We are the disenfranchised people: activists, experts of our environments and the ‘local communities’ often cited in climate action agendas. We, referred to here as the Global Majority, address this to our counterparts from governments, civil society and other groups that have historically forced upon us a world order that positions a (Global) Minority as progressively superior. We speak specifically to groups working on projects that directly or indirectly affect the global majority, whether in open data, environmentalism or those at the intersections of both.

Mainstream approaches and narratives on the climate crisis still fall short of addressing core issues of justice, power and inequality. New evidence shows us that the richest people around the world are driving global warming. Most of the richest people are still concentrated in the Global Minority whilst the most vulnerable are concentrated in the Global Majority. Although these vulnerable people contribute the least to the climate crisis, they bear the brunt of climate change.

This is especially true for rural communities that live in climate-vulnerable geographies and are still reliant on the natural environments for their livelihoods. Many such communities are concentrated in the Global Majority and are made most vulnerable by their socio-economic status and low capacity to cope with climate change risk. These groups of people are also disproportionately impacted by the measures taken by international entities and governments actively addressing climate change. Their agency is often disregarded and their approaches, although proven to be the most sustainable, tokenized.

Our submission for Branch targets actors who are part of the Global Minority, recognizing that framing around the climate crisis that lacks this power analysis impacts the solutions proposed for the climate crisis. It also highlights that although an urgent matter, climate action also requires slow thought through sustainable approaches and responses.

Although an urgent matter, climate action also requires slow thought through sustainable approaches and responses.

Opening up data is an important first step in respecting the agency of marginalized and vulnerable communities and breaking the current cycle of dependency. We also believe opening up data may allow other communities to find innovative ways to tackle climate change, which is currently limited due to agenda-setting emanating from those in the Global Minority. Open climate data is a tool that can be useful for local communities, among other beneficiaries, it can assist them in drafting strong proposals for financing and developing fitting solutions that may not be apparent at first sight.

Very often these [vulnerable] communities remain solely a source of data and rarely users of it.

However, very often these communities remain solely a source of data and rarely users of it. Additionally, the reluctance of actors to open and share their data inhibits local communities from realizing the full potential of this data, such as allowing them to recognize the intersectional issues impacting them.

Data sharing also facilitates collaboration among marginalized communities—allowing them to see and identify with each others’ similar experiences and surface opportunities to combine efforts. Consequently, we have those communities who form part of the formal structures of approaches identified to help people adapt to the effects of climate change (for example such as those who are part of Community-based Natural Resources Management programs) still being unfairly disadvantaged in their capacity to respond.

Beyond accessing climate finance for adaptation and mitigation, vulnerable communities and countries should be compensated for loss and damage by the Global Minority who have contributed to and benefited most from the climate crisis. Further to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) scope on loss and damage we support the sentiments of a report by the climate and community project stating that, “Climate justice should not be thought of simply as compensation for past environmental, economic, and social damages, but as world making—that is, debt justice and enhanced climate finance should help build a platform for countries in the Global South to achieve low-carbon development and robust, resilient infrastructure.”

We link this to current climate action approaches which ignore the historical accountability of the Global Minority and the unequal distribution of the benefits of climate data, specifically open climate data.

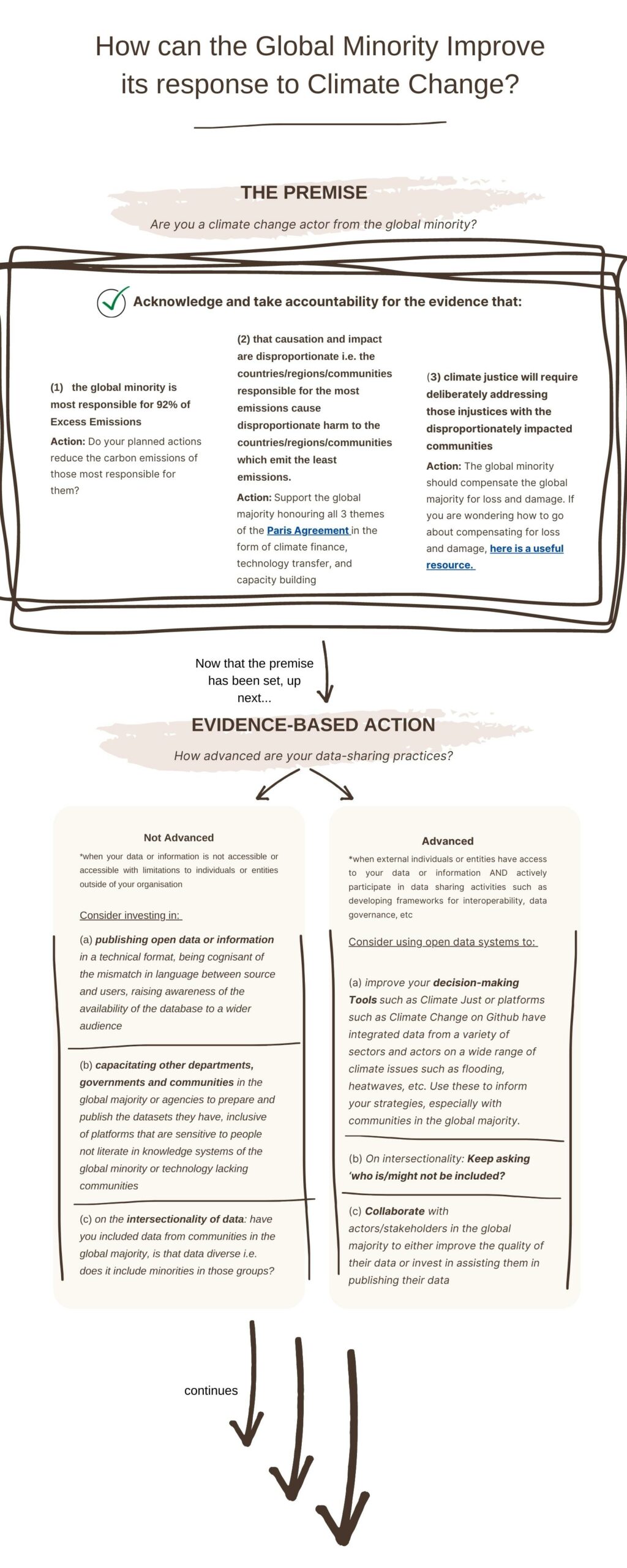

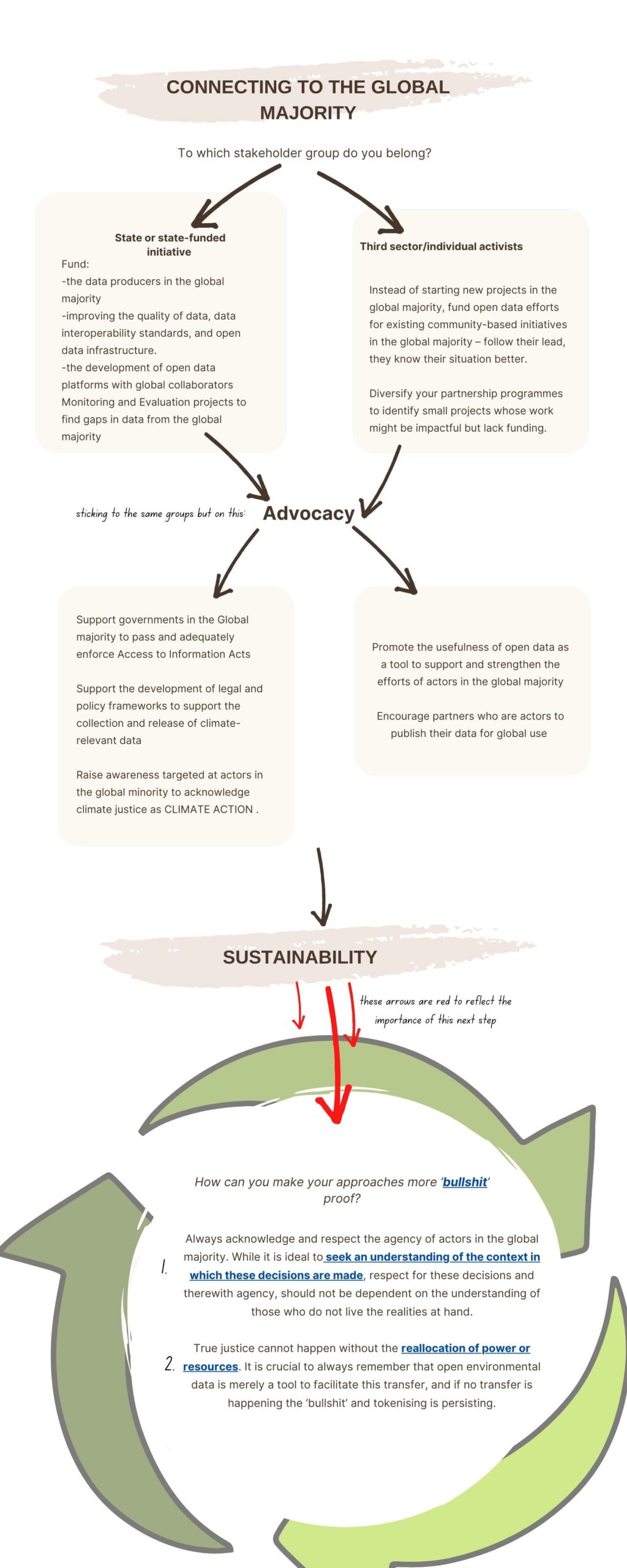

The downloadable graphic below applies a justice approach to climate action first by recognizing that not all actors carry the same responsibility when it comes to climate change action and secondly, that global experts need to be explicit in their recognition of local communities as agents of their own situations.

**There are key links in blue in this image that we encourage you to click through. To access them, please download the pdf

About the Authors

Brisetha Hendricks is a community leader and social justice advocate. She is also a communications student with a particular interest in political communication. She has extensive experience in community-based natural resource management and climate change impact amelioration projects. She currently serves as chairperson of the Southern Kunene Regional Conservancy Association in the rural northwest of Namibia.

Kristophina Shilongo is a policy researcher with interests in applying a social justice approach for the sustainable adoption of data-driven technologies. She is also curious about drawing lessons from the management of other resources to apply to collective/participatory data governance frameworks.