In this collection of profiles, gardener and farmer activists provide a glimpse of how they are working towards mitigation and changing the soft adaptation limits of the conventional food system in the Anthropocene, garden by garden and seed by seed.

Introduction by Daniela Soleri

We’re in the thick of the Anthropocene—the name discussed by scientists to describe a geological epoch in which human activities including agriculture and manifestations of capitalism including colonialism, intercontinental slavery, and industrialism have altered planetary systems. The trends characterizing this epoch are no longer abstractions confined to scientists’ graphs—increasing atmospheric warming, environmental destruction, species extinction and deepening social inequity are well underway. Many people, especially those with less privilege, are experiencing in very real ways the negative consequences of the trends’ accelerating impacts.

We need to figure out how to slow and hopefully reverse these trends. But even if we can dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, environmental destruction, and inequity today, Anthropocene trends well underway. That means that the reality of life on Earth in the 21st century requires massive adaptation if we hope to sustain the conditions for human well-being and planetary health.

Adaptation is crucial in the Anthropocene, but there are limits to the changes that human society and the planet can adapt to successfully. Exceeding those limits will have catastrophic outcomes. Adaptation is a central focus of the Working Group II contribution to the recent IPCC 6th Assessment Report. It helpfully distinguishes between “hard” and “soft” adaptation limits. Chapter 16 of that report has lots of examples of both hard and soft limits we face globally. Hard limits reflect the biophysical reality of Earth—they are hard because they cannot be changed and once exceeded their consequences cannot be avoided. It’s simply not possible to successfully adapt to them.

These limits are tipping points. Once passed, they lead to a negative change in the system that is impossible to reverse. For example, a change in the climate results in new stable weather patterns that make growing food, or even living, no longer possible in some areas. The breakup of large glaciers leading to sea level rise is another tipping point that would flood the homes and fields of many millions of people. Ignoring and not mitigating Anthropocene trends moves us closer to hard adaptation limits which cannot be changed, and beyond which human life will be extremely difficult.

Soft adaptation limits are constraints to adaptation that are usually human-made and can therefore be changed, permitting successful adaptation. Examples of soft limits include water policies and agencies in the US west that fail to encourage conservation and the inability to build more localized and healthy food systems due to the hyper-capitalist system. Soft adaptation limits remain in place when there is a lack of imagination about what could be possible, a lack of will to try alternatives, or because making short-term profits from the existing unsustainable system is favored over alternatives that support justice and human and planetary health. But we can move or remove some soft limits by changing policies, institutions, and processes to better reflect our goals and values.

The open movement helps shift soft adaptation limits by reimagining and reconfiguring the processes, rights and relations around information and tools so that those can be more accessible and useful to society.

The open movement helps shift soft adaptation limits by reimagining and reconfiguring the processes, rights and relations around information and tools so that those can be more accessible and useful to society.

In food system activism, some community seed groups are reimagining and investigating alternative ways to develop, maintain and share agricultural seeds. Their overarching goal is supporting farmers and gardeners in changing the soft adaptation limits of business as usual, based on prosocial values about society and the planet. These explorations take different forms.

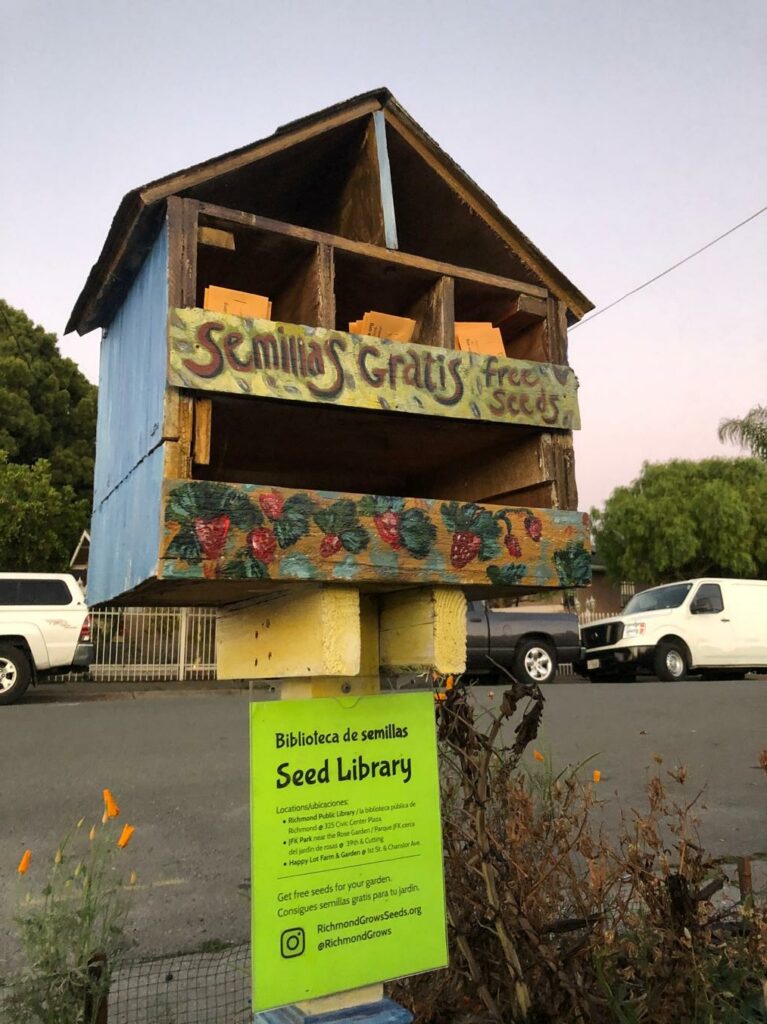

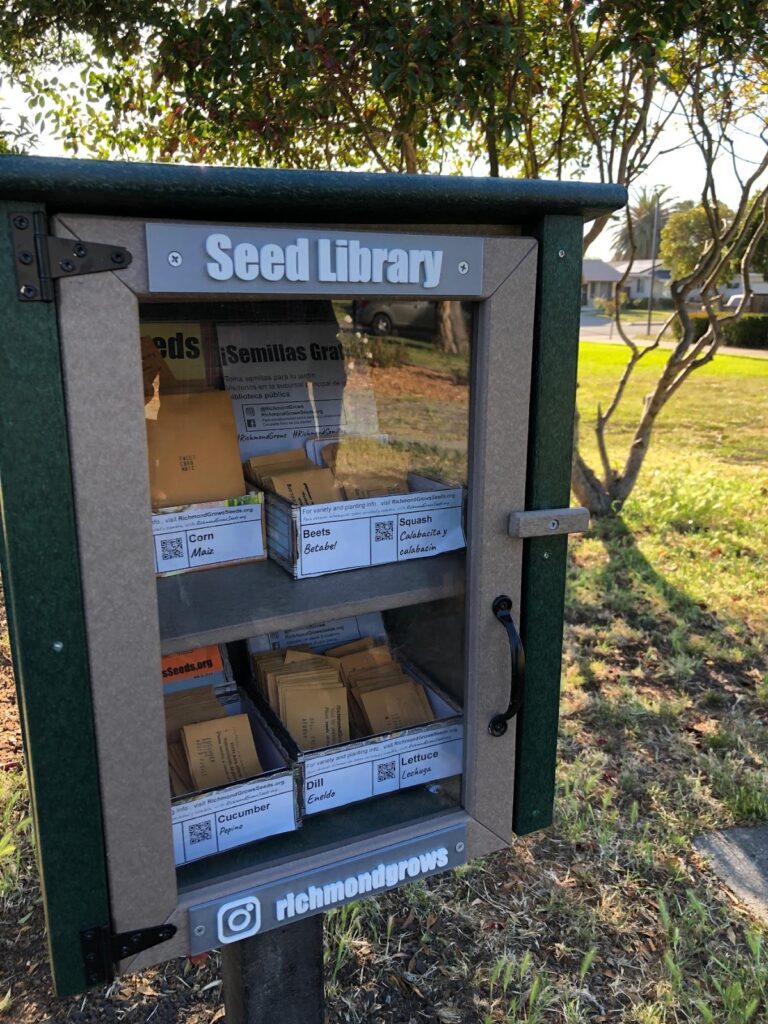

The Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library (RGSLL) is an example of a community seed group with the goal of accessible, appropriate, community managed garden seed stock, a reimagining of both material (locally grown, culturally appropriate seeds), and process (local crop variety caretaking, seed saving and free distribution) as commons, and physically located in probably the most widely recognized commons spaces in US society, the public library. In doing this work RGSLL pushes back some of the soft adaptation limits that make low resource urban gardeners vulnerable to Anthropocene trends.

The Experimental Farm Network (EFN) gives special emphasis to reimagining the organization of biological processes around varietal creation or conservation, including in some cases collaborative plant breeding, local adaptedness, and perennial agriculture. EFN is building the infrastructure to make collaboration among gardeners, farmers and researchers possible and meaningful, eroding the soft adaptation limits constructed by the isolation of diverse epistemologies and lived experiences.

Building on the work of seed libraries like RGSLL and innovative plant breeding like EFN, the Cooperative Gardens Commission (CGC) created a gardening and garden seed pandemic response leveraging mutual aid approaches to crises that reimagine not only immediate material aid, but also a restructuring of processes to prioritize core values such as justice and climate disaster mitigation. The CGC work tests prosocial approaches to shifting soft limits to Anthropocene crisis response, and creates the opportunity to learn alternative approaches for non-crisis situations as well. (A recent paper has more discussion of the biological and social investigations and responses to COVID-19 by RGSLL and EFN/CGC.) For these and some other community seed groups, their goals and values reflect both the urgency of the climate crisis, as well as their commitment to open, accessible institutions and processes that work intentionally against inequity and injustice.

The Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library

By Rebecca Newburn

The Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library (RGSLL) is open to all members of the community. Before the pandemic, we offered 100% locally grown seeds. During the pandemic, we purchased seeds from seed houses that aligned with our values because RGSLL seed was locked in the public library and unavailable to share. During the pandemic, we set up and provisioned 13 Little Free Seed Libraries around the city of Richmond, California, USA, that offered small free packets of garden seed to interested neighbors. Today, our seeds are once again available through the public library, and we are now transitioning back to locally grown seeds through our grow-out program. That program has community members commit to growing seeds out for the community and is primarily focused on breeding landrace varieties as well as preserving several heirloom varieties that are important to our community.

Open Plant Breeding: Crowdsourcing the Crops We Need to Survive Climate Chaos

By Nate Kleinman

I co-founded The Experimental Farm Network Cooperative (EFN) back in 2013 with the primary purpose of driving innovation in sustainable agriculture through facilitating collaboration among plant breeders, farmers, and gardeners, especially toward the development of new carbon-sequestering perennial staple crops.

With the exception of a few woody crops (mostly fruits and nuts), the temperate regions of the world utilize very few perennial food crops (like asparagus, rhubarb, and horseradish), while the vast majority of farm acres are planted in annual crops (especially hybrid wheat and genetically modified corn, soy, canola, and cotton). Industrial-scale farming of annual crops results in immense amounts of carbon pollution every year, including from chemical fertilizer inputs, fossil fuels burned by tractors, and the act of tillage itself, which leads to direct carbon emissions, disrupts soil life, and diminishes the soil’s ability to sequester carbon. Industrial farming also increases erosion, damages wildlife habitats, and exposes all life — including humans — to toxic chemicals on a daily basis. Its only advantages are seen by wealthy landowners and large multinational corporations. Perennial crops, on the other hand, reduce erosion, improve wildlife habitat, and require only organic inputs, all while sequestering carbon and producing healthy produce.

EFN and many others are working toward an agricultural system aimed not at corporate profits, but at the long-term sustenance of humanity. Farming based on agroecology — at once a practice, academic discipline, and social movement — is the only sustainable way to produce the food and fibre human society needs. Agroecology means farming in harmony with nature, largely through mimicking its processes, and it is the main form of agriculture practised to this day by most indigenous peoples around the world. Agroecology means abandoning monoculture — growing a single crop across a vast landscape — in favor of diverse polyculture.

But in order to fully transition from annual-based industrial farming to perennial-based agroecological farming, we need new crops and growing systems. In order to develop these, we must not be tempted by the easy answers of the corporate biotechnologists (whose careers are based on promulgating the fiction of their own importance), but instead, we must look to the past: to the earliest farmers who began domesticating wild plants over 10,000 years ago. This means applying to edible wild perennial plants the same selective pressures our ancestors typically applied to edible wild annual plants. Breeding perennial plants takes much longer than breeding annuals (since it may take three or many more years for one generation of a perennial crop plant to demonstrate its utility), but the end results could mean the difference between climate catastrophe for humanity and mere climate chaos.

One example I’m in the early stages of experimenting with is a plant called Plantago maritima, also called Sea Plantain or Goose Tongue. I had known about this plant for years, and even tried growing it once, but I didn’t fully appreciate it until last summer when I encountered a diverse little population of wild Goose Tongue growing on a rocky beach in Searsport, Maine. It was August, and the plants were healthy, full-sized, and laden with seeds. As soon as I tasted some of the leaves — mild, salty, crunchy, fresh, and savory — I knew I needed to collect as many seeds as possible and begin working with this plant extensively. Less than a month later I collected seeds from multiple plants in Iceland (where most were rather bitter, but thankfully a few were not). And over the winter I requested and received seeds from two populations maintained by the USDA (one from the former USSR and one from Alaska, where canning Goose Tongue greens is not unheard of), and two more from friends.

This plant seems to have great potential as a perennial vegetable. It’s cold-hardy, salt-tolerant, and drought-resistant, with a history of being grown successfully in gardens. Its thick, succulent leaves keep well long after harvest, even without refrigeration. It’s also nutritious and delicious. And if domestication into a viable crop proves successful, it will follow in the tradition of other seaside wild plants that early farmers turned into crops, including Asparagus maritimus (the wild progenitor of asparagus), Brassica oleracea (the wild progenitor of cabbage, kale, broccoli, etc), and Beta maritima (the wild progenitor of beets and chard). The photos attached show just a fraction of the diversity I’ve found so far both in the wild populations and in the seedlings I started this spring — and wide diversity means great potential for breeding and selection to yield impressive results.

Over the coming years, I plan to make seeds from the best plants available to other growers, researchers, and plant breeders, and to collaborate on this long-term project with anyone else interested in collaborating with me — because I’m under no illusion that I alone will be able to turn Goose Tongue (or any other wild plant) into a new staple crop.

If we’re to survive what’s coming, we all need to work together.

Cooperative Gardens Commission: A Plot to Save the World

By Mary K Johnson, Hayden Kesterson, Nick P Wrenn

The Cooperative Garden Commission (CGC) was founded in 2020 to help people grow food for themselves and their communities. As many recognized at the beginning of the pandemic, the “new” hardships that many face are furthered, and in some cases even the result of, the inequality, marginalization, and exploitation endemic to our political and economic systems. The goal of CGC is to empower people to provide for themselves and each other in the face of the ongoing violence wrought by the settler-colonial, capitalist state. Seeing precedence in the individual and community response of the “Victory Garden” movement in the US during WWI and WWII, Experimental Farm Network posted a call to start a version of the movement for this time. Hundreds of gardeners, activists, and concerned citizens piled into organizing calls and working documents with the aim of putting seeds and knowledge of how to grow them into the hands of as many people as possible.

CGC makes space for learning on multiple levels, including processes of decolonization throughout our work. For this reason, as a group, we chose to not include “Victory Gardens” in the name of the organization. Though the Victory Gardens effort was extremely successful in supplementing localized food needs, in WWII the campaign was a necessity following the internment of Japanese American fruit and vegetable farmers, which reduced our domestic food supply significantly. Our hope is to recover the successful spirit of collective cooperative survival from that era, and subsequent mass mutual aid efforts, to move forward into a better future for all.

Since the spring of 2020, we have established a yearly seed distribution to hundreds of individuals and organizations across the US, who apply to become “seed hubs” in their communities, and a web of active commissioners who meet online as part of various working groups.

Such a large, grassroots effort has opened up a common space for volunteers and commissioners to learn together, addressing struggles across space and scale. This “commons,” of a sort, is grounded in the distribution of seeds, allowing our online discussions of growing practices and community engagement to have a material dimension that online organizing often lacks. The seeds themselves are donated by seed companies, thus more of a gift than a commonly held asset. In pairing them with information on seed saving and food growing more generally, we hope to adapt to rapidly changing seasons and circumstances together.

To us, getting gardens planted is an avenue of climate action and resistance to dominant power structures. Many changes must be made in order to transcend the multiple crises humanity is facing. No one approach can solve the massive problems in our global society, however, food plays a central role in nearly all of these issues. This is where CGC has some agency. Seed Hubs distribute seeds to gardeners growing in containers on balconies, community gardens, front and back yards, and other shared growing spaces across the country. The seed provided is non-GMO, unpatented, not sprayed with toxic chemicals, and represents a diversity of crops. Seed of this quality is an incredibly important tool allowing for adaptation to changing climate. Additionally, it is seed of this sort that is under extreme threat of extinction due to modern agricultural practice and policy. By distributing and advocating the use of these seeds CGC helps to preserve this invaluable resource and the knowledge of how to steward it.

There are other additional ways that these seeds affect the climate crisis. Many of the gardens where CGC seeds are sown support increased biodiversity. A garden is not the peak of possible biodiversity by definition; however, a garden can easily provide more biodiversity than a monoculture lawn or empty lot. As more food is grown locally there is a decrease in the demand for food from the grocery store which is largely produced and transported with extractive inputs. Local, chemical-free gardens provide food that is healthier for all who consume it, and healthier for the environment where it is grown. Quality seeds and empowered gardeners are a critical part of our work to grow food security and food sovereignty.

CGC is horizontally structured and focused on fostering food stability through learning and experimenting together. Every part of the work is a collaboration, from meeting notes, to statements of purpose, to grant applications. There is no cost for receiving seeds from CGC nor is there any cost to access any of our resources, assembled or created. It’s all hands on deck to grow as much food as possible in all localities. CGC aims to provide all possible resources that a community may need to take part in this task and a common forum to learn, troubleshoot, and celebrate our way through the climate crisis together.

About the Author

Daniela Soleri ethnoecologist and a research scientist at University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research is eclectic but always investigates the significance of epistemic justice in food systems research, especially focused on how practitioner knowledge affects seed systems, crop diversity and use, and opportunities for respectful partnerships between practitioners and scientists. She co-authored a recent book, Food Gardens for a Changing World.

Rebecca Newburn is the Co-Founder of Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library and created a seed library template that has helped hundreds of seed libraries launch around the world. She is the webmaster for SeedLibraries.net and the editor of Cool Beans! Seed Libraries Newsletter.

Nate Kleinman is an organic seed farmer, researcher, and activist/organizer. In 2013, he co-founded the Experimental Farm Network, which he still co-directs, and he also serves as Seed Operations Director for Ujamaa Cooperative Farming Alliance.

Mary K Johnson joined Cooperative Gardens Commission in April of 2020 with the Media Working Group first, bringing a 20+ year background in marketing and design, based in Shoshone Bannock land, Boise,ID. She participates remotely, working together with, and learning from the many volunteers who collectively created and continue this work.

Hayden Kesterson is a landscape gardener and activist on the Lenape land currently known as Philadelphia.

Nick joined Coop Gardens in February of 2022 with hopes to get more involved in efforts supporting food sovereignty and equal access to diverse seeds. Since joining Coop Gardens Nick has worked with the climate adaptations and education working groups which aim to continually improve education resources and discuss various ways that soil health plays a role in achieving the collective goals of the commission.