(This article is a reduced version summarizing they insights of the publication: Varon, Joana; Egaña Rojas, Lucía: Compost engineers and sus saberes lentos: a manifest for regenerative technologies. Coding Rights, Rio de Janeiro, 2024. Available at: codingrights.org/docs/compost_engineers. It was originally produced as a contribution to the Feminist AI Research Network (FAIR), with support from the Latin American Hub of that network.)

The concept “artificial intelligence” is a loaded term, sparking a very particular imaginary of possible futures: Silicon Valley and Hollywood’s fast and metallic futures, incompatible with values, desires, and dreams of decolonial, antiracist, and transfeminist visions of being on this planet. What imaginaries does this terminology evoke? What are the limitations of applying the term AI to feminist technological practices? What are the alternative epistemologies and practices that could help us develop decolonial feminist regenerative tech?

This article summarizes a broader manifesto/research piece developed by the authors in the context of the Feminist AI Research Network, to propose an epistemological, historical, political, and creative exercise to envision technological development guided by social-environmental justice and feminist principles, resulting in technologies of life and del buen vivir.

To achieve this goal, we have journeyed through the history of Western science fiction to untangle the colonial and patriarchal imaginaries that still guide mainstream technological development.(1) Given this diagnosis, we propose an exercise to decolonize our tech imaginaries by drawing from feminist theories, biology, and ecology studies, particularly mycology, soil studies, and symbiotic approaches to evolution. Employing radical imagination and speculative narratives, we propose a figuration: the compost engineers, to inspire technological development that can be regenerative and exist in symbiosis with Earth, all its beings, temporalities, and rhythms. We seek technologies of life, standing in opposition to current technologies of war, extraction, and domination.

Compost Engineers: An Alternative Figuration

Many intelligences that emerge from deeper senses are being erased when the logic of problem-oriented mathematical thinking is mainstreamed as intelligence. Many kinds of intelligence are not included in the biased concept of “Artificial Intelligence”. This model of intelligence makes invisible a series of proposals, materialities, and methodologies that do not respond to its value system. The Western episteme constructs reality through hierarchical binarisms presented as universal, perpetuating colonial logic and ideas of purity that exclude mixture or “contamination”. Many Latin American feminists have contributed to exploring the nuances and intersections of things and beings which are neither pure nor clean (Gloria Anzaldúa (2), Ochy Curiel (3), Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (4)). Inspired by them, our proposal here is to explore the compost engineers as an alternative figuration to reposition other kinds of intelligences at the center of our technological development. We are also inspired by the speculative narrative The Camille stories: children of compost, by Donna Haraway. The story tells us about “communities of compost” and how their “practices grew from the sense that healing and ongoingness in ruined places require making kin in innovative ways.” (5)

The compost originated from waste to create life. The work of the compost engineers is to take to the garbage all these western-centered patriarchal imaginaries and practices that are leading AI development and let it compost. We will nourish it by feminist values and views as a constitutive outside to grow a space for technologies that – instead of generating more and more content, trash, extraction, and oppression – focus on regenerating what we once had.

The Constitutive Exterior of AI: Composing Western and human-centered notions of intelligence

Why does the prevailing notion of intelligence correspond exclusively to the human (and its possible replicas)? Can we reposition as intelligent the ingeniousness focused on regenerating instead of controlling humans and the other beings?

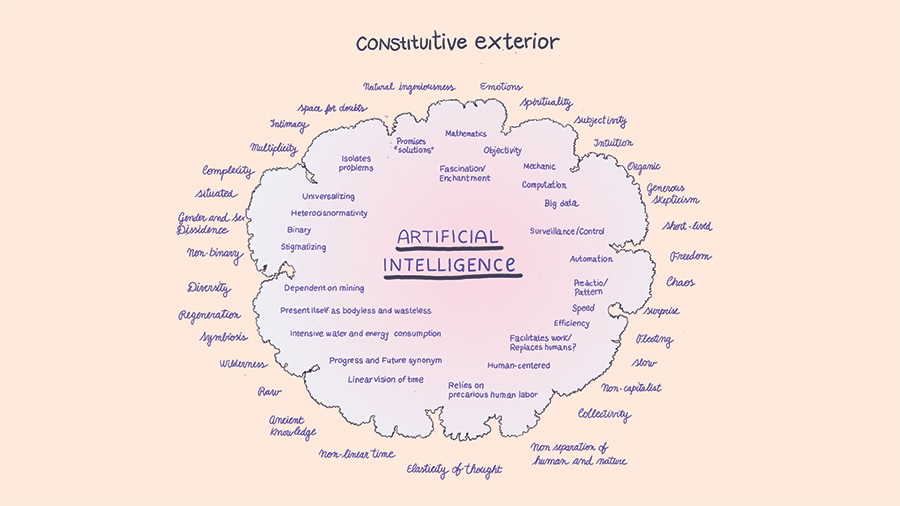

To determine which values, ethics, ways of doing, and policies remain outside the notions contemplated by the contemporary idea of AI, we have been developing this chart. It helps us visualize answers to the question: What is left out when we use the term Artificial Intelligence?

We can see that a lot of values, principles, and world views that are important to feminists and decolonial theories are left outside the mainstream notion of AI. On the inside, ideas that constitute AI: the universalisation of a cisheteronormative white patriarchal vision, objective rationality, human-centered world view, as if we were detached from the environment, a notion of progress guided by the machinic vision of the future, fastness, speed, efficiency, competitiveness… values that drain the planet. Left out are values that are important for a decolonial, feminist, anti-racist, ecological perspective, such as complexity, subjectivity, spirituality, diversity, regeneration, inter-relationality, and co-operation. Can we think about technologies from the outside?

Can we reverse the logics and imaginaries that have permeated conceptions of technology for centuries up to today?

Can we contribute, as humans, to the collective processes in which living and non-living entities participate in non-destructive ways? Technologies that are situated, instead of universalizing, that are non-human centric and, as such, are connected with other rhythms? Slower than the sickening pace of capitalism requires?

The answer to this question has the potential to reverse all the power dynamics established among humans since colonization and the industrial revolution that we are bringing into technological design. It repositions intelligences and practices historically depreciated by the dominant Western patriarchal capitalist worldview, revealing re-emerging epistemologies in this ecosocial crisis. It gives back the power to those who, despite centuries of oppression, have preserved ancestral and traditional knowledge.

Intelligence as a multispecies contamination

Intelligence, although difficult to define, is relational and is activated and mobilized in the face of stimuli and interactions. Urban Western life increasingly reduces our senses while overstimulating rapid visualities and hormone production to keep us as cogs in a controlled, clean, predictable lab-like environment. If intelligence is a relational element, and therefore a dynamic one, why not consider that intelligence expands as we interact with other beings, living and nonliving, in their most varied and multiple forms? Why not consider as highly intelligent all those systems that coexist in multiplicity and unpredictability, sometimes with elements that are even imperceptible to our eyes?

It is equally important not to “humanize” the other species or entities, not to expect translations into our language or our models of learning, knowledge and/or intelligence. Even so, from our human, low, and partial understanding of the world, many species have demonstrated high degrees of intelligence. Examples include spiders’ webs, earthquake-predicting animals, mycorrhiza, and trees demonstrating forest intelligence, which is symbiotic and regenerative, unlike the human-centered Western Cartesian proposition.

Intelligence is condensed in the collaboration between different species. It is in these interactions with the improbable, the unknown, and the different that unsuspected intelligences appear.

Perhaps this is precisely the exercise we must embrace—especially those of us who are urban, digitally dependent, and participating in a culture whose hegemonic technologies have systematically erased ancestral ways of knowing. Reconnect with other environments, beings, entities, processes, and systems that can make us part of a circuit of multiple intelligences, beyond humans. After all, we must take responsibility for our lifestyle’s consequences, seeking territorial, technological, and spiritual reparation.

Saberes lentos

In this sense, the proposal is that we become and listen to the “compost engineers”. We consider compost, the interactions between living and non-living beings as part of a choreography of the ecosystem. All this is taking place in plural, diverse ways, and “intelligent” (or wise), though absent from current AI. As ecofeminist Vandana Shiva argues, soil can be a place of repair. An example is the fact that metal contamination can be remediated mycologically, as copper, zinc, iron, and other heavy metal waste can be attracted by biosorbents developed from mushroom mycelium or mushroom compost.

In the book The Mushroom at the End of the World, anthropologist Anna Tsing studies the matsutake mushroom, which grows in the ruins of capitalism. Tsing invites us to other ways of seeing, beyond the anthropocentric perspective. A call for observations capable of noticing the “multiple temporalities and unstable assemblages between humans and non-humans.” (6)

Our compost engineers move between the living and the dead, between the “healthy” and the rotten, between the various intelligences in the soil.

As indicated by Chilean biotechnologist Daniela Torres, director of the Chile office of the Fungi Foundation, whom we interviewed for the manifesto, there is intelligence in soil and microorganisms that inhabit it. We should focus on the smaller processes, but depart from a non-romantic view of symbiosis, as Daniela also highlighted, competition and collaboration happen simultaneously in nature—different life strategies overlap in ways that challenge anthropocentric views.

We want to reclaim these wise and complex processes, technologies of life, that the figuration of the compost engineers offers us to inspire slow systems preserving life and reducing damage. Healing, restoration, and repair are what researcher Bárbara Santos considers as different kinds of technologies in her book “Curación como tecnología”, which features interviews with “sabedores da Amazonia“. “In the city people go very fast, technology overthere is part of people’s lives, Western technology dominates people and does not allow everyone to know their own life, the relationship with other people and nature”(7), said Jesús León Muipu from tatuyo people, inviting us to align with slow knowledge temporalities that we propose to cultivate with compost engineers.

Prototype Proposal: Compost Engineers’ Regenerative Systems

The Compost Engineers’ Regenerative Systems is a figuration, but also a technology that enables the creation of models and tools with pedagogical, restorative, and regenerative purposes. It departs from the observation of intelligences that compose a wild rustic garden, as it serves to understand relations that have been forgotten in the development of conventional digital technologies. In that garden, we are the engineers, just as the soil, fungi and mycelium, bacteria, microorganisms, insects, plants, and other beings that will be interacting in that piece of land, in symbiosis.

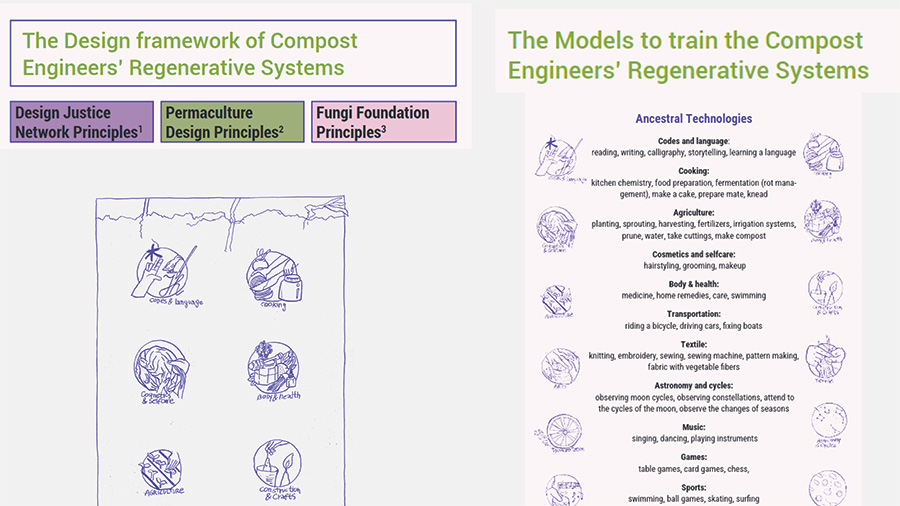

The Compost Engineers and their slow knowledge seek to imagine technologies that operate and perpetuate notions of responsible consumption, beyond the circular economy and minimum waste, while recalling ancient knowledge and technologies. As a first step, we propose a rustic wild garden as the space of action to develop the compost engineers’ regenerative systems with the following framework, infrastructure, and training models: Design Framework: We merge Design Justice Principles, Permaculture Principles, and Fungi Foundation Principles to create a substantial framework for the Compost Engineers to build and observe their regenerative systems.

Infrastructure:

The wild rustic garden serves as the main infrastructure and platform, including compost of organic waste, fungi kingdom, water storage systems, irrigation and water reuse, diverse plant species, vegetable gardens, solar energy, and low-fi labs with microscopes, sensors, cameras, and microcontrollers.

Models to train the Compost Engineers Regenerative systems:

It is not by chance that a series of ancestral techniques and technologies have been dismissed as useless, unsophisticated, or primitive. Our prototype proposal aims to reclaim not only the sophistication of these technologies, but also highlights the fact that these are technologies that, from the start, are friendly to the environment and other ways of living. These ancestral technologies do not have to be sought in an archaeology museum, as they are still present in our lives and we often know them, thanks to the knowledge that is transmitted many times in a non-institutional way, in domestic or community environments. They are also low environmental impact technologies that often have restorative effects.

Therefore, the model for the Compost Engineers’ Regenerative Systems will depart from some of these ancient technologies that will be implemented concerning the rustic garden, recovered as central to the development of technologies of life, technologies that work towards the collective. They will serve as the model to train the regenerative systems we want to develop.

Instead of artificial, we propose natural, organic, multiple, chaotic; instead of a rational data-led intelligence, we propose a reconnection with the uncontrolled saberes de la tierra (earth and soil wisdom) and with all the senses. We propose a reconnection with technologies of life, technologies del buen vivir. It is an ecosystem that is simple and complex at the same time, that functions in an absolutely intelligent way, but whose intelligence is neither artificial nor patriarchal nor human-centric. Ultimately, the Compost Engineers want to open space to imagine…

Footnotes

- If the reader wants to learn more about histories of Western science fiction that have shaped mainstream understanding of technology, we suggest you to read the complete manifesto.

- Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera. The New Mestiza, San Francisco: aunt lute books, 1987.

- Ochy Curiel, “Crítica pós-colonial a partir das práticas políticas do feminismo antirracista,” trad. por Lídia Maria de Abreu Generoso, RTH. Revista de Teoria da História. Universidade Federal de Goiás 22, no. 2 (2019): 231-245.

- Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Ch’ixinakax utxiwa. Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores, Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2010.

- Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016: 138.

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. O Cogumelo no Fim do Mundo: Sobre a Possibilidade de Vidas nas Ruínas do Capitalismo. São Paulo: n-1 edições, 2019: 63

- Original quote: “En la ciudad la gente va muy rápido, la tecnología de allá es parte de la vida de la gente, la tecnología occidental domina a las personas y no permite que cada uno conozca su propia vida, la relación con otras personas y la naturaleza”. Ibid: 34.

Joana Varon is Founder, Co-Executive Directress, and Creative Chaos Catalyst at Coding Rights, a feminist organization that contributes to the debates about the development, implementation, and regulation of technologies from a collective, transfeminist, decolonial, and antiracist perspective of human rights. Former Technology and Human Rights Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy from Harvard Kennedy School, with Master’s in Law and Development, she is currently a PhD candidate in Design and Anthropology at the School of Industrial Design from Rio de Janeiro State University (Esdi-UERJ), researching how to decolonize tech imaginaries. Alumni of the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University and Former Mozilla Media Fellow, she is co-creator of several creative projects operating in the interplay between rights, arts, and technologies, such as: Una Bolsa de Semillas: ciencia ficción en Abya Yala, transfeministech.org, museamami.org, chupadados.com, #safersisters, Net of Rights, protestos.org, freenetfilm.org, among others.

Lucía Egaña Rojas holds a Ph.D. in Audiovisual Communication and has also studied Art, Aesthetics, and Creative Documentary. As an artist, she works on projects that problematize the construction of social imaginaries and the sources of hegemonic knowledge. Her interests span feminism, methodologies, technology, North-South power relations, colonial and migratory processes, and extractivism. Her projects materialize in artistic production, writing, research, and pedagogy. She has been a teacher and member of the academic direction of the Independent Studies Program (PEI) of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona (MACBA); a member of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Universidad de Barcelona; guest professor in the M.A. in Gender Studies at the Universidad de Chile and at in the MUECA M.A. (UMH); and also participates in the FIC research group (Fractalities and Critical Research) at the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona.