessible to the end users, not just the developers behind the scenes. We could even get creative and use historical data of a website’s past to generate a visual patina that tells a story through texture.

These are just a few suggestions, and in the spirit of imperfection I acknowledge that this list is inherently incomplete and that each idea is imperfect. I hope though, that they provide some inspiration to get us started in bringing the beauty of Wabi Sabi into the digital world. We know that our lives are becoming increasingly digital and we know how much we need and love the rich beauty of the physical world, so good digital design must surely now include exploration of the Wabi Sabi Web.

Tom Greenwood is the co-founder of Wholegrain Digital and is known for writing and speaking about how business, design, and web technology can be part of the solution to environmental issues. He is author of the book Sustainable Web Design, the green web newsletter Curiously Green and the sustainable business newsletter Oxymoron.