Working with rural communities in Karnataka, India, Decentralising Digital is an ongoing research project seeking to co-create new narratives for decentralised digital futures.

We are exploring how developments in emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things, the voice enabled Internet, machine learning and artificial intelligence might be harnessed to meaningfully support rural communities in India. We imagine that the work presented here can be adapted and used by other communities and stakeholders, in their own work in reimagining different, more sustainable futures for these communities.

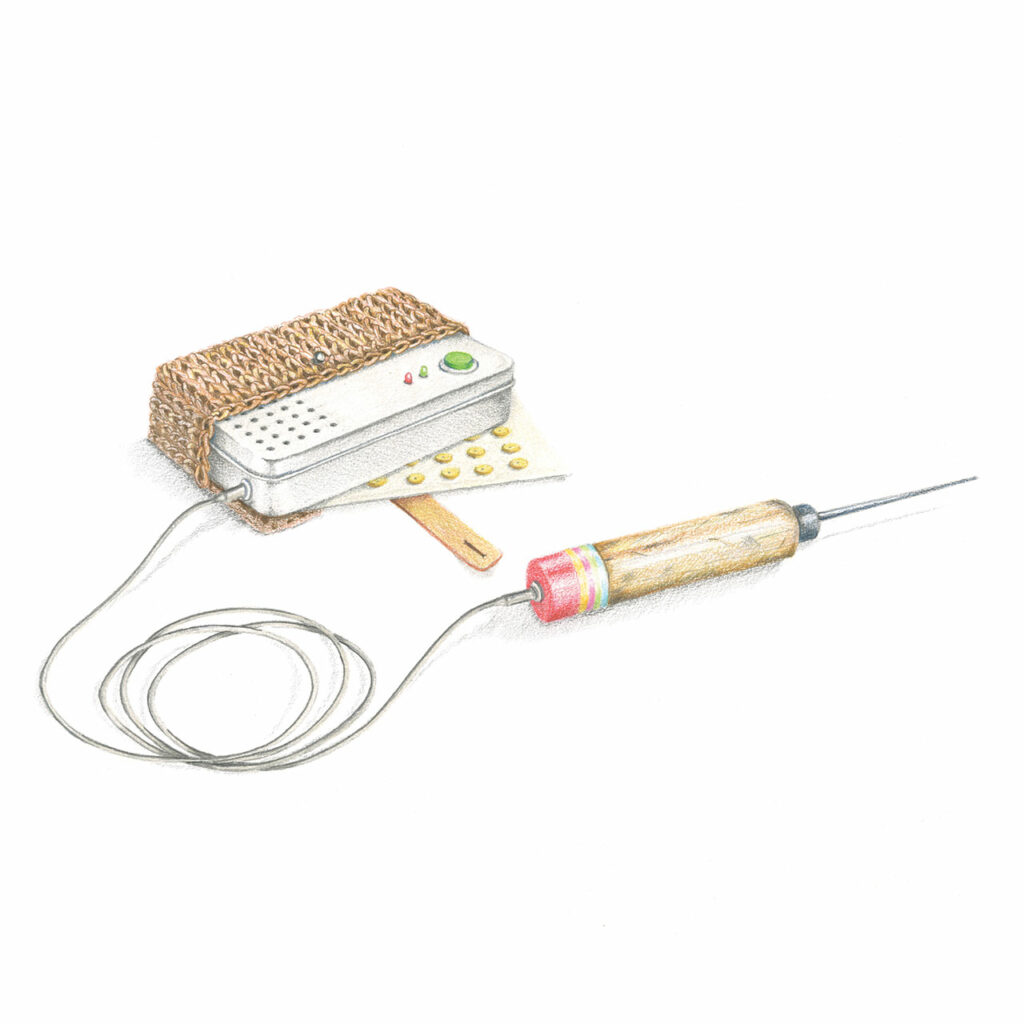

We imagined a series of artefacts that might be found in these diverse futures. These artefacts intentionally adopt a visual and material language rooted in the knowledge of the people and the communities we worked with.

Continue reading “Decentralising Digital: Artefacts from Hopeful Futures”