Welcome to the Museum of the Fossilized Internet. This miniature museum was founded in 2050 to commemorate two decades of a fossil-free internet and to invite museum visitors to experience what the coal and oil-powered internet of 2020 was like.

Gasp at the horrors of surveillance capitalism. Nod knowingly at the plague of spam. Be baffled at the size of AI training data and lament the binge culture of video streaming.

Built at an accessible scale by Gabi Ivens, this miniature museum is a research object to explore the major contributors to the internet’s pollution and spark conversation about the climate crisis.

Nine exhibition pieces invite visitors to consider the impact of online advertising, streaming, legacy code, AI training data, and more.

“To explore something so big, we first made it very small.”

Gabi Ivens, creative lead and miniature maker

Exhibition Objects

Generation Scroll, 2020

It is said that between 2005 and 2010 society left behind Generation Hyperlink and entered Generation Scroll. Generation Hyperlink began when Tim Berners-Lee created the first webpage in 1990, a page that contained four hyperlinks and weighed around 2 Kilobytes. Three decades later the average weight of a website was 1966 Kilobytes.

Scrolling through a website with a mouse or trackpad allowed developers to add massive chunks of content into a single site, which translated into a “richer” user experience but also dramatically increased the amount of energy and resources needed to load the page.

For those living in Europe in 2019, the average user would scroll the equivalent of 180 meters each day, half the height of Berlin’s TV Tower.

Since the 2024 collapse of the online ad industry, websites have now entered into “Generation Just Enough”, prioritizing only necessary content delivered in the most sustainable way, respecting user’s choices and limiting the number of daily adverts served.

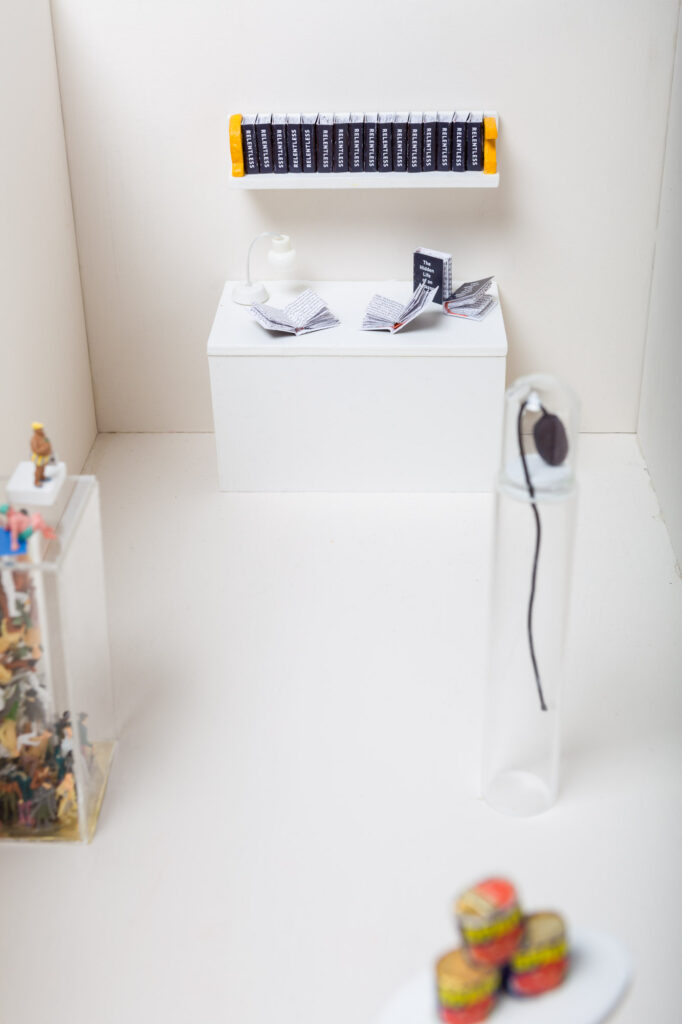

Relentless, 2020

In 2020 the world’s largest online retailer was a company called Amazon, a titan of streaming and cloud computing. Amazon, however, was not this company’s first choice of name. It was in fact, Relentless, a URL still owned by the company’s founder and CEO Jeff Bezos.

In 2019, the artist and researcher Joana Moll bought Bezos’ autobiography The Life, Lessons & Rules for Success: The Journey, The Teachable Moments & 10 Rules for Success Cultivated from the Life & Wisdom of Jeff Bezos on Amazon. To carry out this online order, she was taken through 12 different interfaces and had to load 1,307 scripts and documents, resulting in 87.33 MB of information and approximately 30wh of energy. On display are 20 volumes representing 8,724 A4 pages worth of code required to order that one book through Amazon’s website. This code reflects the accumulation of legacy code through developers adding more code at different moments of time, and the online surveillance tracking and ad economy that dominated the energy intensive online experience of 2010-2030’s.

Spam, Spam, Spam! 2020

“Spam, Spam, Spam!” The 20th century comedy group Monty Python sang louder and louder to drown out the sound of a customer ordering a spam sandwich. And just like this retro sketch, spam emails got their name from their ability to drown out real conversation with inane chatter.

Back in 2019, an approximate 158 billion spam emails were sent, accounting for 55% of all email traffic, with an average footprint equivalent to 0.3g of carbon dioxide emissions per message. Email wasn’t the only medium plagued by spam. The spam economy was expansive and included fake social media accounts, fake Facebook likes, fake retweets and fake Instagram followers.

To get an idea of the size of this problem, back in 2019 the relic social media platform Facebook removed 2.2 billion fake accounts in the first quarter of this year. Each active profile is estimated to account for 281 grams of CO2, the same carbon footprint as a medium latte. Multiplied by 2.2 billion, these fake accounts add up to a lot of medium lattes!

Forever Life, 2020

In 2020 Second Life has 4,000 server computers in order to run their virtual world that houses a population of 12,500 avatars active at any one time. For each of these computer users operating these avatars per year they would roughly translate to driving an SUV around 2,300 miles or 3,700km. But what about those avatars that get created and are never to be used again? These avatars are still wandering around the Second Life servers. It isn’t just avatars wandering restlessly but cat videos saved years ago on a cloud service and forgotten, or a video saved on a hard drive never to be seen again — all of these continuing to drive up emissions.

In 2020 every internet user generated an average of 1.7 megabytes of data per second. Moreover, a report published in 2019 by the consulting firm Splunk stated that 55% of the data generated by major IT companies was useless, but kept nevertheless, often it was technically impossible to erase a user from the Internet, as part of its data was kept in unknown locations.

Keeping up with all this data inevitably raised the need to expand the architectures that allowed this data to exist: namely data centers. An individual hyperscale data center typically had a footprint of more than 10,000m2, but some of them could be even bigger. The data center industry consumed around 2% of electricity worldwide. Data centers not just consumed enormous amounts of electricity, but also occupied extensive surfaces of land and required vast quantities of water to operate.

Socks and streaming, 2020

In 2020 online video, gaming and multimedia represented 82% of all global IP traffic. Netflix was the biggest company offering video on demand services.

These companies opted to serve their content continuously and uninterrupted, often by utilising autoplay functionality, so much so that Netflix bought out their own line of socks that detected when the viewer had fallen asleep and automatically paused the show they were watching. Video on demand services like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Hulu generated the same volume of greenhouse gas emissions as the country of Chile.

To give some perspective, the hit music video for the now classic song “Despacito” had five billion views on YouTube. To generate this kind of energy it would either take 850,000 barrels of oil or 93 wind turbines running for an entire year.

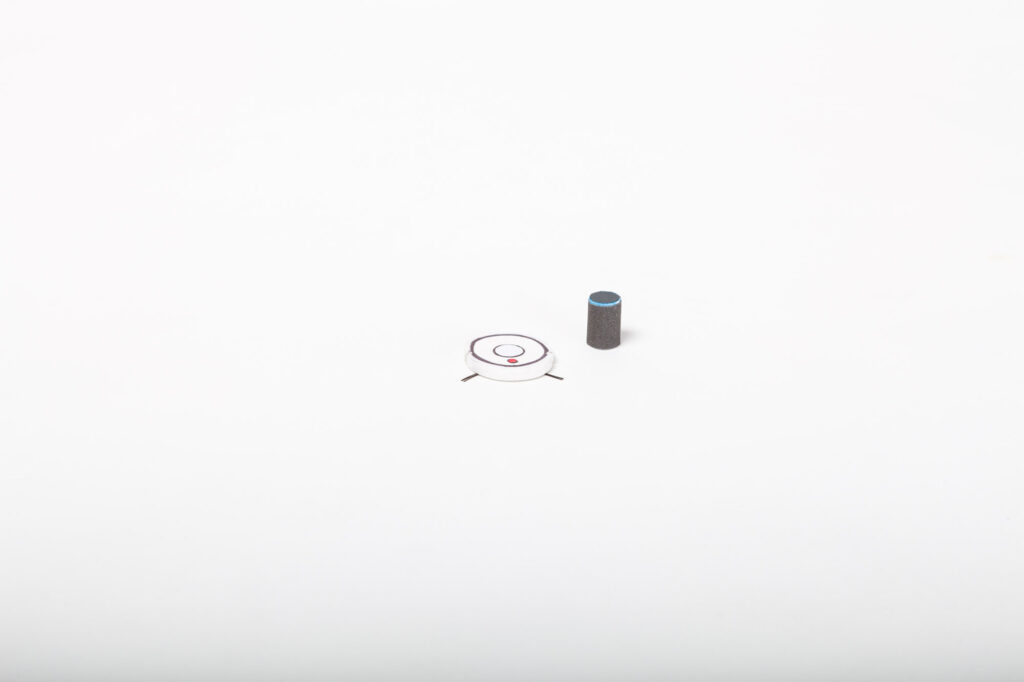

Barry and Alexa, 2020

Data ethnographers asked an Alexa device back in 2019, “How many kilowatts per hour does an Echo Dot use?”, Alexa replied “Sorry I do not know that”. In 2020, there were more than 30 billion devices connected to the Internet, almost four times the global population. These were not just Alexa’s but also smart meters, mobile devices, lights, cameras, and robot hoovers. The amount of data produced and collected by this ecosystem of interconnected objects and the architectures necessary for them to exist expanded daily.

Big data and AI: Training AI

This framed picture of Paglen’s work features selections from the ImageNet dataset for object recognition. AI needed vast amounts of data in order to understand our world. In 2020 China had a massive system of data collection, which allowed the country to build and own the largest datasets used to train AI in the world. GTCOM, one of the leading AI companies at the time, was claimed to have harvested between 2 to 3 petabytes of data annually. Back in 2025, AI workload accounted for a tenth of the world’s electricity usage. Training AI was generally quite energy intensive, for example, training several popular and large AI models produced the same CO2 as 34 passengers flying between Sydney and London. In the wake of the Econet Agreement, the field of Tiny AI emerged, where computer scientists competed to use the smallest training datasets possible along with the reemergence of principles contained with analog computing from 1960s.

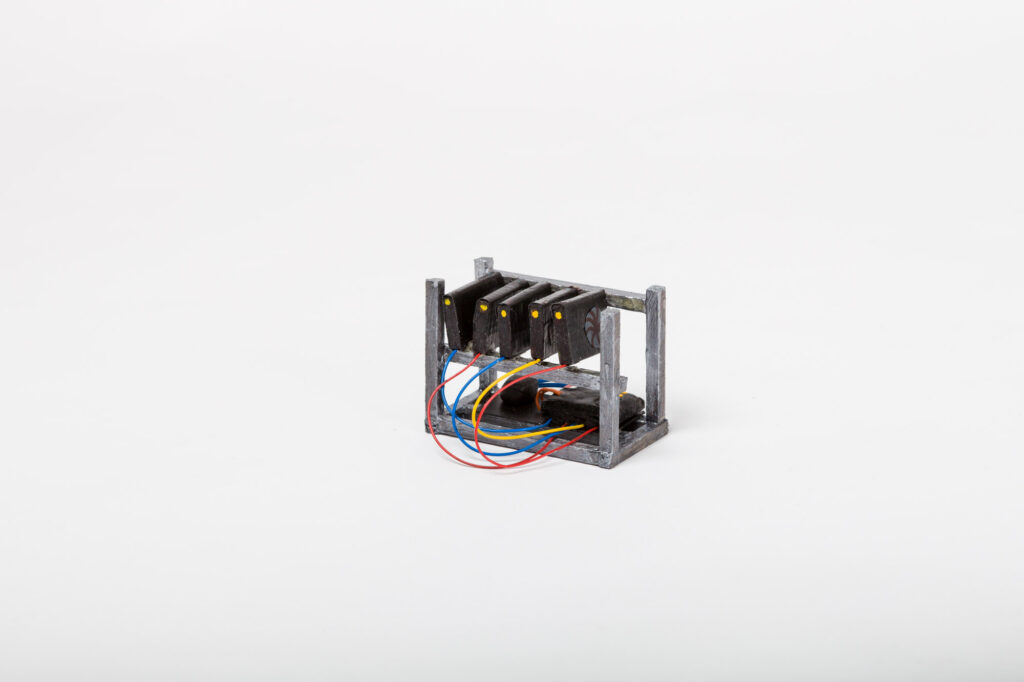

Mining Rig, 2020

Even though Blockchain had many potential uses that extended far beyond digital money, Blockchain became famous in the late 2010s as the underlying system behind Bitcoin and other digital cryptocurrencies. Research showed that the electricity required for Bitcoin alone generated as much CO2 as cities like Hamburg or Las Vegas back in 2019. After this research was announced, cryptocurrency mining was regulated in places where power generation was particularly carbon-intensive.

Big Banner Ads, 2020

The average internet user of 2020 was served 1,700 banner adverts per month. At the time there were estimated to be 4.48 billion people active on the internet which means that 4.48 billion people were receiving 7.4 trillion banner ads each month. A study conducted in 2016 evaluated that the carbon footprint of online advertising in total constituted 10% of the total emissions of the internet. That was a lot of energy for something that has a success rate of one purchase per million ad impressions.

About the Author

Gabi Ivens created the museum with support from Joana Moll and Michelle Thorne. Thanks to Nina Zimmermann for the photography and to Cathleen Berger for making this project possible. This work was commissioned by Mozilla’s Sustainability Program.