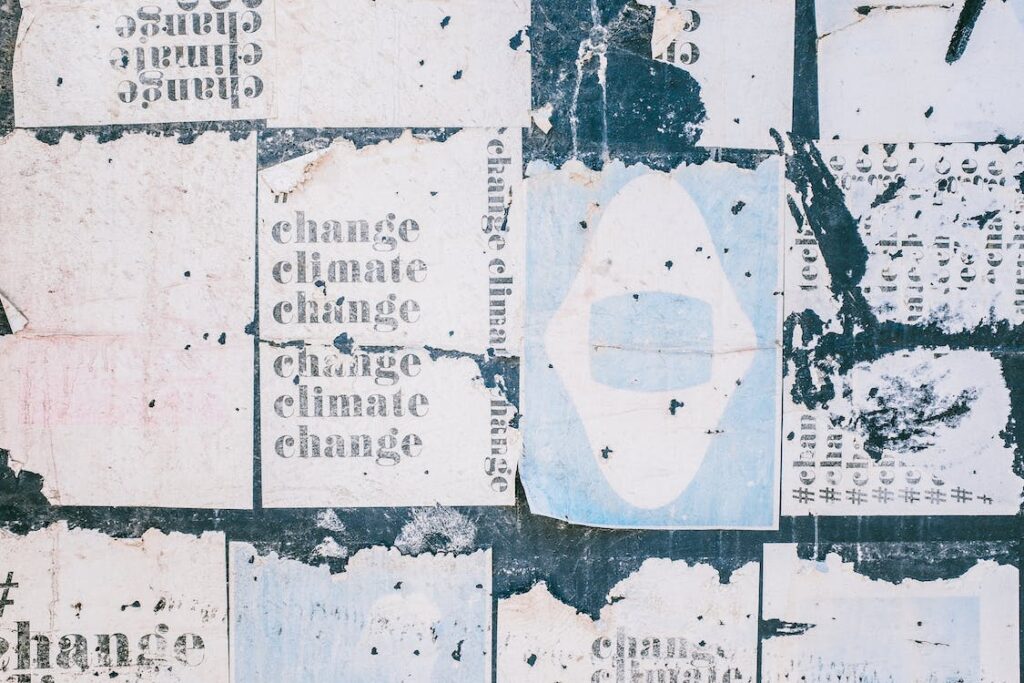

Open climate is the meeting of the movements for climate justice and the knowledge commons.

The co-editors of this issue of Branch Magazine met on a caravan. Inspired by the routes and exchanges of the old trading caravans, we have been traveling at our own time and pace, sometimes alongside each other, sometimes meeting again to rest and reorient. We’ve thought of these moments as our caravanserai.

These spaces have been essential for our own personal and professional journeys—to take time to pause and reflect critically, explore nascent ideas and well-thought out ones, to immerse deeply into new contexts and to meet fellow travelers.

The caravan

During the pandemic, our caravan moved online. Throughout lockdowns, personal loss, isolated winters and hot summers, we gathered around the glow of our Zoom room and warmed our souls with stories from the road and our hopes and fears of the journey ahead.

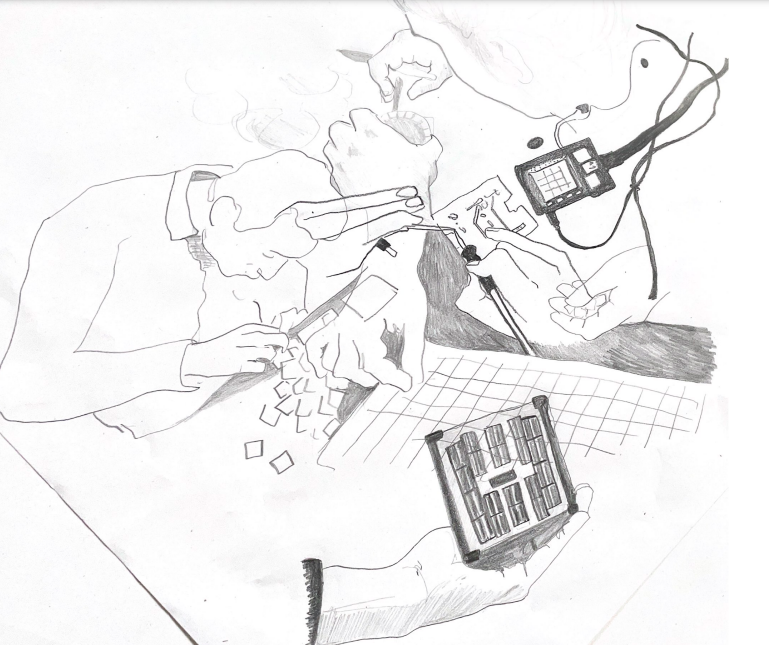

Babitha George, director of the design research studio Quicksand, dialed in from Bangalore and told stories of craft technology and community-centered design. She created Decentralizing Digital, a beautiful design research project done in collaboration with community partners, small-scale farmers in India and local artists.

Shannon Dosemagen, director of the Open Environmental Data Project, called in from New Orleans and shared her interest in socially situated data. Building on these ideas, she co-authored the article Open Climate Now inviting the open movement to take climate action.

Michelle Thorne, senior adviser to the Green Web Foundation and editor of Branch, was often facemuted on the calls from her home in Berlin, sometimes pushing a stroller or watching her kid play on a snowy, deserted playground. She was interested in how to build and maintain the knowledge commons in a way that isn’t extractive nor harmful in its emissions and environmental degradation.

From our conversations, we knew we wanted to hear from others who were also dreaming about sustainable and just futures. We wanted to know: how is sustainable technology tied to community governance, to the knowledge commons and digital sovereignty? What does an internet look like that takes a craft approach—honoring local knowledge, local materials, and sustainable practices. And along this caravan, where are the places that foster an ongoing dialogue about climate justice and the open movement?

From our rest stop conversations, we realized there is much to unlearn, to reimagine, to regenerate, to build and debate together. So we decided to publish a special issue of Branch magazine to celebrate these topics.

Open Climate

The fourth issue of Branch Magazine is dedicated to the theme Open Climate.

While we are faced with urgent crises, we wanted to acknowledge that solutions may be slow. We wanted to divest from the narratives of disruption and solutionism and make space for embracing slowness and hope. We sought a future that is anchored in a respect for different kinds of knowledge. The stakes are high, and we need stories and narratives that bring us together and include us all. This is the power of openness.

As we opened a call for proposals for this issue, we invited fellow dreamers and doers to respond to a social imagination that inspires climate action and to share what actions they are taking towards a more just and sustainable internet.

We wanted to turn away from the daily inundation of hot takes that often privilege doom and despair. We wanted to prioritize initiatives that are community-centered, place-based and contribute to the commons, as we felt strongly that this was imperative for a more just future. We wanted to consider together how we could harness the tools of the open movement and apply them to climate justice and more rapid climate action, while also stewarding the knowledge commons and accounting for its environmental impact.

Proposals arrived in a broad array of formats—video, audio, writing, visual art, physical objects and code—even sensory experiences of climate change. We hosted an online ideas jam with all the contributors and invited them to make a new work for this issue or, in the spirit of free culture, to remix and repurpose existing pieces. We are very grateful to all the contributors for their kindness and passion in this process.

In this issue you will find explorations of hi-craft rather than hi-tech. You will read about the hope of seed libraries and repair shops. You will learn about the leading open projects on measuring the internet’s carbon emissions and mitigating environmental damage from manufacturing hardware. You will be invited to walk along the rivers of India and to consider a handmade computer. You will be delighted in the alternative computing environments that have always been here: in rural places, among sovereign communities and with people prioritizing sustainability over reckless speed.

Open Climate is a living, breathing practice. You will find some of its shapes and practitioners here. We hope it sparks connections for your work and that we might join each other on a caravan towards more just and sustainable futures.