We are at a critical threshold in our computational future. Rapid expansion of data centers, semiconductor manufacturing, and fossil fuel usage are all booming in response to unprecedented private and public investment in digital infrastructure. In 2024, the 1.5°C global warming limit was surpassed across the entire year, and the boundaries of several life-supporting planetary systems have been exceeded. More intense heat waves, storms, fires, and floods remind us of how human activity impacts all life on this planet.

Much of the internet today is part of larger, extractive systems that are exhausting critical resources like water, land, and raw materials – intensifying environmental harm across the technology supply chain and increasing greenhouse gas emissions, which heat up the planet and concentrate wealth in the hands of a few.

Is a different way possible?

What if we rebuild the internet to respond better to the constraints of the energy grid? How could we adapt the browsing experience to use fewer resources when fossil fuels are being burned and support awareness of how the physical realities of the planet affect our experience on the web?

What if we reimagine digital infrastructures attuned to life systems? Digital futures that are built by default to operate within planetary constraints? What if we could prioritize community ownership of the internet, joy, and just the right amount of technology to meet collective needs?

This issue of Branch sets out to play with these possibilities through the lens of Grid-aware Websites. Together we’ll explore what’s possible right now and where we can take things through the collective imaginings of future pathways. We’ll also touch on ideas such as tiny infrastructures, regenerativity, and other alternative approaches to bring our browsing experiences more in touch with the natural world and the more-than-human lives all around us.

Editors Q&A: What’s in this issue #9?

Read more from our editors about the articles in this issue and why we’re excited for readers to dig in and become attuned.

Michelle Thorne:

Fershad, you edited a couple of sections of this issue of Branch. Can you tell us about the articles that are featured in it?

Fershad Irani:

Sure! I edited the sections on Attuning the Web and Building a Grid-Aware Web. A lot of the articles in this section build on the Grid-aware Websites project we’ve been working on over the last year, where we’ve been developing a toolkit for developers and designers to create dynamic web experiences that respond to the carbon intensity of the energy grid.

As part of that project, we brought together a wonderful advisory group, made up of community members from CMS projects and independent specialists. Several of them have written articles for this issue. One strong message that came from the group was the importance of making the business case for sustainable design – how to speak about these ideas in a way that resonates with decision-makers.

We begin the issue with Nick Lewis and Lucy Sloss, both members of the advisory group, who offer a forward-looking perspective to a future where the physical world and the internet are truly attuned. It’s a thoughtful introduction to the larger themes of this issue.

From there, we dive into the grid-aware web. Tom Jarrett shares the story of how we redesigned the Branch site itself to better reflect real-time energy data. Then Michael Oghia, together with Andy Eva-Dale and James Hobbs, offers practical guidance on how to communicate the value of grid-aware websites to organizations – an important resource for advocates inside institutions.

Grace Everts presents fascinating user research from Harvey Mudd College, where she studied how people react to the environmental impact of browsing once they’re made aware of it. Hopefully, it prompts others to continue with similar research projects. Grace’s findings set the stage for Raj Banerjee and Shraddha Pawar, who offer a design pattern that gives users the ability to pause features when the grid is dirty. It’s a small but powerful form of agency and a nicely nuanced take on the idea of grid-aware websites.

Tia Nguyen then contributes a thoughtful piece on how digital sustainability can be brought into the everyday workflow of developers through a Visual Studio Code extension.

Michelle:

There’s also Nora Ferreirós and Nauhai Badiola who have been working on some examples in WordPress. Could you share more about what’s going on in the world of WordPress and grid-awareness?

Fershad:

Yes, absolutely! A very large portion of the web runs on WordPress, and Nora and Nahuai have been thinking about how the Grid-aware Websites project can be built to work with those sites. WordPress has a really nice plugin ecosystem which allows any user to add specific bits of functionality to their site (forms, image optimization, etc.) with just a few clicks.

So Nora and Nahuai haven’t just written an article for Branch (in both English and Spanish!), they have started work on a Grid-aware Websites plugin for WordPress as well. Their article looks at some of the features the plugin aims to introduce to the WordPress editor, and how WordPress authors can control the changes the plugin makes to their website. It’s great to see an idea like this come to fruition, and I know there are members of the WordPress community who are excited about it as well!

Michelle:

That’s fantastic – yes, the Branch site itself runs on WordPress, and as part of this issue, we’ve done a lot of updating to the code. There’s going to be a new and improved way of seeing grid intensity information on Branch.

Fershad, you’ve been working closely with designer Tom Jarrett on how to make the energy grid more visible through design. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Fershad:

Definitely. When we started the Grid-aware Websites project, we saw Branch as a really good opportunity to “dogfood” our toolkit and explore grid-aware patterns in a live setting. Tom, who designed the original Branch site in 2020, returned to collaborate with us on this new iteration.

We focused on how to surface grid intensity data to users – not just passively, but in a way that gives people control. This led to the development of a new web component specifically for grid-aware interfaces, which now appears at the top of the redesigned site. Tom’s article also talks about this and unpacks the design choices we made.

Michelle:

Amazing! We’re looking forward to people checking out this section of Branch focusing on the grid-aware web. Now, I’ll hand the mic over to you, Fershad.

Fershad:

Thanks! So, Michelle and Fieke – you co-edited the Regenerativity section. What does attunement mean to you in that context ?

Michelle:

To me, attunement means bringing things into harmony, and making systems more aware or responsive to life. It felt like a fitting theme for this issue.

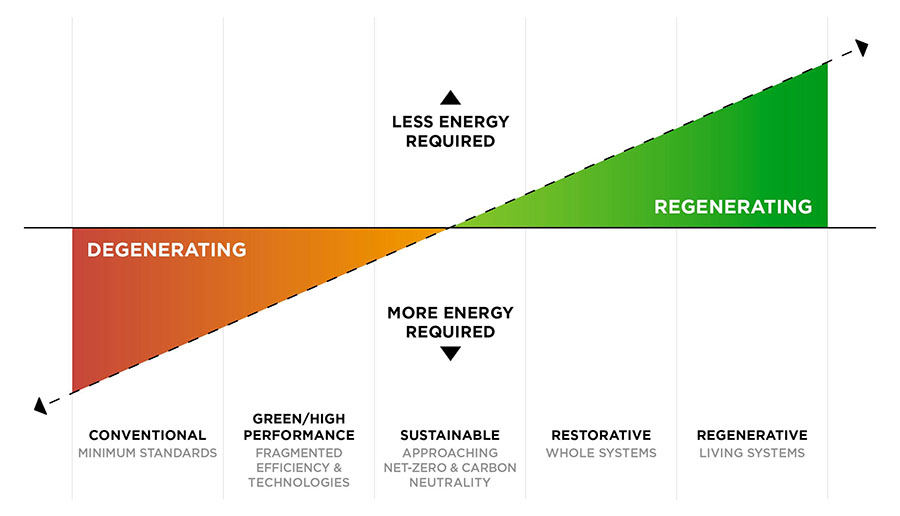

Together with the amazing Dr. Fieke Jansen from the critical infrastructure lab, we wanted to showcase a shift – not just toward more sustainable digital infrastructure, but toward more regenerative ways of thinking. That means moving past simply reducing harm to imagining systems that replenish and support life over the long term. Fieke’s brilliant article lays that out really clearly, with a helpful diagram showing the spectrum of action from sustainability to regenerativity.

We also tried to keep things playful, by asking: What would regenerative computation look like? How can responsiveness be built into systems?

Fieke Jansen:

Exactly. This section grew out of conversations that Michelle, Lori Regattieri, and I have been hosting, including a dialogue and debate series in late 2024 exploring how we can reimagine digital infrastructures to be smaller, more equitable, and rooted in community.

The event was an invitation for artists, thinkers, and public interest engineers to imagine what responsive and regenerative infrastructures look like that center people and the planet over the accumulation of capital and power through extractive logics. To co-produce knowledge on how we can build sustainable and equitable futures requires an open process, where we imagine and think out loud together. To overcome what Mark Fisher described as capitalist realism, where it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

The dialogue and debates series did just this: It brought together people from across the globe to get inspired and discuss alternative pathways forward. Some contributors to that series are featured in this issue.

Fershad:

Michelle, do you want to talk us through the other articles in this section?

Michelle:

Absolutely. We open with a piece that Dietrich Ayala and I wrote together, which explores the role of browsers today and offers provocations for how we might green them and make them more sustainable. Next is David Mahoney’s thoughtful essay on grounding us in the physical realities of data centers and (by drawing inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement in the UK) proposing a place-conscious approach to the cloud.

Ola Bonati and Judith Veenkamp contributed a wonderful piece on permacomputing, featuring a zine that explores provocative, low-tech prototypes. Their work, and that of the artists they feature in the article, help us reimagine computing through the lens of ecology.

Fieke:

The great thing about Ola and Judith’s piece is that they highlight several artists, designers, and researchers who – through their creative practices – challenge our understanding of computational progress. For example, Lukas Engelhardt questions the idea that we need bigger, faster, and better computing – with a tiny computing project. He designed a small server which runs on only 12 volts. The article also looks across these projects to identify what is needed to imagine alternative pathways: becoming a kind of scientist, taking time to explore, finding community, and allowing for complexity.

Another one of these artists is Sunjoo Lee, who wrote about her Gardening Electricity Handbook in this issue, a practical guide to mud-powered circuits. It’s not that this project generates a lot of electricity, but it helps ask the question of what it takes to power digital systems and to demonstrate that not every mud sample is the same. Some mud samples contain different compositions of life, and different organisms have different properties. There’s an attunement to place when we consider where these different mud samples have come from. So her project is quite beautiful.

Michelle:

We also have Alexis Oh, who shares a sonic project called Sounds of the Grid. It invites us to listen – not just see – the changes in grid intensity, as we browse the web.

Lori Regattieri’s article then reflects on the geopolitics of AI and climate change, especially how the Majority World is often treated as raw material for US tech companies, further concentrating private wealth. She offers some really beautiful provocations around how to redefine what innovation means if we rebalance the geopolitical relationship away from an extractive to a more equitable one.

Rounding out the section is Esther Mwema’s article Cosmology of the Internet, which presents three artworks that trace the colonial legacies, sacrifice zones, and future visions tied to today’s internet.

It’s an incredibly rich issue. Thanks for sharing your reflections, Fieke and Fershad – and to everyone who contributed. We hope readers feel invited to explore, experiment, and imagine more attuned digital futures.

Acknowledgements

This issue of Branch would not have been possible without countless hours of effort behind the scenes over the past few months.

To all the authors who have turned their thoughts and ideas into the wonderful collection of articles that make up this issue, thank you.

Those articles were masterfully copy-edited by Oliver Lindberg, who worked with all the authors and editors to refine the stories that are told in this issue in ways we hope will resonate with you.

Branch wouldn’t be what it is today without the work of Tom Jarrett, who has been a close collaborator since the beginning. For this issue, he came up with a fresh new design for the Branch site and also created illustrations for some of the articles. Also thank you to Tessa Curran, who created the cover illustration for this issue.

Finally, absolutely none of this would have been possible without the tireless coordination and planning efforts of Katrin Fritsch and Hannah Smith, who juggled all the moving pieces required to put this issue together with aplomb.

Fershad Irani is a web sustainability consultant living in Taipei, Taiwan. He works with the Green Web Foundation across a range of areas, particularly turning sustainable web ideas into working prototypes and code libraries. He specializes in carbon emissions calculations, and is the lead maintainer of the CO2.js library as well as the Grid-aware Websites project.

Fieke Jansen is a co-principal investigator of the critical infrastructure lab and a postdoc researcher at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests are to understand power and conflict around the environmental impact of expanding infrastructures. She is also the co-lead of the Green Screen Climate Justice and Digital Rights coalition.

Michelle Thorne is the Director of Strategy at the Green Web Foundation, co-initiator of the Green Screen Coalition for digital rights and climate justice, and editor of Branch magazine. She’s curious about reconnecting with the radical roots of openness and caring for the commons.