This article seeks to uncover the relationship between issues of Internet connectivity and infrastructure in the Amazon, which is essential for the political mobilisation of the peoples who live there, and the large extractive projects that threaten the ecosystems and socio-biodiverse territories that exist there. While a large part of the region’s population has poor internet access, predatory extractivism manages to connect to the network efficiently.

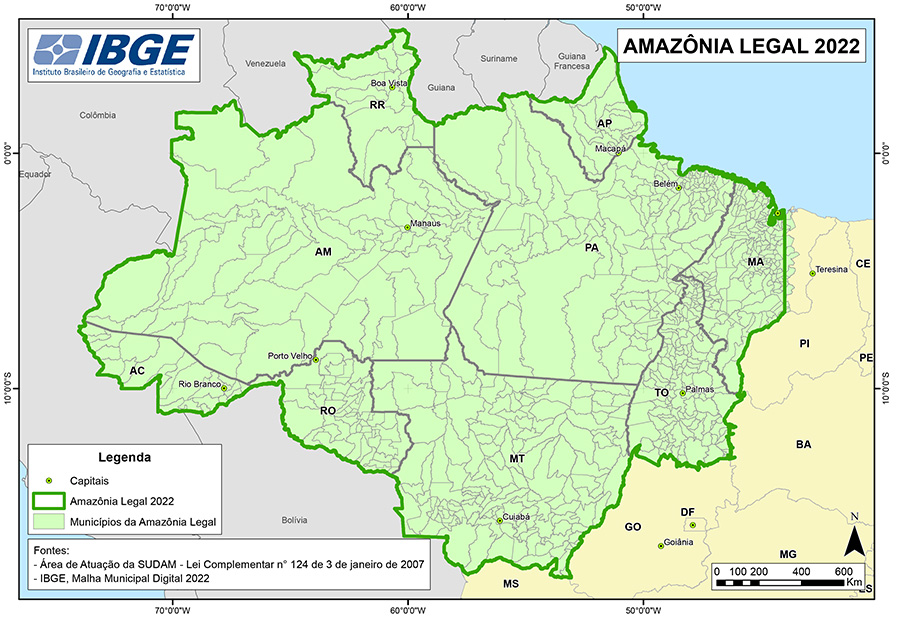

But who makes up this population? According to data recently released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) based on research carried out for the 2022 Brazilian Census1, the North Region has 17.3 million inhabitants, around 8.5% of the country’s total population. The region, together with the states of Maranhão and Mato Grosso, make up the geopolitical region known as the Brazilian Legal Amazon2.

Among other data revealed by the survey, we can highlight that the North Region also has the highest percentage of people who call themselves Pardos in Brazil, with 67.2% of the population. Pardos are people who identify with a mixture of two or more colour or race options in the survey, such as white, black or indigenous3. The same survey reveals that the North concentrates 44% of Brazil’s indigenous population and 32.1% of the quilombola population (made up of descendants of blacks who fled slavery and took refuge in places called quilombos).

These populations, who experience a different relationship with nature and the land in contrast to the Western way of life, live with constant threats to their territories and ways of life from organised crime or even large business or government ventures that cause devastating environmental impacts on their ways of life.

Promoting Internet access has received the attention of public managers, third sector organisations and large telecommunications companies in Brazil over the last 30 years. Commonly referred to as ‘Digital Inclusion’, guaranteed access to the net has become a prerequisite for access to public services and basic rights, as national and local governments have begun to digitise their processes. Here we start from a concept of digital inclusion that goes beyond the dualism between inclusion/exclusion, promoting human rights, citizenship and the dynamics of generating new rights linked to digital, seeking social transformation.

Connectivity and the defence of the peoples of the Amazon

Internet access has become a prerequisite for guaranteeing social rights and full citizenship and, at the same time, a tool for denunciation, playing a leading role in defending the indigenous and traditional peoples of the Amazon and their ways of life. These populations have organised and articulated themselves politically to strengthen their communities and causes, acting in mobilisation networks that cross geographical spaces and inspire social change.

According to data from the “ICT Households 2023” survey4 by the Regional Centre for Studies on the Development of the Information Society (Cetic), linked to the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI.Br), 85% of Brazilian households have some kind of internet access in 2023, an increase on previous years’ surveys that sought to measure the same data. ICT Households 2015 indicated that only 51% of households had access to the network and ICT Households 2019 found that only 71% had some form of access.

Regarding the North Region, in which all the states belong to the Legal Amazon, the survey indicates that 79% of households in the region had internet access in 2023, an increase from the 38% recorded in 2015 and 72% in 2019. These figures show that Brazil, and also the states of the Amazon region, are moving towards universal access.

But this panorama of growing access to ICTs can mask deficiencies in the quality of this connectivity. The recently launched study “Significant Connectivity: Proposals for measuring and portraying the population in Brazil”5, also by Cetic, assessed Internet access in these households based on indicators grouped into the dimensions of affordability, access to equipment, connection quality and usage environment. The study created a scale of 0 to 9 of significant connectivity for the Brazilian population.

Measuring the quality of internet access, the study found that only 22% of the Brazilian population is in the group with good quality internet access, while 33% are in the worst group. Among the nine states of the Legal Amazon, the ones with the highest percentage of households with quality connectivity are Rondônia, with 18.7%, Tocantins, with 17.9%, and Acre, with 13.4%. Among the states with the highest percentage of households with poor connectivity are Roraima with 55.3%, Amazonas with 48.5% and Maranhão with 48.3%. The North Region, which includes 7 of the 9 states of the Legal Amazon, has 11% of households in the good connectivity group and 44% in the poor quality group.

This study also found that the lack of infrastructure in remote and sparsely populated areas, such as rural areas, reduces the interest of companies in offering internet access, which explains part of the asymmetries between the different regions of the country.

The Covid-19 pandemic, which has shifted much of the access to education, health and social assistance to the internet, has led part of the population to start looking for ways to access the web, even if precariously. But the use of communication and the internet, even with poor access, as a way of mobilising social movements in the Amazon has been going on for much longer than that, as a form of struggle. It is in this context that the Centro Popular de Comunicação e Audiovisual (CPA)6, an organisation based in the city of Manaus and of which I am a member, was founded in 2016, seeking to promote training and debates on communication practices that promote the rights of different populations, whether they are considered urban or rural.

Throughout 2023, our collective took part in various events and promoted debates on meaningful connectivity, digital rights and socio-environmental justice, always presenting these complex issues from an Amazonian perspective. Among the consolidated efforts, the collective produced, together with the Pan-Amazonian Technopolitical Coalition, the Letter of Recommendations for Digital Policies in the Amazon7.

And yet, in the midst of this precarious context, these populations continue to exist and resist the advances of the various extractive activities that threaten them. In an attempt to unravel these relationships, I have gathered here some data collected by researchers and organisations working in the region, showing cause and effect relationships.

Connectivity x Extractivism

These processes of connectivity in the Amazon are crossed by other territorial issues. Historically, the region has been controlled more by geopolitical sovereignty strategies than by settlements and occupations. Another characteristic is that development has been realised through economic cycles of expansion, alternating with periods of decadence and neglect. Since colonial times, the Amazon has been seen as a periphery of capitalism, where the development model is based on the continuous exploitation of land and natural resources and the marginalisation of its inhabitants.

Because of this continuous exploitation, indigenous and traditional peoples are under constant threat from the region’s major undertakings, often the result of initiatives by governments, companies or even criminals attracted by the rich natural resources.

To this day, the Amazon is still seen by many as a wild and uninhabited territory, devoid of and disconnected from civilisation. In her book The Invention of the Amazon8, Professor Neide Gondim explains that this understanding, which has displaced the efforts of different actors and initiatives in the region to achieve progress and financial development, stems from the European idea of an exotic Amazon, full of mysteries and resources, which dates back to the mid-15th century. This labelling of what is meant by the Amazon, through foreign eyes, prevents its populations from thinking about their own development and aspiring to their own model of progress.

The link between internet connectivity and colonialism

At the same time as this imaginary marginalises the inhabitants of these territories, it indicates solutions to their social problems from outside, promising to include them in society and in the productive flows needed to produce wealth. Among the many promises of this development, the internet arrived in the Amazon territories as a technological solution to overcome the supposed isolation of the people who live there. But Internet access in the region has always been unstable , both inside and outside urban areas, as indicated by the study “Internet Access in the North Region of Brazil”9, conducted by the Brazilian Institute for Consumer Defence (Idec), which points to poor infrastructure and abusive commercial practices.

In the article Connection infrastructures and the cyberactivism of black women in the Amazon10, published in the CGI.Br collection ICT, Internet Governance, Gender, Race and Diversity, the authors reflect on the Internet connection infrastructures installed in the Amazon and make a comparison with the predatory extraction infrastructures within the territories. They also analyse the fact that even the development projects of the private sector and the Brazilian government, such as hydroelectric dams, operate in the region under a colonial logic.

The article discusses how hydroelectric dams, which have a major socio-environmental impact on the Amazon, supply electricity to the whole of Brazil, while Amazonian cities and regions suffer from an unreliable electricity supply. The same electricity transmission lines are capable of distributing internet access points, due to the fiber optics present in them, but this potential is not used to bring the internet to the region, except in the case of large, corporate projects in the region.

Beyond what the article discusses, it is not difficult to find reports of these relationships between the internet connection and extraction infrastructures that cross the Amazon region. In 2022, an article published by Reuters revealed an investigation11 into how gold extracted illegally in the Amazon was being passed on to Europe by an Italian company that was on the list of mineral suppliers to companies such as Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Alphabet.

In another example, the Brazilian press reported that federal police operations to combat illegal mining in the Amazon had found aerials belonging to the company Starlink during seizures against criminals12. The journalists’ investigation indicated that 20 antennas or routers belonging to the company had been seized over a period of one year.

It is undeniable that connectivity is a necessity for the people of the Amazonian region, but the instability of the internet access infrastructure makes it difficult or impossible for them to connect. On the other hand, the territories in which they live are affected by well-functioning predatory extraction infrastructures.

Connecting other ways of life

Internet access is a possible tool for the struggle to fight for the rights and exercise the citizenship of the indigenous and traditional peoples of the Amazon. Access to the web makes it possible to communicate from the territories, both in the production of denunciations and in the dissemination of their ways of life. But the region’s unique history and the way in which connectivity infrastructures are made available make this use uncertain.

These relationships between poor connectivity infrastructures and the threat of extractive infrastructures are ambiguous and reflect the expectations that large business groups and different governments have of the Amazon. These expectations differ from those of local traditional populations, who seek better living conditions and respect for the nature they live in harmony with.

It is clear that the technical and commercial justifications for the difficulty of providing these infrastructures are part of an intentional process that excludes the Amazon and its populations from access to the network. At the same time, this process does not exclude the large enterprises and extractive activities that cause significant environmental damage in the region. The challenge for the coming years is to ensure that the significant connectivity of the region’s population improves and that access to the network is better distributed, especially to the traditional and indigenous populations of the Amazon.

Access to the network is paramount to guarantee the integrity of these peoples and their ecosystems, but the solutions will not be readily offered by the extractivism and connectivity companies operating in the region. They need to come from the collective discussions and agreements among the people who live in these territories as they understand the needs and social-environmental wealth of these places.

The political mobilisation of the local population to make these situations visible and denounce them is essential to guarantee digital rights and environmental justice in the Amazon territories. This is a strategic region for cultural diversity, the sustainable management of natural resources and the climatic well-being of the whole of South America. The voices of this region must be heard and strengthened in order to guarantee these local balances that influence the entire world . Protecting these communities and their biodiversity is crucial, as it supports a future that relies on ancient wisdom to address and solve today’s shared challenges.

Hemanuel Veras is a journalist from Manaus, the capital of Amazonas. He currently lives in Rio de Janeiro and is studying for a PhD in Communication and Culture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He is a member of the Popular Communication and Audiovisual Centre (CPA) and the Internet Governance Research Network (REDE).

- https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/panorama/ (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- The Brazilian Legal Amazon is made up of the states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, Roraima, Rondônia and Tocantins. More information can be found here: https://www.ibge.gov.br/en/geosciences/maps/regional-maps/17927-legal-amazon.html ↩︎

- https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-detalhe-de-midia.html?view=mediaibge&catid=2101&id=6890 (Audio in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- https://cetic.br/pt/pesquisa/domicilios/indicadores/ ↩︎

- https://cetic.br/pt/publicacao/conectividade-significativa-propostas-para-medicao-e-o-retrato-da-populacao-no-brasil/ (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- https://cpa.org.br/ ↩︎

- https://cpa.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Carta-de-Recomendacoes-para-Politicas-Digitais-na-Amazonia.pdf (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- https://www.amazon.com/inven%C3%A7%C3%A3o-Amaz%C3%B4nia-Portuguese-Neide-Gondim-ebook/dp/B0CM7VTFZF?ref_=ast_author_mpb (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- https://idec.org.br/arquivos/pesquisas-acesso-internet/idec_pesquisa-acesso-internet_acesso-internet-regiao-norte.pdf (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- https://cgi.br/publicacao/3-coletanea-de-artigos-tic-governanca-da-internet-genero-raca-e-diversidade-tendencias-e-desafios/ written by Geiza Silva, Gustavo Souza and Thiane Barros, pages 147-185 (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎

- https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/illegal-brazil-gold-tied-italian-refiner-big-tech-customers-documents-2022-07-25/ (ENG) ↩︎

- https://noticias.uol.com.br/cotidiano/ultimas-noticias/2024/04/12/ibama-apreende-antenas-starlink-internet-elon-musk-garimpo-ilegal-amazonia.htm (in Brazilian Portuguese) ↩︎