The web holds the promise of connecting people across distance and difference. A browser is a tool designed to make these connections possible by accessing and rendering websites. Yet, reimagining what browsers could or should be is difficult because we are so used to the familiar patterns of tabbed interfaces and ad-driven design that defines most browsers today.

In this article, we ask afresh: What if the browser were more attuned to the natural world? What if it responded to the ebb and flow of natural systems and operated more thoughtfully with the limited planetary resources available? What could browsing the green web look like, and how could we even get there?

For the last 15+ years, we’ve worked on topics related to the open web, including in collaboration with major browser makers. Responding to this issue’s theme, we wanted to survey the current browser landscape, its possibilities and constraints, and see what threads might be interesting to follow. Come along this exploration of what sustainable browsing could look like!

Browsers today

The major browsers of today are controlled by a handful of companies, each defending their financial strategic interests in the space. Browser engines, the underlying software implementations of the web itself, are very large and complex. The cost of making a new browser engine is therefore quite high – requiring millions of dollars in funding and a team of specialized engineers just to get started.

For a long time, this combination of size, complexity, and cost made it very difficult to change web browsing. It also created a higher barrier to entry for newcomers, narrowing our imagination about what a web browser can be. While the web itself is still not easy to change, the maturity and stability of open source web engines has made a blossoming of new browsers possible, some with fresh propositions around security, privacy, or productivity.

Some new browsers are designed to do very specific things well, such as Wavebox‘s focus on workplace productivity, or Polypane which is specifically aimed at web developers. Others want to be all-arounders, such as The Browser Company’s Arc and Dia products, Kagi’s Orion browsers, and a new Firefox-based browser named Zen which is growing in popularity for its customizability. In this landscape, Ladybird is unique: A non-profit group is attempting to build an entirely new web engine and browser from scratch, likely a decade-long project.

Meanwhile, we are seeing the energy sector become more like the web. Real-time data about the electricity grid, such as its carbon intensity, is becoming more accessible and actionable. That means you can connect information about the current electricity grid with your browsing experience, as the Green Web Foundation’s Grid-aware Websites project demonstrates. What’s more, there’s growing interest in routing internet traffic along the greenest pathways, optimizing packet flows for energy efficiency, and prioritizing websites that are running on 100% renewable energy or other verified green energy claims.

These conversations are happening within a larger political context of massive investments for ‘AI gigafactories’ and similar megaprojects. The investments are often conducted under the guise of energy efficiency and future climate gains. However, we should assess these promises with a wary eye, especially since the rebound effect proves time and time again that gains in efficiency result in more usage of a technology, rather than less.

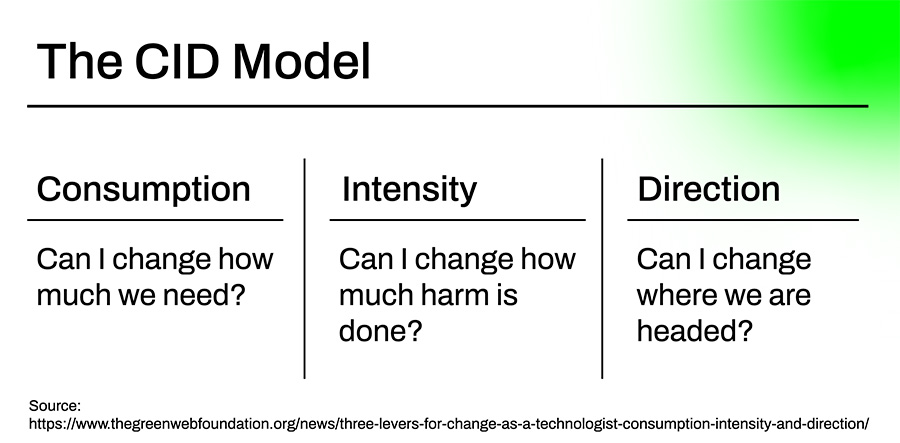

The model of Consumption, Intensity, and Direction created by Chris Adams at the Green Web Foundation helps us pinpoint the kind of change we’re working towards. Is it about reducing how much is consumed? Is it reducing the harm that’s caused? Or is it changing the (structural) direction we’re headed in? The ideas in this article respond in varying degrees to these questions.

1. Consumption

When thinking about how to green the web, the first instinct is often to focus on reducing consumption. This section explores how making consumption visible can serve as a lever for change, how browser functionality might be extended to support this awareness, and how adopting a ‘local-first’ approach could reduce the need for intensive computational resources.

Dimensions of observability on the web

To build a greener web, we must first be able see the web as it exists today. The web is not a single static entity but a dynamic ecosystem made up of browsers and web standards, publishing pipelines, content aggregators, advertising networks, backend databases, and the JavaScript libraries that ship with the pages and the servers that host them, the ‘series of tubes’ that carry it all, and so much more.

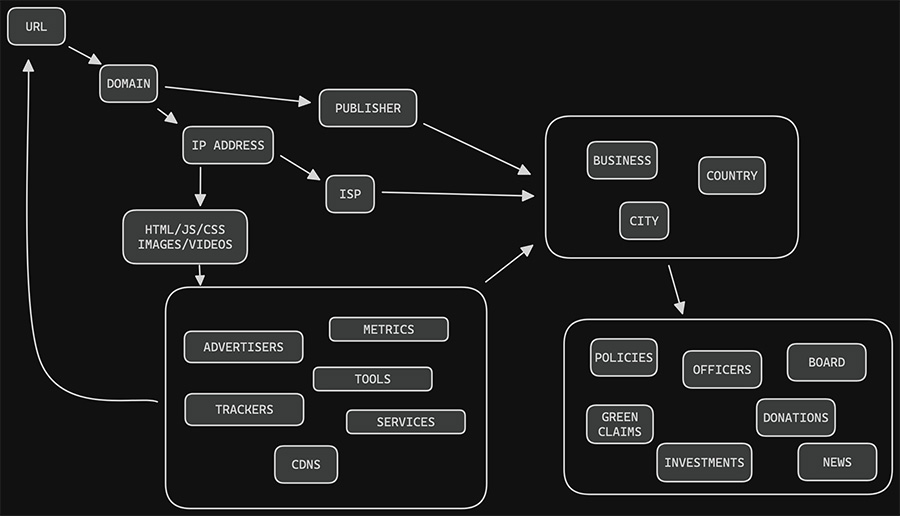

Loading a web page is an incredibly complicated and multidimensional event, spanning the globe and often involving thousands of companies, a huge amount of data, and an incomprehensible maze of network connections – any of it may be a signal of direct or indirect energy use, energy policies and more.

When you enter a URL, the browser first queries the Domain Name System (DNS) to resolve it into an IP address, then sends a request to that address to retrieve the website’s content. That IP address is registered to an Internet Service Provider (ISP), whose corporate identity – name, headquarters, and public records – is publicly available.

Domain names are registered in public databases which typically contain information about the business behind them. While this data can be obfuscated, the actual publisher’s business details are frequently disclosed, and increasingly required by law for many kinds of websites.

We can analyze the path the request took, and see if any content delivery networks (CDNs) were used, and if any pages, scripts, images and videos were loaded from other websites (more companies!). We can also learn how the page itself was authored, and what services and tools were used – the content management system (CMS), JavaScript and CSS frameworks, any metrics or reliability services, and even ecommerce platforms like Shopify.

In 2024, Wired reported that some popular websites share data with over 1,500 partners. Not all of those are loaded directly into the website, but many often are.

Within that burst of network activity and the content it returns lies a wealth of other information about the business behind each piece: sustainability claims, published policies, political donations, news coverage, even controversial customers. A single lookup offers a revealing glimpse into the broader environmental, ethical, and social context behind any website.

Projects like Firefox Lightbeam, originally developed by Atul Varma at Mozilla, pull back the curtain on the thicket of third-party trackers following us invisibly throughout the web and how they collude with one another to share data about what we click on and where we go online. Tools like Are My Third Parties Green?, developed by Fershad Irani at the Green Web Foundation, help illustrate these dependencies and how changing vendors may result in an improvement in the energy consumption or carbon intensity of a website.

Extending today’s browsers

We’ve focused on the companies and industries behind websites, and the ways in which they make, serve, and distribute content. These are indirect costs to you – side effects of loading a particular website. But there are also direct costs. Inefficient web code runs on your device, which you keep charged.

Could we build a browser extension that shares that information with you as you browse? Then you could make decisions about which websites to visit, based on how much energy they make you use.

Browser extensions often fill the gap between what a user may need and what a browser maker probably won’t implement. These are small software programs that access browser internals to add features that may not be for everyone, but are still useful. Some explorations for using extensions to greening the web include:

- Themes: A theme modifies the colors and visual styles of the browser. What if a theme changes color based on the green web rating of the visible website?

- Filtering network requests: Ad blocking is the most common use case here. What if you could identify assets loading from known carbon-wasteful domains and block or replace them? Maybe the websites would not function as well, but you could have a “ok, use this wasteful website” button or other interaction to bring attention to it. (“Ad blocking is climate action!”)

- CO2.js on every page: The Green Web Foundation’s CO2.js project is an open-source JavaScript library, which websites can include to understand their energy usage. You can also see the output in the Firefox Profiler. This is opt-in by websites… but browser extensions let you include scripts in pages. Can we make an extension that adds CO2.js to all the pages you browse? Also, the Firefox Profiler is not a user-friendly tool (it’s even confusing for developers!), so perhaps we could provide simplified decisions for end users to take action while we run it?

Firefox itself does have energy consumption APIs internally but they’re not available to websites or browser extensions. Unfortunately, browsers have been steadily restricting the capabilities of extensions for years. In particular, Google unilaterally added controversial limitations to what extensions can do in its shift to ‘Manifest v3’ .

Browser extensions are not considered part of the web, so those capabilities aren’t governed by the W3C (though there’s some coordination now, a good sign). Extensions are also not the default user experience, and therefore only a subset of web users will ever install them. While we can get pretty creative by extending the browser, they’re not an avenue for direct and structural long-term change.

Energy and data locality: CDNs, P2P, and AI

Movement is intrinsic to networks. The web moves across the internet. People request web pages. Servers respond. Each of these exchanges is an explicit instruction to move data, resulting in a continuous flow between many points.

Data movement has a cost – transmission networks use around 250 TWh each year according to the IEA. But, because of the distributed nature of the internet and how routing decisions are made today with BGP, we have limited control over which networks our packets use in transit.

Meanwhile, renewable energy is increasingly the cheapest power available, albeit a variable one. If you want to use greener network infrastructure, your packets should respond to the conditions on the grid. That means avoiding times and regions where electricity mostly comes from burning fossil fuels.

Does reducing ‘distance’ reduce overall energy use? Let’s look at some architectural approaches to the locality of data on the web.

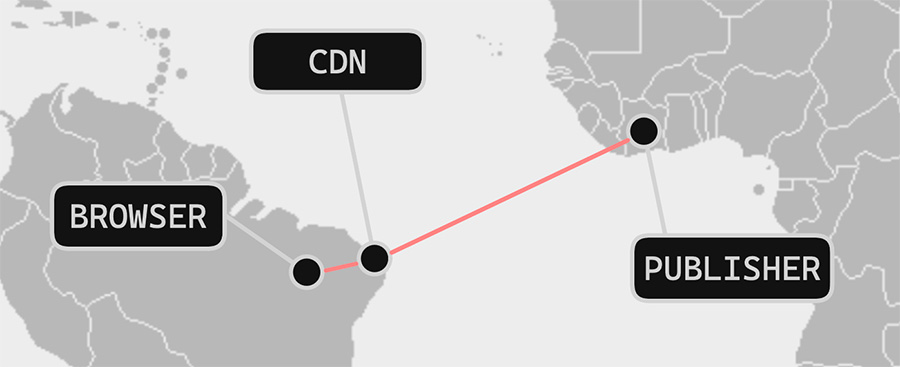

CDNs

CDNs are companies that reduce the distance data needs to travel, resulting in a better user experience and lower costs for publishers. CDNs maintain points of presence (POPs) in different geographic areas, and publishers pay the CDNs to service regional requests for content from the closest POP, reducing the amount of content making the full trip from the publisher’s server.

Do publishers not using CDNs consume more energy? What’s the energy usage of the data center a given POP runs in? What if the upstream publisher uses a data center primarily powered from hydroelectricity, while the POP data center is powered by local coal energy? Or vice versa?

CDNs can see patterns across large swaths of web traffic. Perhaps that’s an opportunity to shape traffic at scale on the internet. If CDN usage is generally more efficient, what if there were tax breaks for publishers who use CDNs or regulation incentivizing their usage?

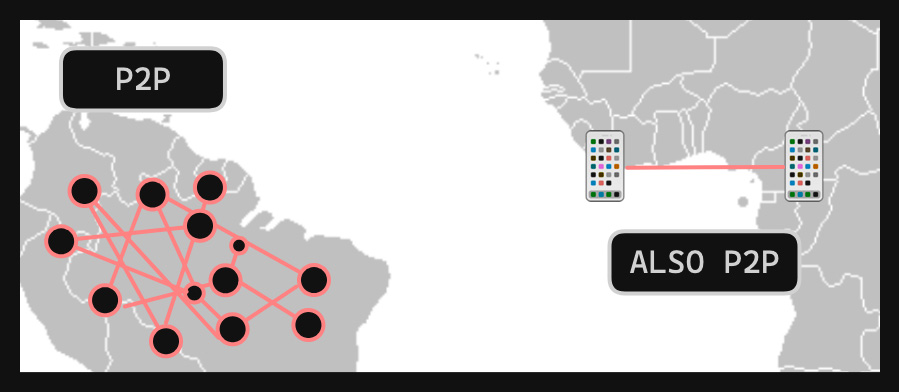

P2P

Are there different ways we can move data that may be more efficient or sustainable? Are there ways to radically reduce data movement?

Peer-to-peer (P2P) technologies are not new, but must be re-examined from a sustainability perspective. In P2P web approaches, the client and server lines blur – browsers can also be servers. Often, these networks are composed of users’ own computers rather than being operated by a single company running centralized servers. P2P can also refer to direct connections between individuals, such as Apple’s Airdrop, or to devices communicating over a local network, like in your home.

The experimental P2P browser Beaker would publish your website locally in the browser and make it available to other Beaker users over a P2P network. BitTorrent, the protocol infamous for file-sharing in the 2000s, also started developing a Chromium-based browser. Brave has been supporting IPFS (Interplanetary File System) for a few years already, the most recent major attempt at a P2P web browser.

While none of these options is around today, each offered a way for users to publish and read together over local networks instead of having to go to a remote server. Further research is needed to understand the energy usage patterns of this approach.

A related pattern is ‘local first’ computing. Coined by Ink & Switch in 2019, local-first software is designed to work locally, without a server component as a requirement. If you want to collaborate with others, you can layer that on, but the core architecture doesn’t care if that component is HTTP, P2P, or carrier pigeon. While there are no browsers for the local-first web yet, Peter van Hardenberg of Ink & Switch made TrailRunner, which lets you load local data into traditional web applications.

P2P and local-first reimagine the traditional idea of ‘servers’, either removing them entirely or turning all users into hyperlocal servers. How do they stack up from a green web perspective?

Some P2P networks move web content around in tiny pieces, each served redundantly from many nodes in the network. A simple request for an image in a page might be handled by hundreds or even thousands of computers. Does this use more or less energy than a single-company product running in a data center? The trade-off for resilience could be worth the higher carbon cost in critical situations, but without visibility into that cost, it’s not possible to evaluate. Modeling these costs could be an interesting avenue of research.

Additionally, the ability of a network to scale both up or down could be interesting from an energy consumption angle. Similarly to the CDN example, P2P networks can efficiently scale up to large numbers of readers when data can be served from the ‘closest’ nodes instead of crossing oceans. P2P networks can also scale down. If you’re only sharing data with the group of people in the same room, no data need to leave the physical premises.

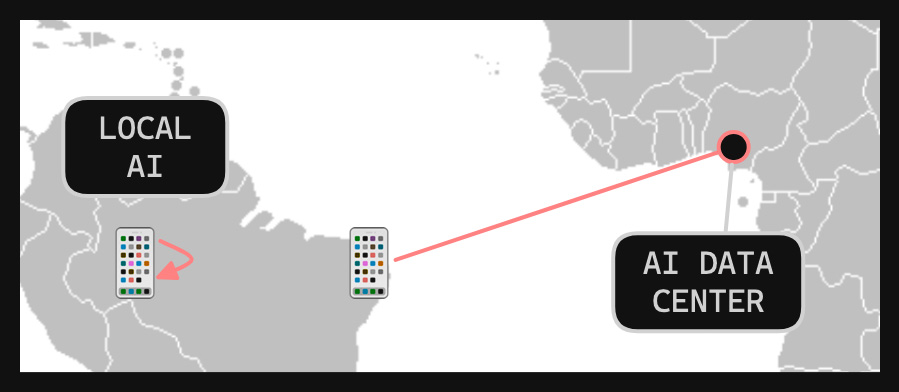

AI

AI is a hot topic and can be very energy-intensive (see the joint statement we helped author on keeping AI within planetary boundaries). A big driver of this energy consumption is the training and usage (inference) of large language models such as ChatGPT. This form of generative AI is locking in reliance on fossil fuels, projected to require unprecedented amounts of energy, and delaying climate action.

Rather than using highly centralized and resource-intensive AI, looking at it through a locality lens prompts (pun intended!) interesting questions.

We’ve discussed network traffic volume and how fewer requests may use less energy. If a remote LLM has already processed vast amounts of web data, does asking it a question – despite it running in a data center – result in a net decrease in energy use compared to individuals spending hours making redundant web requests, causing multiple servers to do more work for relatively little research output?

What about offline local models? If you can download a model once that can answer basic questions, would consumer AI traffic be meaningfully reduced? What about training models locally as you browse… perhaps that would create less network traffic for a model that’s less powerful but more personalized and also private?

If every consumer is running models locally, are we just spreading the load? Is that a new and even broader inefficiency? How does the energy cost of a billion micro-models compare to one mega-model servicing a billion users from a few data centers? What might the tradeoffs be, not just in terms of efficiency, but also in challenging market concentration among cloud providers and disrupting the imperative to adopt or die with AI?

How is this playing out in the browser landscape? Today’s three main browser engines are going in very different directions with AI. Mozilla is putting AI in the browser but not the web. Google is bringing AI as close to the web as possible. And Apple is looking at integrating AI at the OS level.

We’re seeing new AI browsers and other AI web products and services pop up nearly every day now. It would be welcome to see more development that embraces sufficiency principles and prioritizes frugality and locality over brute force and overconsumption.

2. Intensity

In the CID model, examining changing intensity means asking whether it’s possible to reduce the harm being caused. For example, fossil fuels are known to produce significant harm. Their carbon intensity reflects the widespread, systemic, and often diffuse impact they have by contributing to climate change.

But intensity can also be understood in more localized terms – referring to the damage done at the sites where fossil fuels are extracted, refined and burned. In this context, intensity describes the amount of harmful particles released per unit of energy produced.

Web standards

The world of web standards also provides some interesting threads to explore. These standards represent agreements among browser makers on what to implement, though enforcement is limited – largely relying on market dynamics and voluntary adoption. The major browser vendors dominate these standards bodies, and if the main browsers don’t support a standard, it rarely gains meaningful real-world traction.

Notably, the W3C included sustainability in its Ethical Web Principles, which serves as a guiding framework for the web community. Since last year, the W3C has convened a Sustainable Web Interest Group, which includes invited experts from the Green Web Foundation, to develop and document best practices addressing sustainability in digital technology and its effects on people and the planet. Web sustainability in the W3C context is defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” and encompasses not only the protection of environmental ecosystems and people, but also grounding practices in equity.

Complementary efforts are underway to verify (in webby ways) facts and news. How can a claim be made that an image is bonafide or a deep fake? Or that a news story is undoctored? The BBC made a splash when it produced a metadata-proven story that uses an emerging standard for verifiability in journalism on the web called C2PA to provide credentials for its content. Relatedly, the Authentic Web workshop series at the W3C seeks to shift the web to more trustworthy content without increasing censorship or social division.

These patterns of verifiability could be relevant when we think about green energy claims. For example, if a provider claims it runs on 100% renewable energy, how can this be backed up? It’s becoming increasingly possible to demonstrate how a given hour of usage in a data center is matched with 100% renewable energy that is generated locally and additive to the local grid. These claims help to make the case that fossil fuels were actually displaced, rather than burned and ‘offset’ in a broken scheme. As the demand for more rigorous evidence of green energy increases, there may be things to learn from how the web community is proposing to support verifiable claims around identity and authentication.

Attunement: the green web tools of tomorrow

Alongside changing browsers and web standards, what are other things that could be done to build the green web tools of tomorrow?

Riffing on Branch’s theme of attunement for this issue, we might begin with rethinking web applications. Rather than loading a huge program, what if the right-sized computation was used for the task?

A ‘web workbench’ is one way we might achieve this right-sized approach. Imagine breaking the browser into smaller parts so that, instead of running a complex, all-purpose program, you launch the exact tool needed for each task. For example, opening a URL that exists for just one visit. We could play with the temporality and ephemerality of a webpage.

Weightless, junk-free websites that do one thing well, without the bloat of, say, purchasing a single book on Amazon, which artist Joana Moll so beautifully critiqued with its “1,307 different requests to all sort of scripts and documents, totaling 8,724 A4 pages worth of printed code, adding up to 87.33MB of information” and an estimated 30 wh of energy to load all the web interfaces.

Tab hoarding is a common malady for many using the web today – an example of the largesse of the one-size-fits-all consumer experience. The browser business model is designed around ‘more’, so this is not considered as a problem to be solved. Task-aligned browsing or user-defined user agents are ways we could describe this kind of ‘right-sized’ browsing experience. Despite these seemingly intractable challenges, new browsers are emerging – a signal that the door may be finally opening for more innovation in the space.

3. Direction

In the third part of the CID model, we consider changing direction. This approach is not just about reducing the rapid consumption of the planet’s finite resources and minimizing the intensity of harm. It’s also about challenging the overinvestment in and unchecked expansion of digital infrastructure – especially when it reinforces extractive practices. Here, the focus is on how we might redirect investment and technical experimentation in more equitable and sustainable directions.

Actionability

In the observability section, we learned that there’s a lot of data in several different dimensions, each which tell different stories about sustainability and energy use.

With all this information comes another kind of challenge: helping people understand it and take action. There are patterns again we can learn from other web topics. In digital security, browsers established the closed padlock as a symbol that a webpage has a secure connection. What basic literacy might we expect people to have or learn to enable greener browsing experiences? What behaviors might be cultivated to shape browsing practices in more sustainable and empowered ways, while at the same time not placing responsibility for these structural harms on the shoulders of everyday web users?

Relatedly, how might visualizations help us understand the complex supply chains behind loading a single website? Vladan Joler and Kate Crawford’s Anatomy of AI provides a super-exploded view of the human and ecological ties behind a single Amazon Echo. Perhaps similar explainers can show the full social and ecological cost of a web browsing session, and better still, guide us to understand where we can intervene in these systems, rather than feel like we have to become internet monks.

New literacy can lead to new behaviors. A challenge will be to direct this beyond personal guilt or paralysis and towards effective structural change.

Glimpses of a greener web

The web is shaped by daily use, corporate interests, principled interventions, and collective imagination. It’s a negotiation between how people interact with it, how technology companies profit from it, how standards bodies and NGOs work to uphold public values, and how we envision what being online means.

The web of today must operate within planetary limits. Some paths forward are becoming clear: phasing out fossil fuels in data centers, reducing absolute emissions across the web’s entire supply chain, and ensuring that people have a meaningful role in shaping the digital futures they want.

Many of the ideas in this article don’t address the structural changes needed to build more equitable and regenerative digital systems. (For recommendations along those lines, check out the Green Screen Coalition and its inspiring network of digital rights and climate justice organizations). Some of the suggestions here may not be particularly effective, profitable, or even feasible. These are systems of endless and compound complexity, and there are no simple solutions – but there are promising threads worth following.

We’re looking forward to the explorations and experiments ahead – be they browsers, standards, or entirely new approaches – that help create the just and sustainable web of the future.

Dietrich Ayala has been working on browsers and the web at organizations like Mozilla and Protocol Labs for nearly 20 years. He is currently exploring what the web can be when the browser is left behind.

Michelle Thorne is the Director of Strategy at the Green Web Foundation, co-initiator of the Green Screen Coalition for digital rights and climate justice, and editor of Branch magazine. She’s curious about reconnecting with the radical roots of openness and caring for the commons.