Michael Oghia is one of the leading voices getting sustainability on the agenda of Internet governance and digital rights communities. He encourages us to see the interconnectedness of environmental sustainability, human rights, and climate change—which are all inextricably linked to the Internet.

We can probably all agree that 2020 has been a rough year. If it has taught us anything, though, is that everything on this planet is inherently interconnected. While globalisation, viral outbreaks, or national crises are hardly novel, the fact is we now have a stark and sobering understanding of how, for instance, a farmer with a cough in one part of the world can have a significant and consequential impact on a shopkeeper in another. It’s unclear what lessons we as a collective will draw from this or what the long-term impact will be—a recent Radiolab podcast traced how the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic left the world permanently transformed—but one thing is certain: “everyone for themselves” will be our undoing.

The same logic that applies to the pandemic we’re living through extends to a much bigger and undoubtedly even more impactful global event: the climate crisis. Carbon emitted in one part of the world affects another (often disproportionately those in less developed countries); yet, it’s clear we all suffer the consequences if the climate becomes inhospitable.

When it comes to information and communications technologies (ICTs), similar principles apply to our global footprint. The growing demands of an Internet-dependent and interconnected society are contributing to unprecedented levels of energy consumption, conflict mineral mining, electronic waste (e-waste) generation and its subsequent dumping in some of the most impoverished communities, climate change, and negative effects on vulnerable natural landscapes and marginalised communities around the world. And just as the contributing factors are interlinked, so are the impacts.

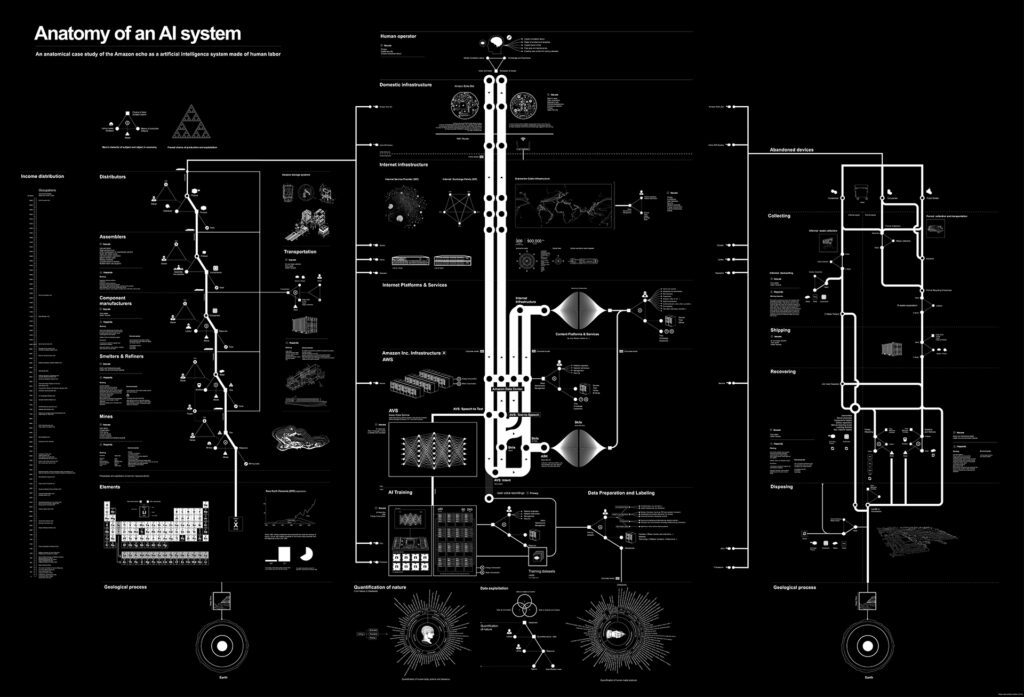

Last year, when I still had the ability to venture beyond my living room, I visited an art exhibition in Vienna as part of a conference I attended. There was one installation that particularly struck me: the Anatomy of an AI system.

The artists, Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, illustrated this predicament well using an Amazon Echo in what they call “an anatomical map of human labor, data, and planetary resources.” By deconstructing a single piece of technology into its subsequent parts, it visualises not just how interconnected our digital world is but also its connection to the natural one. After all, although it’s easy to preoccupy our focus on the “cyber” in cyberspace, it has to exist somewhere. That “space” isn’t just a Reddit thread, software protocols, or a wiki, but a data centre, energy being consumed to create an iPhone, the cables and wires that connect continents, and even the satellites orbiting the Earth beaming the signals. To divorce the two is impossible; both our technology and virtual spaces mirror real life because they are real life. And just like how disinformation wreaks havoc online, our virtual habits reverberate offline through the environment as well.

Building a better Internet

As I’ve underscored in the past, sustainability is in many ways a fundamental yet unwritten condition of modern democracy, not least because it is so intimately intertwined with inequality and access to information. Both are critical links to education and democracy, and tools like the Internet help facilitate the functions of citizenship that are meant to empower populaces and hold elected officials to account. And although the ability to participate in society online promotes social inclusion, many are still excluded from digital citizenship. In fact, access to information via ICTs is fundamentally uneven, especially across the Global South.

Sustainability is…a fundamental yet unwritten condition of modern democracy, not least because it is so intimately intertwined with inequality and access to information.

It’s easy to get caught up with grand visions of future outcomes, but the real emphasis should be on the process. At the heart of this are the communities that are ultimately being impacted, and the reality that we cannot legitimately discuss Internet access and the kind of Internet we need to build without addressing sustainability. In 2017, I posited that we should prioritise a new framework to address the inequality that exists online, one that places particular emphasis on fostering “sustainable access” – the ability for any user to connect to the Internet and then stay connected over time. As of writing, just over half of all people in the world are connected to the Internet, while more than 3.5 billion don’t have access to reliable electricity (and just under a billion don’t have access to electricity at all). How do we expect people and communities who aren’t even wired to electrical grids to participate online in languages they likely do not speak or with a device that, if they can access and afford, cannot even be charged properly?

When imagining the actual Internet of the future that we need, it’s necessary to discard some of the fantasies of science fiction. The future of the Internet for billions around the world, particularly the unconnected, isn’t virtual reality or self-driving cars. It’s low-powered websites populated with content in local languages and mobile data plans that someone living on less than three euros per day can actually afford to use so they can talk to far-away relatives and get the latest weather reports vital to their livelihoods (such as whether to go to the market that day, or plant a field). But taking into consideration the needs of the most vulnerable requires the most vulnerable. Making the Internet more inclusive is not impossible, and there are many hurdles to overcome, but amplifying such voices and recognising the holistic nature of digital inclusion is crucial.

The future of the Internet for billions around the world, particularly the unconnected, isn’t virtual reality or self-driving cars. It’s low-powered websites populated with content in local languages and mobile data plans.

How do we get there?

Where do we go to bring all the elements together? What mechanisms exist so that we can, for instance, address data sharing and privacy protection when discussing the best ways to integrate the various smart solutions for better energy management, but also collectively safeguard the gorillas that are going extinct due to the minerals – mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and neighbouring countries by conflict labour – that are used in the devices that make smart solutions possible?

These problems are so multilayered and span so many domains that it’s imperative that we work on them together—no matter whether you’re a developer, an engineer, an activist, a policy wonk, a marketing manager, or anything in-between. Just like me, you don’t necessarily have to be a “technical person” to advocate for meaningful change (though you most certainly can if you are). On the contrary, we each have a role to play, and collaboration has never been more dire. The way to do it may well be through the existing processes and fora of Internet governance. Multiple parallels already exist between efforts to manage and regulate the Internet and the efforts to mitigate climate change. Both rely on expertise drawn from multiple sectors to generate any kind of meaningful outcome (known as the multi-stakeholder model), and both seek to address challenges that transcend national borders and a one-size-fits-all solution. They are intrinsically connected, if not by subject, then by structure.

And it’s not like there aren’t communities to draw from to speak to the nexus of issues that intersect technology, the environment, and human rights either. From the academically focused ICT for Sustainability (ICT4S) community, to the network of professionals working on the circular economy, there is ample expertise to help shape such important policy discussions. In fact, in my experience, there is plenty of intra-community discussion and sharing on this topic, however, inter-community knowledge exchange is practically non-existent. Other than some useful, but ultimately ad hoc events organised here and there, there is no systematic approach to addressing ICT sustainability in a more holistic, collaborative, and inclusive way.

Instead, most sustainability-related issues—from energy use to e-waste dumping—are addressed in a “siloed” approach, that is, in a more piecemeal and narrow way. There’s no specific venue, no dedicated multi-stakeholder forum, not even a mention within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an overlook I’ve heavily criticised. This is not only ineffective, but it completely ignores the interconnectedness that exists between engineers and designers, supply chains, manufacturers, customers, waste collectors, and myriad others. That’s not to disparage actions being taken. If anything, it’s a rallying call for all of us who care about this to realise that our power is solidarity.

As I stressed during a strategy session at RightsCon Online 2020 that brainstormed how we can create a roadmap for policy action as it relates to environmental sustainability and Internet governance, the fact is we cannot be everywhere all the time. There are so many issues involved stretching over so many agendas and expertise that we need to work on them together. We need to cross-pollinate between communities working on these issues, and build bridges between ourselves and the people, institutions, and companies that influence decision-making, including local and regional governments. Internet governance presents a framework that can realise this, and when complemented with more holistic and sustainable engineering and design, there is real potential to enact meaningful change. At the same time, we’re only now at a point where the wider Internet governance community is beginning to understand the importance of addressing sustainability. I am careful not to overembellish; this realisation is not universal, and there is still much work to be done and many minds to convince.

What you can do

The first step to take is to understand that you can make a difference. Solidarity is more important now than ever, and we need your skills, your voice, and perhaps even more importantly, your vote—in political elections, at your workplace, and in your communities. We cannot, and should not, see environmental sustainability, human rights, and climate change as separate. They are, in fact, inextricably linked at the very core, and one of the many threads that ties them together is the Internet. As I’ve highlighted before software designers, network operators, and technology companies have multiple tools at their disposal to enact change—from promoting circular economic methods with your purchasing (via rights-based procurement processes), network development, and software suite choices, to extending the lifetime of your equipment and fighting for the right to repair older but still high-quality devices. Perhaps even more important, though, is simply getting involved. Consider reaching out to new communities, such as the Green Web Foundation, ClimateAction.tech, and Association of Progressive Communications (APC), participating in fora, such as the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) or RightsCon, that may be unfamiliar at first but still worth your time and expertise. IGF 2020, for example, will feature an entire track dedicated to the environment (as well as one dedicated to inclusion), and anyone can participate in these sessions since it’s an open platform and will be held online in October and November.

Ultimately, though, all of us have a duty to champion for more sustainable technology, and now is the best time to work towards a sustainable recovery. A substantial component of that recovery means prioritising how we can continue to build an Internet that is more inclusive, not just of new and marginalised voices, but also one that truly places the planet and human rights before profit.

We have so much work to do, and collaboration will be our only saviour. Help us make it happen!

About the author

Michael J. Oghia is a Belgrade-based consultant, editor, and researcher working within the sustainability, Internet governance, and media development ecosystems. He is currently the advocacy and engagement manager for the Global Forum for Media Development (GFMD), an Internet Rights and Principles Coalition (IRPC) steering committee member, and a RightsCon Environmental Sustainability & Human Resilience track co-chair. Michael has more than a decade of professional experience working in conflict resolution, journalism & media, policy, and development across five countries: The USA, Lebanon, India, Turkey, and Serbia. Michael also loathes referring to himself in third person. Twitter: @mikeoghia