Connectivity & Sensation

What does the internet feel like? This idea fascinates me. About five years ago, I asked the internet for its opinion; and over the years, I have been slowly accumulating an eccentric blend of responses, such as:

“[like] holding hands with a stranger”

“mesh-y”

“the surface of an ice cube, but also not cold, more like lukewarm”

“smooth like rubber”

“like grass”

“polar”

“used to be [a] mountain but lately more like tropical”

These responses are geological and biological in nature, and they capture the human tendency to make sense of the world through material relations and sensory experience, even in virtual forms. So, in this age of digital ubiquity, when connection is qualified by a lack of friction and quantified in processing power and upload/download speed, it is important to consider the attributes of connectivity. As Marshall McLuhan observed 60 years ago in his book Understanding Media, the character of a medium can easily be overlooked. He says, “it is only too typical that the ‘content’ of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium”, as it shapes and controls “the scale and form of human association and action”. So, what exactly is a good connection, and what might we be missing in the quest for instant and infinite access to content and communication? And, if the current state of the internet seems good for you, is it also good for the planet? If not, then can it actually be good for you? We don’t exist outside of the natural systems that shape and sustain us, so what stability can come from pretending otherwise on an industrial scale? As Donna Haraway puts it in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, “We require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become – with each other or not at all.” So, how might considering the internet as a physical experience help us design a more sustainable, equitable future?

In recent decades, there has been a condensation of metaphorical language comparing the infrastructure of our vast communication networks to clouds. One of the consequences of this clever marketing trick is that, while online experiences do evoke sensations, the materiality of the internet and its content predominantly remains outside of our awareness and sensory field of being – our umwelt — beyond our immediate line of sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste. This limits our ability to relate to information and cultivates a disembodied worldview. Unless, perhaps, you are working as a smelter or living near an electronic waste dump, as charted by Kate Crawford and Vladan Jole in their brilliant “Anatomy of an AI System”, there typically exists a geographical gulf between the environmental relationality of online life and a user’s surroundings. However, there is a growing body of community-led projects that inspire a different way of being digitally connected in a more-than-human world.

Embracing Constraints

Projects like Solar Protocol, LOW←TECH MAGAZINE, and the Potato Internet blend speculative design, DIY methodologies, ecological thinking, science, art, and technology to subvert expectations and explore possibilities for real change. They work within the material realities and limitations of the natural world, allowing conditions like sunlight, distance, and mineral composition of plants to serve as tangible design constraints, conjuring new imaginaries for what being connected could mean. These alternative approaches are more prone to disconnection than our current digital communication frameworks. The tagline at the top of LOW←TECH MAGAZINE is explicit: “This is a solar-powered website, which means it sometimes goes offline.” This friction contradicts the expectations of seamless online experiences that characterise contemporary mainstream interactions on the internet, as do the lo-fi aesthetic qualities. Rather than funnelling energy and resources into enhancing slickness, constraints are, crucially, embraced as design opportunities.In doing so, these styles embody the beauty of what a different kind of connectivity could feel and look like. Minimalist design patterns rooted in the energy demands of data transfer and rendering take shape in the form of image dithering, simplified colourways, and default system fonts. When approached as a design opportunity to embrace instead of a challenge to hide, these aesthetics become something new and powerful, extending well beyond a stylised nostalgia for a GeoCities web of yesteryear.

Solar Protocol (http://solarprotocol.net) advances this philosophy further in a white paper that blends art, web development, human computer interaction (HCI), and artificial intelligence (AI) to outline an Energy-Centered Design practice. This unique approach scrutinises, examines and explores ways of reducing the energy demands of networked technology while providing an operational alternative to being connected online. Placing solar-powered technology at the core of its design, the network operates with the intelligence and logic of the sun, providing connectivity via whichever server has access to the most sunlight and thus energy. Like LOW←TECH MAGAZINE (https://solar.lowtechmagazine.com), it minimises the amount of data being transferred by reducing the file size and fidelity of media that is being transferred. This aesthetic is not a veneer. Its beauty, and power, exists in what it embodies.

Projects like these can empower our collective imagination. They give us opportunities to fabricate alternatives to the current internet, which relies on an energy regime enabled by the overconsumption of fossil fuels – with severe effects. However, things don’t have to be this way. Sure, it has never been so emotionally convenient for humans to consume and exchange information. But what about the costs of this immediacy? If our current internet model – and its data-reliant appendages like artificial intelligence (AI) – run on electricity, we will need more electricity to keep it running. This also means that we will need even more electricity to continue feeding this massive, data- and energy-hungry beast. However, considering the planetary boundaries, is it worth questioning whether this system needs to continue to grow? And if so, why? Do we need fossil fuels to power this system, or are there ways to design the whole system differently? Could it work more sustainably and – dare I say – better?

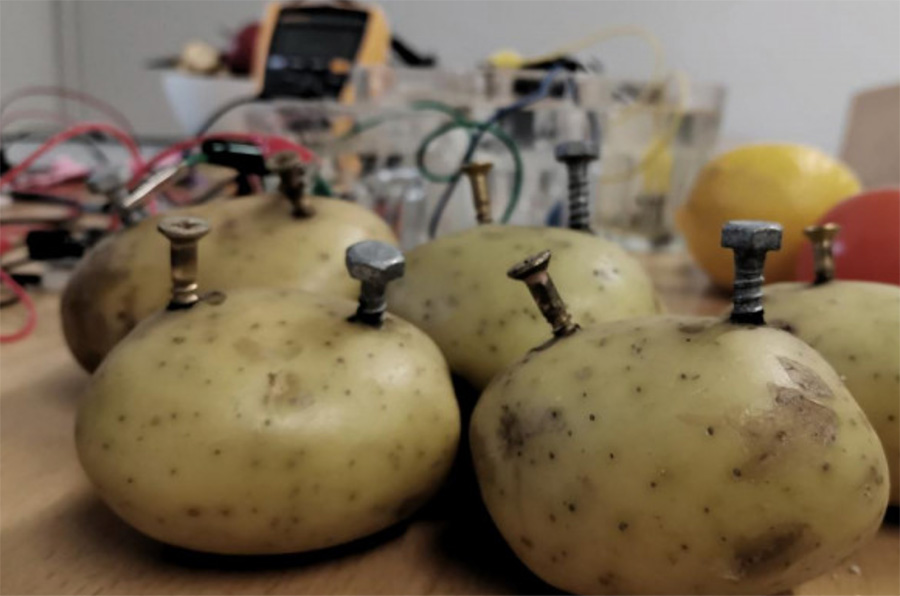

Scalability of these networks is not a central goal, and none capture this spirit better than the Potato Internet (https://potatoes.network). A self-described provocation, ephemeral technology, and community, it exists as “a small scale social network, powered by a raspberry pi mesh network system and potatoes, that updates only once or twice a day.” The impetus for its creation being the necessary desire to “reimagine the internet in times of climate emergency.” Here, the issue of scalability, a standard part of criticism from mainstream perspectives, holds exciting creative potential and value worth embracing. A future that scales down instead of up might afford us an opportunity to build “a functioning social network from scratch, rethinking all layers of the system, from hardware to protocols and governance.” To begin reflecting, asking questions, and reconsidering our expectations about why things are the way they are is a vital step toward reimagining a more equitable, healthy, connected future for humans and our more-than-human kin. Like good art, these projects provide the experience and space to reconsider expectations. Would it really be so bad if your connection ran out of energy before you took in one more meme, streamed one more episode, or scrolled through your feed for another ten minutes? Convenient now? Probably not. Convenient later? Maybe. Convenient for the planet? Absolutely.

Intermingling

These alternative networks operate with a kind of critical connectivity, providing fresh and timely takes on digital connection in an era of climate crisis. Like their cybernetic forerunners, they are an assemblage of disciplines, combining art, engineering, science, computation, design, and more. This transdisciplinary intermingling of human skill sets combined with the more-than-human aesthetic potential conjures Anna Tsing’s notion of contamination as collaboration. The indeterminate outcomes of these experimental networks are bound together in a web of interdependent relationships essential to its survival. There is an intelligence in the more-than-human world that needs heeding; and if “intelligence is the capacity to synthesize knowledge as logic and apply that logic to make decisions”, then there is great creative potential, and need, for remembering what can emerge from consciously designing from within earthly dynamics. What would a future feel like if we designed solutions borne from the challenges of harnessing the energy of edible tubers? After chuckling, it’s still worth imagining. The poetic potential of being connected by sunlight taps into a biological, geological, and cosmological imagination. Technologies designed to balance the seasonal ebb and flow of foliage with the planetary tilt and rotation of Earth could operate with an internal clock set to tree time. What would that internet feel like?

The projects I’ve highlighted demonstrate ways of putting community values at the core of technology, and I recommend checking them out. There are guides and resources available if you are looking to explore this kind of connectivity further; and if you are curious about a lively alternative to social networks, a platform like are.na is a great space to spend time. Aiming to be a place of “utility, health, and happiness”, its values direct governance, roadmapping, development, and design. While the constraints of natural resources aren’t its central tenet, it promotes a garden’s pace and ethos far removed from functionally similar mainstream feeds. For more than a decade, it has been evolving along the internet substrate with a kind of mycelial intelligence. New people and communities join, contribute ideas and information, and form new knowledge and connections driven by genuine curiosity and interest. Mainstream monetary mechanisms like click rates don’t dictate value and platform experience. This allows for a kind of organic growth that is all too rare in the content marketplace of today’s internet. At times, it might seem easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of the current internet. But these projects – and many others like them – beautifully counter that notion, simply by existing. They provide the ferment for possible futures worth cultivating. The truth is that the mainstream, one-size-fits-all approach for a universally scalable, fossil-fuel powered planetary network is a monocultural approach to communication technology. The model strives for sanitation when what we really need is more contamination – more options for how we connect with each other and the world. I hope that after reading this, they are a little easier to imagine.

Jesse Thompson is a London-based, American-born artist, designer, and musician exploring how meaning is made through sensory experience, computation, community, and interaction with the more-than-human world. He is currently a lecturer in the Design School at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London.